Campaign 97

Bussaco 1810

Wellington defeats Napoleons Marshals

Ren Chartrand Illustrated by Patrice Courcelle

Series editor Lee Johnson Consultant editor David G Chandler

CONTENTS

Marshal Andr Massna, Duke of Rivoli, Prince of Essling (17561817), commander of the French Army of Portugal tasked by Napoleon with the conquest of Portugal in 1810.

ORIGINS OF THE CAMPAIGN

I n the year 1810, Napoleon Bonaparte, emperor of the French, reigned supreme over much of Europe. The influence of the French emperor was felt as far away as Russia and Turkey. His direct rule extended as far as Poland and the northern Adriatic seacoast in the Balkans. The Russian empire had been humbled in 1807 and the Austrian empire had seen French troops march into Vienna in 1809. To seal the alliance with Austria, Napoleon took Princess Marie-Louise as his new empress and she would indeed bear him a son, whom the emperor immediately made the king of Rome. Thus, almost everything in western Europe swayed to Napoleons fancy.

There remained, however, one or two black spots to tarnish the gleam of Napoleonic Europe. First and foremost was Great Britain, the rich and powerful island nation that just never seemed to admit defeat in its struggle against Imperial France. Napoleon reigned over western Europe, making and unmaking kings, but Britains Royal Navy reigned supreme on the seas around Europe and, indeed, across the globe. French warships were, by and large, blockaded in various continental ports not daring to venture out; when they did, they were nearly always beaten back with loss. Napoleon had decreed the Continental Blockade of Britain in late 1806. Three and a half years later, Britons flourished and had all they needed while the remains of the French merchant fleet was in agony and French households were getting desperate for sugar.

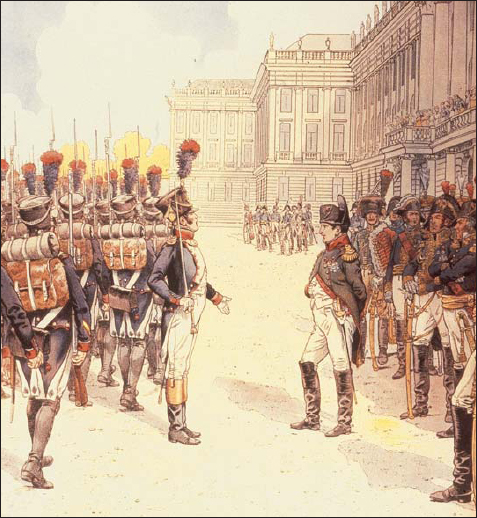

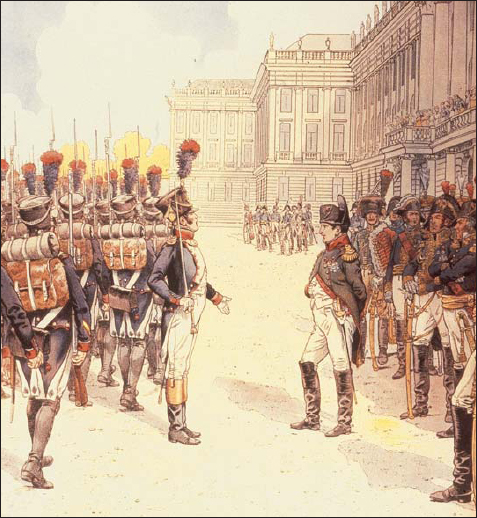

Napoleon and his staff reviewing troops at Shnbrunn Palace near Vienna in late 1809. With the defeat of the Austrian empire, Napoleons power in western and central Europe reached its zenith. Only Britain, Russia and Portugal remained unconquered by the mighty French imperial army. (Print after JOB)

Britains resilience in her struggle against Napoleon was largely due to her world-wide trade and the absolute superiority of the Royal Navy. (Print after Atkinson)

To make matters worse for Napoleon, even his mastery of western Europe was not quite complete. Despite all his attempts at conquest two areas continued to resist him. Behind both the emperor clearly saw the perfidious hand of Britannia.

