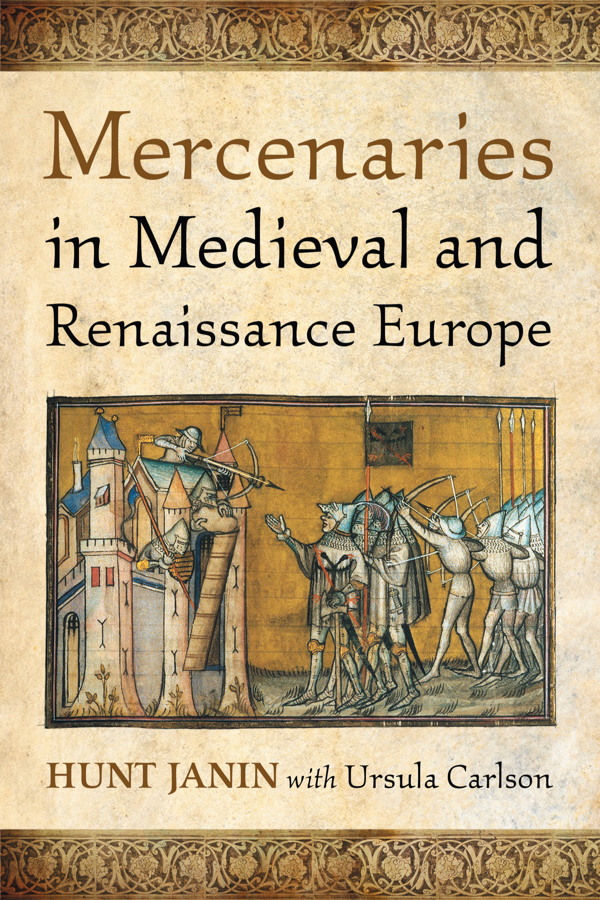

Mercenaries in Medieval and Renaissance Europe

Hunt Janin with Ursula Carlson

McFarland & Company, Inc., Publishers

Jefferson, North Carolina, and London

Hunt Janin has written or cowritten 10 other books for McFarland: Rising Sea Levels (and Scott A. Mandia, 2012), Trails of Historic New Mexico (and Ursula Carlson, 2010), The University in Medieval Life (2008), Islamic Law (and Andr Kahlmeyer, 2007), Fort Bridger, Wyoming (2006), The Pursuit of Learning in the Islamic World, 6102003 (2005; paperback 2006), Medieval Justice (2004; paperback 2009), Four Paths to Jerusalem (2002; paperback 2006), Claiming the American Wilderness (2001; paperback 2006), The India-China Opium Trade in the Nineteenth Century (1999)

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGUING DATA ARE AVAILABLE

BRITISH LIBRARY CATALOGUING DATA ARE AVAILABLE

e-ISBN: 978-1-4766-1207-2

2013 Hunt Janin with Ursula Carson. All rights reserved

No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying or recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher.

Cover art: The taking of Pestien (folio 51), Jean Cuvelier, La Chanson de Bertrand du Guesclin, Paris, 13801392 (British Library)

McFarland & Company, Inc., Publishers

Box 611, Jefferson, North Carolina 28640

www.mcfarlandpub.com

Now we must consider yet another category of man-at-arms who deserves much praise. That is the one who, for various compelling reasons ... leaves his locality ... before he has gained any reputation there, [even though] he would have preferred to remain in his own region if he could well do so. Nevertheless [such men] leave and go to Lombardy or Tuscany or Pulia or other lands where pay and other rewards can be earned.... Through this they can see, learn and gain knowledge of much that is good through participating in war, for they may be in such lands or territories where they can witness and themselves achieve great deeds of arms.

Geoffroi de Charny, a French knight and author of three works on chivalry, who was killed at the battle of Poitiers in 1356 while he was carrying the Oriamme, the battle standard of the King of France, quoted in Caferro, John Hawkwood, p. 332.

