Campaign 10

First Bull Run 1861

The Souths first victory

Alan Hankinson

Series editor Lee Johnson Consultant editor David G Chandler

CONTENTS

INTRODUCTION

Bull Run is a pleasant, gently flowing river in northern Virginia, which runs through rolling green farmland on its way to join the Potomac. By American standards it is not much of a river, but it is wide and deep enough to present problems to an army on the move. The United States capital, Washington, is some 25 miles away to the northeast. The city of Richmond, Virginia, which became the capital of the break-away Confederate states in 1861, lies 80 miles or so to the south. The fact that it lay between these opposing capitals, abetted by the fact that it was close to the railway junction of Manassas, meant that a few acres of this peaceful countryside formed the stage for two fierce battles within the first fourteen months of the American Civil War.

The First Battle of Bull Run is significant for several reasons. It was the first major encounter of the war, and it is possible that had victory gone to the North, as it very nearly did, then the war which was to go on for nearly four more years and to claim the lives of more than 600,000 men might have ended then. It was the first battle ever fought in which the movement of men by railway played an influential part. And it taught both sides that they were in for a long struggle, which would not be won merely by dash and gallantry.

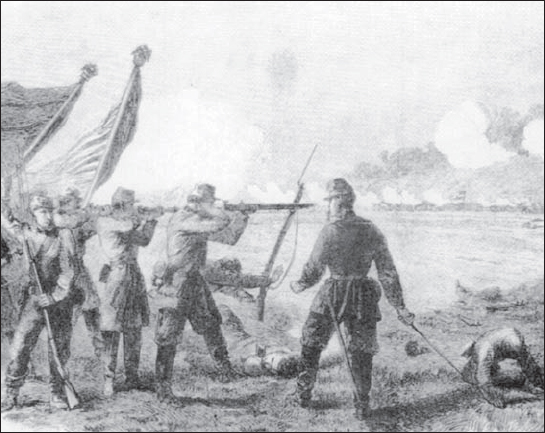

Scene of the battles turning-point: the slopes leading up to Henry House and the summit plateau. The slight depression in the ground, where the trees stand, afforded the attacking Northern regiments a little cover, but once they were over the crest they came under withering fire from Jacksons line.

From the military point of view, the lessons it taught were negative. Neither army was ready for battle; the men were untrained, the commanders inexperienced. There was no inspired generalship. The issue was decided more by luck than by anybodys good management. It was a demonstration, more than anything else, of all-round military incompetence.

THE WAY TO CIVIL WAR

Hollywood films have conditioned the world to see the United States of America in the first half of the nineteenth century as a land of violence bitter feuds and banditry, shoot-outs and lynch mobs, and incessant Indian wars. English visitors at the time, such as Frances Trollope, Harriet Martineau and Charles Dickens, portrayed it as a crude and mannerless society, full of tobacco-chewers and spitoons, loud with drunks and their public brawling. In fact, though, to most of those who lived there then, and especially the hundreds of thousands who had recently escaped from the persecutions and deprivations of Europe, it was a land of boundless opportunity and optimism. The United States was a young country, still united, comparatively peaceful and, by world standards at the time, highly democratic. It was also prosperous and expanding. The population was growing rapidly. Vast new territories were constantly being added to the Union, with broad rivers and fertile plains and hills that were rich in minerals. A complex network of railways sprang up to make transport easier and faster. In the North, towns were growing into cities and many new industries were appearing. Every ship that arrived from across the Atlantic brought hundreds more immigrants from the old world, most of them young, many of them with specialist skills, all of them ambitious to make their fortunes in this brave new world. The society they joined was tough and competitive. The rewards went to those who were strong and resourceful and ready to work hard. But the prizes were worth the winning and, compared with the countries they had left behind, there was remarkable freedom to pursue them.

But the very speed with which the country was growing and changing created strains. In a sense, three different countries were emerging. The West, where new territories were continuously opening up, was the place for pioneers; life there was primitive; families and communities had to be tough and self-reliant. The North-East was much more settled and it was here that towns were growing into cities and new industries were springing up. All was change and bustle in this region as descendants of the original colonists, mostly English, were joined by a heady ethnic mix of Italians and Irish, Scots and Germans, Slavs and Scandinavians and others. And the South was another world entirely, a near-tropical land of great plantations where white land-owners enjoyed a privileged and leisurely way of life. Unlike the other two regions, society here was static, rigidly based on conventions, fixed and hierarchical.

There were not only wide differences in character and climate; there were conflicts of interest too. The North, for example, wanted high tariff barriers against imports from abroad to protect nascent industries from European competition. But the South, heavily dependent on exports of cotton and tobacco to Europe, wanted free trade. Many Southerners feared, with good reason, that it was only a matter of time before the population disparity would be such that their interests would be over-ridden by the other parts of the Union. As early as the 1820s there had been talk, among the more extreme elements in the South, of secession, breaking away from the Union to go it alone.

The Slavery Issue

Even so, the majority of Americans cherished the notion of their countrys manifest destiny, the idea that the push westwards would be maintained until they had built a vast and powerful nation from sea to shining sea. The power of this vision, and the regard many held for the founding fathers and the unique democratic republic they had created, would almost certainly have held the country together had it not been for one further factor: the institution of chattel slavery.

By 1860 there were well over three million negro slaves in the southern states, most of them labouring on the plantations. The invention of the cotton gin, making the short-staple cotton that grew so abundantly there suitable for processing in the textile mills of Europe, paved the way for a lucrative export industry. In 1860 cotton represented 57 per cent of the value of all Americas exports. The business was based on the labour of the slaves, descendants of West African tribes-people who had been shipped across the Atlantic in colonial times. The slaves were property bought and sold at the markets, owned and entirely controlled by their white masters.

Slavery had died out in the northern states, for economic rather than for moral reasons. But, as the years passed, an increasing and increasingly vocal body of opinion grew up, demanding that slavery be abolished throughout the Union. By the middle of the nineteenth century, however, this was still a minority feeling. Most moderate opinion in the North, however much it disapproved of slavery in principle, was prepared to accept its existence in the South as a fact that had to be recognized. And most reasonable men in the South were happy enough to stay in the Union so long as there were no direct attempts to end the system by which they lived.