Campaign 54

Shiloh 1862

The death of innocence

James R Arnold Illustrated by Alan Perry

Series editor Lee Johnson Consultant editor David G Chandler

CONTENTS

Federal forces

Repercussions for the Confederacy

ORIGINS OF THE CAMPAIGN

T he United States strategic plan to subjugate the Confederate States of America regarded the Mississippi River as a corridor of invasion which could split the Confederacy. Key to the Mississippi was the border state of Kentucky. When war began, Kentucky maintained an uneasy neutrality as forces massed just over its northern and southern borders. Many believed that whichever side entered Kentucky first would throw the state into the hands of its rival.

The 1st Arkansas marched to battle at Shiloh cheering Sidney Johnston. Johnston responded, Shoot low boys; it takes two to carry one off the field. He told its colonel, I hope you may get through safely today, but we must win a victory. (National Archives)

Unperturbed by this, in the autumn of 1861 Confederate commander Major-General Leonidas Polk marched his men into Kentucky, believing that his move would pre-empt a Yankee offensive by Brigadier-General U.S. Grant. Polks impetuosity proved a mistake simply because the Yankees had more resources to bring to bear than did Polk. Grant countered Polk by rapidly occupying Paducah, in southwest Kentucky. Soon afterwards other Federal forces marched over the Ohio River into the Bluegrass State. Suddenly unshielded, the Confederacy lay vulnerable from the Mississippi River east to the mountains.

