Campaign 130

Kawanakajima 155364

Samurai power struggle

Stephen Turnbull Illustrated by Wayne Reynolds

Series editor Lee Johnson Consultant editor David G Chandler

CONTENTS

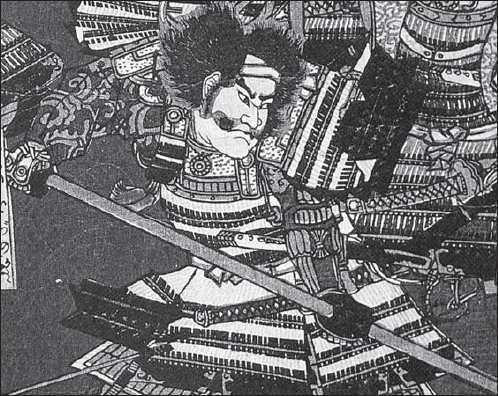

Takeda Shingen depicted in a particularly fierce mode in a scroll in the Watanabe Museum, Tottori. He is usually shown wearing this helmet with a horsehair plume. Note also his Buddhist monkskesa(scarf).

INTRODUCTION

The romance of Kawanakajima

T he story of the five battles of Kawanakajima, fought between the same armies in the same place over a period of 11 years, is one of the most cherished tales in Japanese military history, commemorated for centuries through epic literature, vivid woodblock prints and exciting movies.

The popular version of the story tells of a place deep in the heart of Japans highest mountains where two rivers join to form a fertile plain called Kawanakajima (the island within the river). Here the two great samurai clans of Takeda and Uesugi fought each other five times on a battlefield that marked the border between their territories. Not only were the armies the same, the same commanders led them at each battle. They were the rival daimyo (warlords) Takeda Shingen and Uesugi Kenshin.

In addition to this intriguing notion of five battles on one battlefield, Kawanakajima has also become the epitome of Japanese chivalry and romance: the archetypal clash of samurai arms. At its most extreme this view even denies that there were any casualties at the Kawanakajima battles, which are seen only as a series of friendly fixtures characterised by posturing and pomp. In this scenario the Kawanakajima conflicts may be dismissed as mock warfare or a game of chess played with real soldiers; an irrelevant but stirring tale of bloodless battles and gentle jousting.

I hope to destroy forever the myth that Kawanakajima involved nothing but mock battles. It is certainly true that in some of the encounters the two armies disengaged without the struggle becoming an all-out fight to the death. However, those casualties and wounds suffered were real enough.

With regard to the other aspects of the myth, there were indeed two great commanders. Each battle was fought between Takeda Shingen and Uesugi Kenshin, both individuals who loom large in Japanese history. There are strong veins of chivalry and romance, but these elements have to be seen in the context of some of the best-authenticated accounts of savagery in samurai history. In marked contrast to the tales of samurai glory, for example, the records of Kawanakajima contain strong evidence of cruelty to civilians; a topic otherwise hard to find in accounts of samurai warfare.

There is also the question of the authenticity of the remarkable notion of five battles fought on one battlefield. Unlike Japans three battles of Uji in 1180, 1184 and 1221, which were fought on one battlefield because they were all contests for control of the Uji bridge, the battles of Kawanakajima did not have a single focussed objective. They were fought at five different locations within the Kawanakajima area called Fuse, Saigawa, Uenohara, Hachimanbara and Shiozaki. To complicate matters further, an examination of the list of battlefields generates more than five battles! The battle of Fuse in 1553 is conventionally regarded as the first battle of Kawanakajima, but can only be understood in the context of the battles of Hachiman (of which there were two), fought just to the south of the Kawanakajima plain during the same year. The battle of Saigawa (the second battle of Kawanakajima) in 1555 was an indecisive standoff almost overshadowed by the nearby siege of Asahiyama. The third encounter, the battle of Uenohara in 1557, was fought further away from Kawanakajima than any other of the five and took place after the bitter siege of Katsurayama castle. The succession of events that included the fifth battle finished with another standoff when almost no fighting took place at all. It may even be possible to label another encounter in 1568 as the sixth battle of Kawanakajima. In fact only the fourth battle at Hachimanbara in 1561 was fought in the heart of Kawanakajima. This great battle overshadows the others as the culmination of the struggle, so that to many historians it is the Battle of Kawanakajima. It is the fourth battle of Kawanakajima at Hachimanbara that is the main focus of this book.

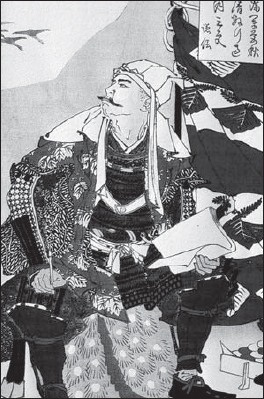

Uesugi Kenshin is seen here in a very contemplative mood, as shown in a print by Yoshitoshi. Uesugi Kenshins adoption of the life of a Buddhist monk was expressed in ways that stood in marked contrast to that of Shingen. Kenshin never married, and appears to have remained celibate all his life.

Thus one could argue that there was in fact only one battle of Kawanakajima: equally by using a different counting system the number of separate engagements could be as high as eight. This is not quite the end of the matter, because if we define the battles by their general location in the Kawanakajima area and do not limit them to Takeda/Uesugi encounters, then the battles fought there in 1181, 1335 and 1399 should possibly be included, giving 11 battles of Kawanakajima surely a world record!

I have taken the approach of viewing Kawanakajima 155364 as five separate but related campaigns fought over a period of 11 years against a common strategic background. The catalyst for the long struggle was Takeda Shingens desire to conquer Shinano province. Kawanakajima lay practically on the border between Shinano and the province of Echigo. Echigo was the territory of Uesugi Kenshin, who was determined to stop his neighbour in his tracks.

Kawanakajima 155364 represents a transitional period in samurai warfare, and for this reason alone the five campaigns repay careful study. They encapsulate a shift from a time when firearms were scarce to an age when they were plentiful, and from an age when campaigns were cut short by the demands of agriculture to a time when virtually professional armies of samurai did nothing but fight.

BACKGROUND TO THE CONFLICT

Japan in the Sengoku Period

The rivalry between the families of Takeda and Uesugi that found such memorable expression at Kawanakajima was in principle little different from many other conflicts that raged in various areas of Japan during the 16th century. This was Japans Sengoku Jidai the Age of Warring States an era of confusion and warfare that takes its name from the similar Warring States Period of Ancient China.

Japan was no stranger to war, and the combatants of the Sengoku Period often looked back to the time of their ancestors to find parallels and precursors to their own deeds of heroism. Many of these folk memories were focussed on the Gempei War, the great 12th-century civil war, from which one clan, the Minamoto, had emerged victorious to seize the reins of government. The divine emperor was relegated to the status of a figurehead, and from 1192 real power in Japan was in the hands of the Shogun, the military dictator from the samurai class.

The power of the Shogun waxed and waned as centuries passed. The Minamoto dynasty of Shoguns lasted only three generations, and a doomed attempt at imperial restoration during the 14th century merely replaced the Minamotos successors with another dynasty of Shoguns, the Ashikaga. The Ashikaga family proved much more successful at governing Japan, until a cataclysmic event in Japanese politics proved to be beyond even their control.