The smaller and more remote of these was the island of Sicily. When the French invaded the Kingdom of Naples (also known as the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies) the British had immediately secured the island of Sicily, where the Bourbon royal family of Naples set up court at Palermo. A French attempt to drive out the British and Neapolitans had been defeated at Maida in 1806 but later British raids further north had failed with heavy losses. Sicily proved a good base for seizing the few islands occupied by the French off the Balkan Adriatic coast and for the Royal Navy to keep French and Italian warships at bay. The situation was a stalemate with little actual fighting taking place.

The other much larger problem for Napoleon was presented by the Iberian peninsula. There he had been drawn into a seemingly endless conflict. The situation in Iberia, far from improving, was getting worse. The struggle had been sparked by Napoleons attempt to take over the peninsula three years earlier. After a bloodless occupation of Portugal in late 1807, he had deposed the degenerate Spanish Bourbon royal family in early 1808 and placed his brother Joseph on the throne. The whole peninsula had erupted in May and June 1808, King Joseph having to flee Madrid while a Spanish army crushed a French force at Baylen and a British army landed in Portugal under Sir Arthur Wellesley, the future Wellington, who beat General Junot at Vimeiro on 21 August. Napoleon himself led some 250,000 men of his Grande Arme into Spain in the late autumn of 1808, swept everything before him and marched into Madrid on 4 December to reinstall his brother on the throne.

The British army in Portugal was now commanded by the talented Sir John Moore, one of the pioneers of light infantry tactics. In the first week of October, he had received instructions from the British government to take most of his army into Spain leaving 10,000 men in Portugal. Once in Spain, he would join forces with another British force that would land at Corunna. The British army was to support the Spanish armies in their attempt to encircle the invading French in northern Spain. Moore had left 9,000 men at Almeida and entered Spain on 16 October with his 17,000 men to meet Sir David Bairds 12,300 marching into Leon from Corunna. Moore also sent all the guns he could spare towards Madrid by the Elvas route escorted by 4,000 men under LtGen Sir John Hope. This force included all the British cavalry in Portugal. Meanwhile, marshals Soult, Ney, Victor, Lefebvre and Bessires swept the Spanish aside and, before long, some 80,000 French troops were marching to meet the British. Moore, recognising his force was no match, retreated towards Corunna. Although Moore was killed in the ensuing battle outside the Spanish port city, the French were beaten off and the British army was evacuated to the relative safety of Portugal by the Royal Navy. Except for pockets in Andalusia and Valencia, much of Spain was now occupied by French troops. The Spanish armies, badly organised, led, trained and armed, could not stand against the superior French imperial troops. But with indomitable courage the Spanish never gave up the struggle no matter how desperate.

Meanwhile, in central Europe, Austria had declared war on Napoleon that spring, forcing the French emperor to gather most of his available troops to march on Vienna. Demonstrating his usual genius, Napoleon overcame the Austrians, occupying Vienna on 12 May 1809 and defeating the Austrian army at Wagram on 6 July. Smaller revolts in Germany were also crushed and even elderly Pope Pius VII, who had crowned Napoleon emperor in 1804, was not spared, with his Roman states annexed to the French empire by a decree of 17 May 1809.

1809 THE FOILED INVASION OF PORTUGAL

Portugal was now effectively the only large area of continental Europe where French troops could not march at will. There, at present beyond Napoleons reach, a sizeable British force remained and the Portuguese were rebuilding their army.

Napoleon was further disturbed by the course of events in Spain. Although the Spanish field armies were being defeated repeatedly, the emergence of the powerful guerrilla bands across the country had considerably complicated the situation. Napoleon knew of the British support to the Spaniards and to the guerrillas in particular something he greatly overestimated. One thing was certain, should the British be allowed to remain in Portugal for long the consequences would be disastrous for Napoleons control of Spain. This boil needed to be lanced, and quickly. Napoleon ordered Marshal Soult to invade northern Portugal from Vigo in Spain while Marshal Victor marched into Portugal further south. Hopefully, the combined might of both French armies would prove too much for the British and force them to evacuate Portugal.

Next page