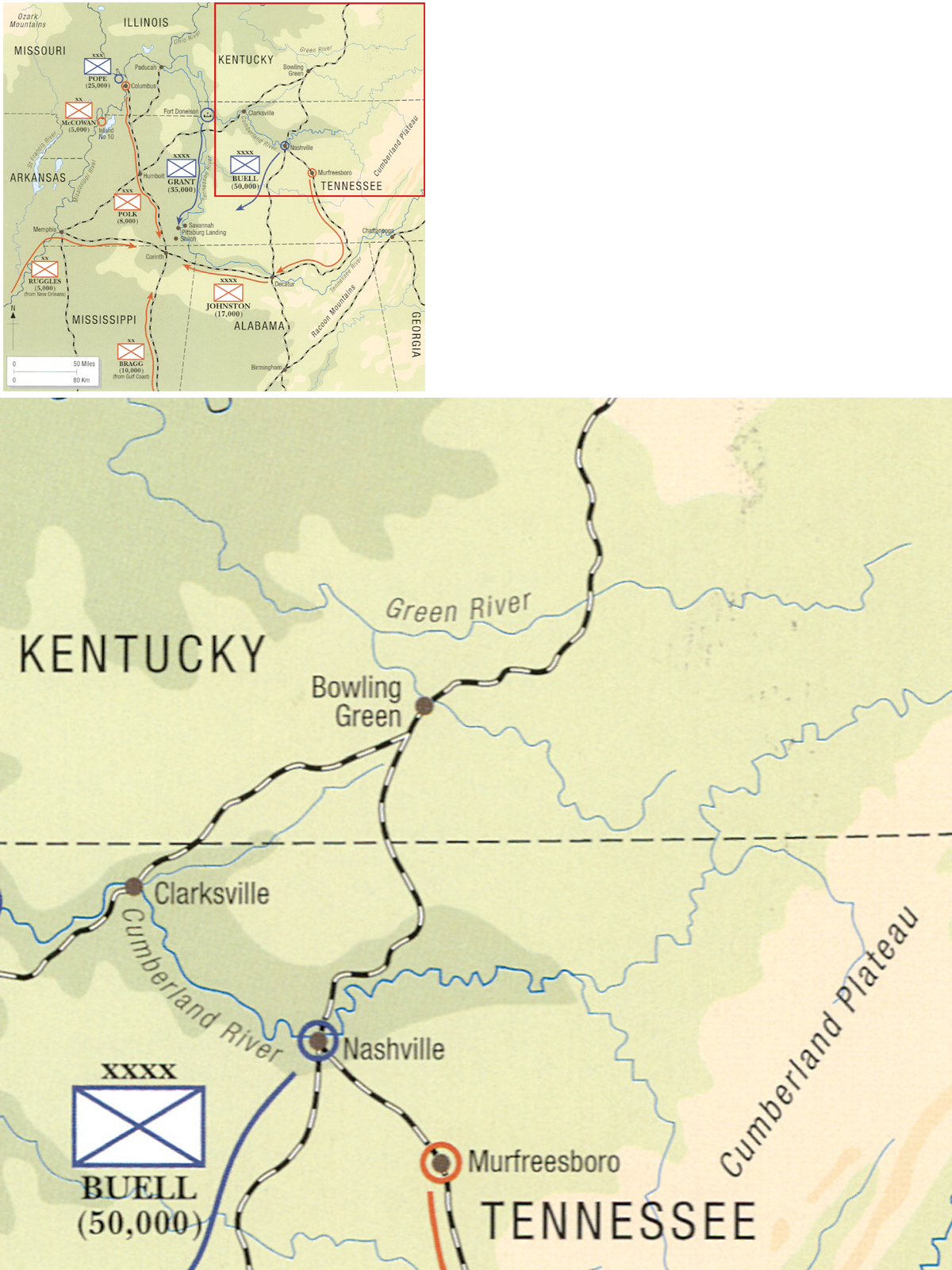

Confederate President Jefferson Davis dispatched the man he considered the nations ablest officer, General Albert Sidney Johnston, to the threatened sector. Johnston boldly advanced his small army to Bowling Green, Kentucky, and by so doing frightened his opponents into inactivity. Johnston stretched his forces to the breaking point as he tried to form a defensive arc covering the crucial Tennessee border. It was all a colossal bluff that gave false assurances to Confederate leaders, a bluff that Johnston knew would collapse when the Yankees found an aggressive fighting general.

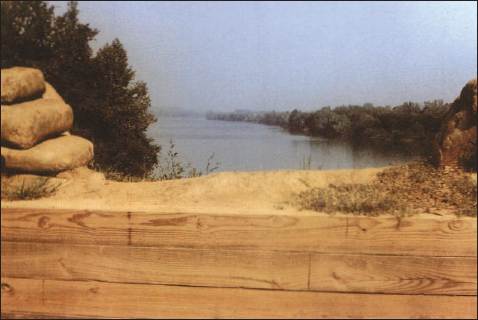

Confederate artillery sited on the Cumberland River stopped the Union gunboats at Fort Donelson. (Authors collection)

In the third week of January 1862, Johnston sent his superiors in Richmond an urgent dispatch: All the resources of the Confederacy are now needed for the defence of Tennessee. It was too late. Two weeks later, just as Johnston feared, the North found the determined officer who was willing to take risks. Grant advanced to capture Forts Henry and Donelson, the twin pillars that guarded western Tennessee, and thereby opened the way to the Confederate heartland.