Preface

Let us begin by dening a medieval or a Renaissance mercenary. These were mensome good, some badwho came from all walks of life and who had two things in common: they were professional soldiers, and they fought not because they were members of a specic political community but because they wanted to make money or otherwise be rewarded. Since they used the same tactics, weapons, and equipment as non-mercenary troops, all our comments on these matters apply equally well to mercenaries and non-mercenaries alike.

This book is a wide-ranging survey which addresses two fundamental questions:

Who were the medieval and Renaissance mercenaries?

What did they do?

Neither question has an easy answer. The rst question involves the complicated issue of what has been called the mercenary identity in the Middle Ages. It is very difcult for us today to say with great condence who was a mercenary and who was not. It is not simply a question of gain, since most mercenaries were paid in one way or another, either directly or indirectly (e.g., by capturing men who could be held for ransom, or by receiving tacit permission to rob, rape, and pillage on their own). Some more complicated cases include Merovingian antrustions, Anglo-Danish housecarls, discharged English soldiers, and Scottish soldiers in the pay of France.

Answering the second question denitively would require a more detailed knowledge of the daily life of mercenaries than is available today. What seems clear is that some adventuresome men living in troubled areas, e.g., in Flanders and northern Spain, were inclined to become mercenaries because their lives were already precarious and the risks of soldiering were mitigated by hopes of gain, e.g., booty and ransom.

We know very little about the personal lives of rank-and-le mercenaries because almost all of them were illiterate and few literate people wanted to waste their time recording the experiences of mercenaries. Some of the literate mercenary commanders had a good deal to say about the conduct of battles, honor, chivalry, and other noble subjects. But they had almost nothing at all to say about the common soldier who was trying to endure both the boredom and hardships of military life, and the blood, sweat, and mud of the battleeld, simply in order to draw his pay.

In studying this subject one must keep in mind the habit of contemporary chroniclers of greatly exaggerating the size of battles and the number of men killed, wounded, or taken prisoner. Here is one exceptionally dramatic example: during a papal campaign in Corsica in 14451446, chroniclers put the papal forces at 16,000 men. However, papal nancial records, which are far more accurate than the chroniclers, show that the strength of the papal army there cannot have been much above 1,000 men.

This book presents a large number of vignettes focusing on mercenaries in Western Europe over a period of nearly 900 years. This approach seems to offer a couple of advantages:

It offers some answers to the questions above; and

It breaks up the long history of medieval and Renaissance mercenaries into manageable chunksletting the reader focus on particularly interesting moments of mercenary history.

Most chapters begin with a short paragraph in italics highlighting the three to ve vignettes to be discussed in that chapter, usually in chronological order. The chapter titlesoften short extracts from the contemporary sources quoted in the textare derived from these events or individuals.

The Introduction offers a broad overview of medieval and Renaissance warfare. Chapter I introduces some of the mercenaries and the tools of their trade. Chapters II through XI focus on a selection of the most memorable individuals and events of mercenary historyfrom the Merovingian mercenaries of 752, who were arguably the rst medieval mercenaries known to us, to the very late Renaissance mercenaries of the Thirty Years War, which ended in 1648 and which we shall set as the outermost limit of the Renaissance. The Conclusion offers summary remarks.

Mercenaries played violent and colorful roles in warfare but they have not received a great deal of scholarly attention compared to other aspects of medieval life. The present authors have therefore tried in a modest way to correct this situation. Toward that end, quotations from contemporary or near-contemporary observers have been used frequently. Chapter notes (at the end of the book) have been used extensively: for scholarly attribution, to explain medieval or Renaissance matters that may be unclear to the reader, and in some cases to make substantive points which are important but are too detailed to appear in the text itself. Readers who want more information on matters discussed in the text will nd some excellent sources listed in the bibliography. Two appendices discuss armor and Swiss mercenaries.

The authors are grateful for the good advice we have received from Dr. William Caferro and especially from Dr. John France,who very kindly read much of the manuscript in draft and has made a number of extremely useful corrections and suggestions. We are also grateful to Dio Koolen and to Martine Kommer for their help in translating quotations from medieval Spanish and from medieval French. Alexandra Janin has earned our thanks for her indexing work. Any errors or omissions in the text are of course our own doing alone.

Next page