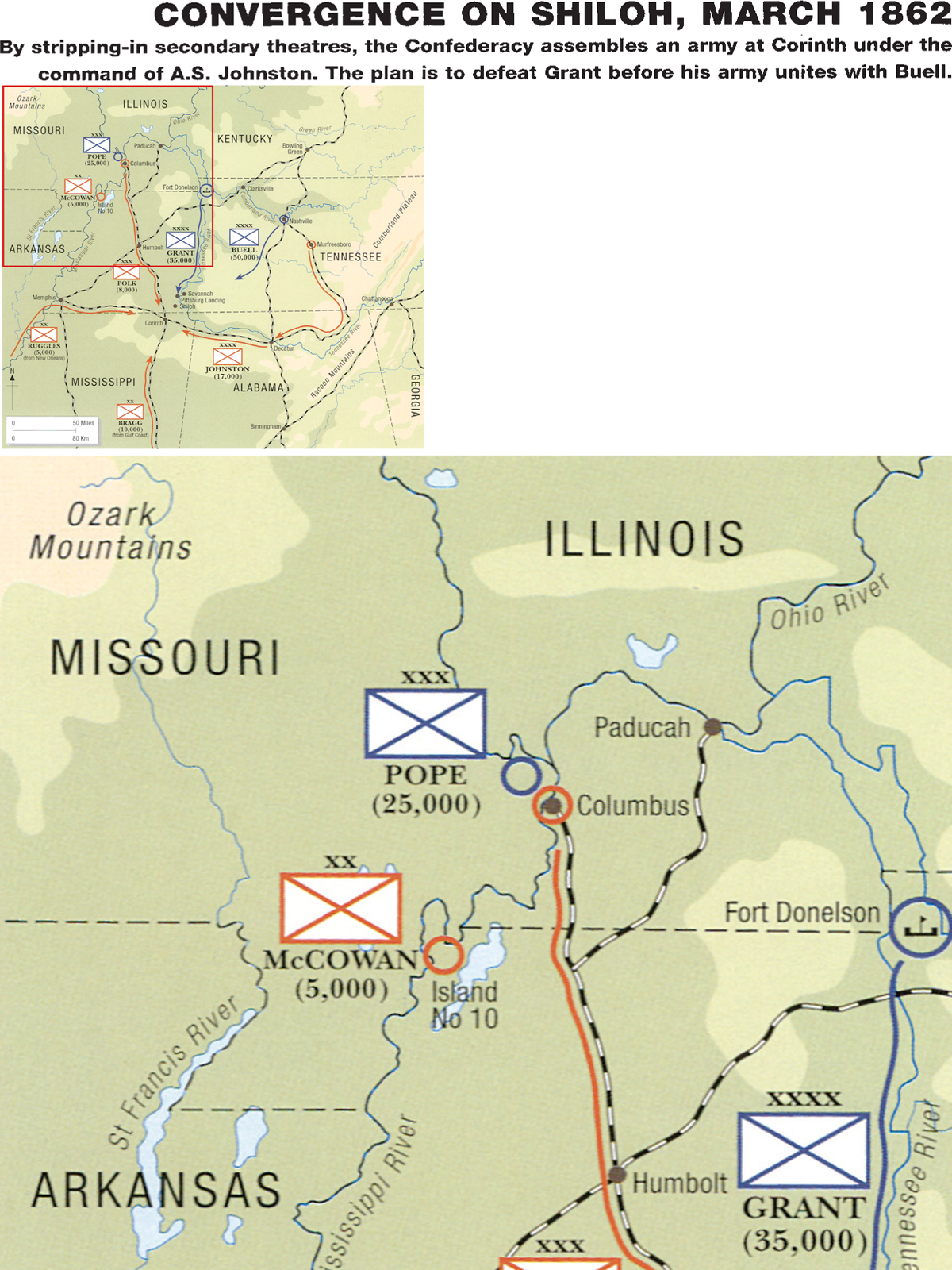

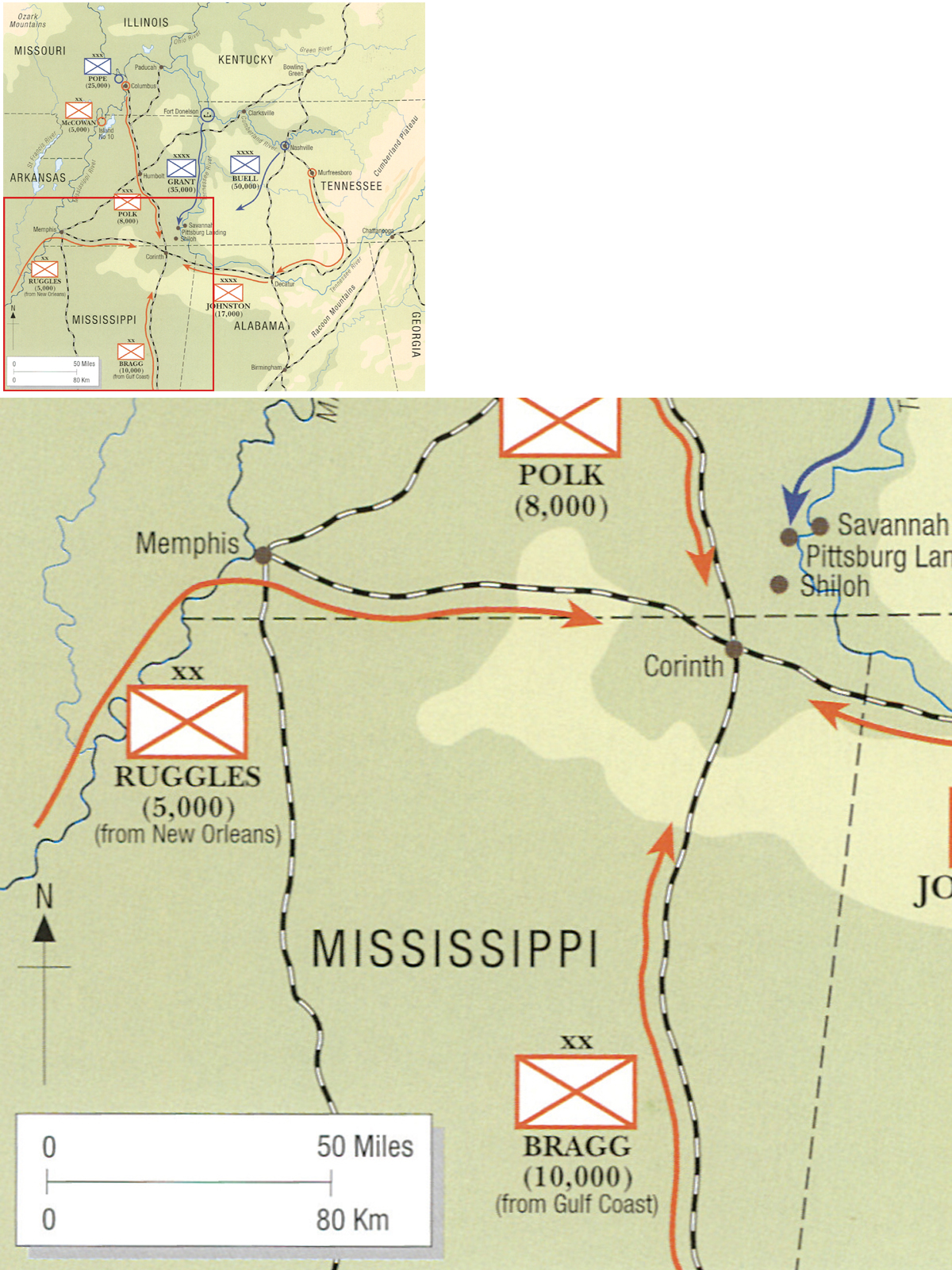

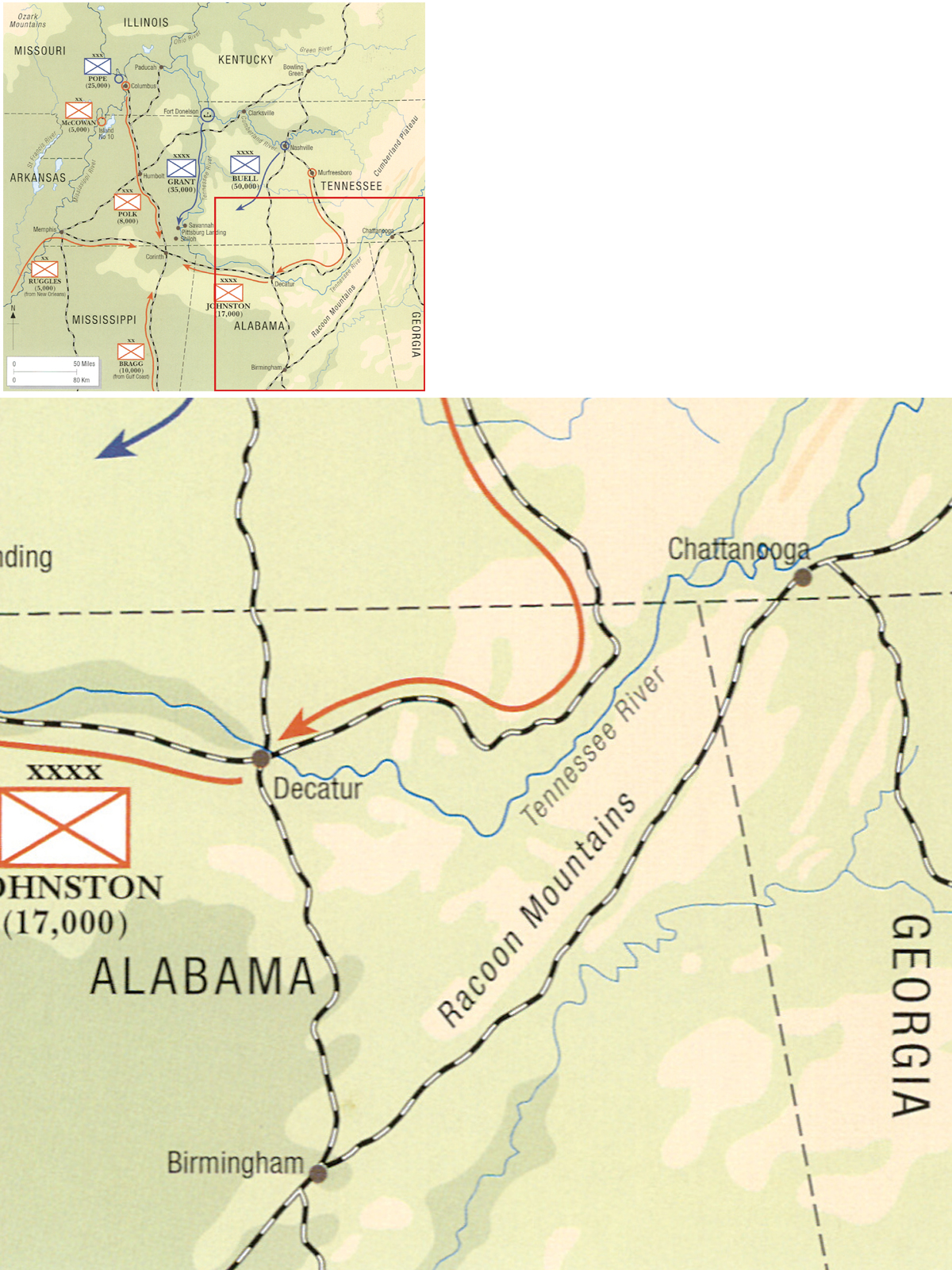

Across a 150-mile front stretching from the middle of Tennessee to the Mississippi River, three Federal armies lay poised to invade. To the west, Major-General John Popes 25,000-man force prepared to advance against a series of forts and batteries that blocked Federal naval movement down the Mississippi River. To the east, Major-General Don Carlos Buell massed a 50,000-man force at Nashville. In the centre, Grants men moved up the Tennessee River towards the important rail hub at Corinth, Mississippi. If these three armies co-operated, the outnumbered rebels would be hard pressed to oppose them.

Grant captured Fort Donelson by advancing against its landward side. The capture of Forts Henry and Donelson unhinged Sidney Johnstons defensive barrier and opened the way for the advance upriver to Pittsburg Landing. (Authors collection)

At this time of crisis Confederate Maj.Gen. Braxton Bragg was serving in a backwater command comprising Alabama and west Florida. From that vantage point he offered a persuasive strategic analysis. Bragg believed that the Confederate forces were too scattered. He recommended that secondary points be abandoned, that troops be ruthlessly stripped from garrison duty in order to concentrate at the point of decision, the portion of Tennessee occupied by Grants army. Bragg was certain that We have the right men, and the crisis upon us demands they should be in the right places. General P.G.T. Beauregard also believed in the virtues of concentration and agreed with Bragg. It would require a complex massing of men from five different independent commands. By rail, steamboat, and foot, soldiers would move from places as far distant as Mobile and New Orleans to join Sidney Johnston at Corinth. The planned counteroffensive was a high stakes gamble, but Jefferson Davis approved. The Confederate president understood that success hinged upon two factors: surprise; and striking before Grant received reinforcements from Buell.

Unbeknown to the rebel high command, several factors were working in favour of the counter-offensive. On 4 March 1862, Union Major-General Halleck relieved Grant of command because of alleged neglect and inefficiency. Grants senior divisional commander, General C.F. Smith, replaced him and began a march south from Fort Donelson in the direction of Corinth. As Smith advanced along the Tennessee River, he called upon a newly raised division under the command of William T. Sherman to raid downstream to cut the Memphis and Charleston Railroad. When this expedition became bogged down in torrential rains, Sherman sought a temporary base. He disembarked his men at the first place above water. Located on the western bank of the Tennessee River, its name was Pittsburg Landing. Inland, about four miles to the south, was Shiloh Church. The soaking Federal soldiers did not know that the ground from the landing to this church would become the scene of terrible battle.

Meanwhile, when President Abraham Lincoln heard that Halleck had relieved Grant, he was not happy. Lincoln was not about to lose his best (and at this point in the war apparently his only) fighting general. Down the chain of command came word that Halleck would have to provide detailed, specific information about the basis for his decision to relieve Grant. Although at times Halleck possessed a keen strategic mind, he was most comfortable when engaging in a hectoring, paper war against his subordinates. Like most bullies, when confronted with rival force he backed down. So it was when he received the War Departments request regarding Grant. Correctly judging the political winds, he wrote to Grant, Instead of relieving you, I wish you as soon as your new army is in the field to assume the immediate command and lead it on to new victories.