MERCENARIES

AND THEIR

MASTERS

Warfare in Renaissance Italy

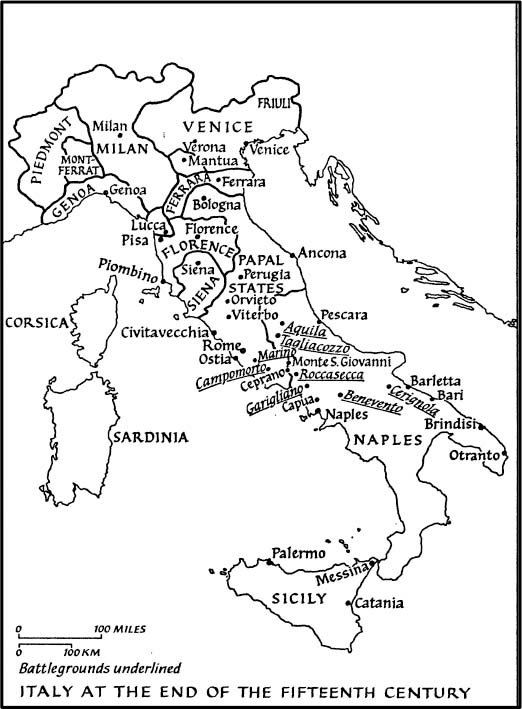

See also detailed map of Northern Italy (p.30) and Central Italy (p. 22)

MERCENARIES

AND THEIR

MASTERS

Warfare in Renaissance Italy

MICHAEL MALLETT

Foreword by

WILLIAM CAFERRO

Pen & Sword

MILITARY

First published in the Great Britain in 1974

Republished in this format in 2009 by

Pen & Sword Military

An imprint of

Pen & Sword Books Ltd

47 Church Street

Barnsley

South Yorkshire

S702AS

Copyright text Michael Mallett, 1974, 2009,

foreword William Caferro 2009

ISBN 978 184884 031 7

The right of Michael Mallett to be identified as Author of this work has been

asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

A CIP catalogue record for this book is

available from the British Library

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any

form or by any means, electronic or mechanical including photocopying, recording

or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission from the

Publisher in writing.

Printed and bound in England by

CPI Antony Rowe, Chippenham, Wiltshire

Pen & Sword Books Ltd incorporates the Imprints of Pen & Sword Aviation,

Pen & Sword Family History, Pen & Sword Maritime, Pen & Sword Military,

Wharncliffe Local History,

Pen & Sword Select, Pen & Sword Military Classics, Leo Cooper, Remember When,

Seaforth Publishing and Frontline Publishing

For a complete list of Pen & Sword titles please contact

PEN & SWORD BOOKS LIMITED

47 Church Street, Barnsley, South Yorkshire, S70 2AS, England

E-mail: enquiries@pen-and-sword.co.uk

Website: www.pen-and-sword.co.uk

CONTENTS

ILLUSTRATIONS

MAPS

The debts which an historian incurs are always difficult to enumerate and can never be fully acknowledged. However I have to thank the British Academy and the University of Warwick for research grants which enabled me to carry out some of the travelling around Italian archives which this book has involved. My debt to John Hale is apparent at many points in this book; his insights and enthusiasm for the subject have inspired me for many years. In addition I owe much to countless colleagues and students who have patiently listened to and commented on my ideas, particularly at the annual Warwick University Venice Symposium. For editorial help I am grateful to John Huntington, while for both material help and moral support it is to my wife, Patricia, that I owe my greatest debt.

M.E.M.

Since its publication thirty-five years ago, Michael Malletts Mercenaries and Their Masters has remained the point of departure for study of mercenaries and Italian warfare in the period from the thirteenth to the sixteenth century. Written with a casual elegance and in clear accessible language, it stands as the basic entre into the subject for both generalists and specialists alike. Over ten chapters, Mallett deals with an unparalleled range of topics, from recruitment, pay and contracts, to tactics and technical innovations, to camp life and social interaction, to administration, institutions and politics, to cultural and economic aspects. The topics, some merely suggestive, offer something to everybody. The book is rightfully considered the classic in its field.

For all its accessibility, however, Mercenaries and Their Masters represents an important revision of the subject. Professor Mallett consciously eschewed the earlier scholarly tradition of Charles Oman (Art of War in the Middle Ages, 1885) and others, who treated military history in terms of individual battles. Mallett departed also from prevailing trends that sought to understand medieval and Renaissance warfare in terms of modernity (Hans Delbruck, F. L. Taylor) and military revolutions (Michael Roberts and later Geoffrey Parker). For Mallet, warfare was inseparable from its political, economic, social and cultural context and thus could only be properly apprehended as a basic feature of Italian society. This was the case even though Italian states employed mercenaries, who, though inherently external and inadequate figures, were nevertheless part of the society served. In this regard, Malletts book should be judged alongside the work of such contemporaries as Philippe Contamine for France and Daniel Waley, D. M. Bueno de Mesquita and J. R. Hale for Italy, who treated war and soldiers in a similar fashion. Professor Hale was Malletts thesis advisor and close personal friend. The two collaborated on The Military Organisation of a Renaissance State: Venice c. 1400 to 1617 (1984), which amplified many of the issues raised in the current book, with specific regard to Venice. The work remains the standard study of the subject.

At the heart of Mercenaries and Their Masters are of course the mercenary soldiers themselves. Malletts temporal divisions are directly linked to the evolution of their service and to the evolution of Italian armies more generally. Mallet begins in the thirteenth century, when Italian states came progressively to rely on mercenaries, arrayed in bands of increasing size. He follows with analysis of events in the fourteenth century, the years 1320 to 1380 in particular, the era of the so-called companies and of foreign captains, during which Italian employers hired whole armies, which transformed themselves in times of peace into marauding bands. He then traces the rise of individual captains, the condottieri, from 1380 to 1420, who emerged apart from their bands; and the formation of more permanent armies and institutions in the period from 1420 to 1450, a time of intense inter-city warfare. Mallett focuses the majority of his attention on this last period, tracing myriad features in consecutive chapters entitled the organization, art and practice of war. Mallet ends with an important reinterpretation of the famous French invasion of Italy in 1494. He departs from previous views that stressed the technical inferiority of Italians, particularly with regard to artillery, and emphasizes instead political and strategic factors, including the failure of inter-state alliances and the weakness of Florentine defences in the Appenine passes, which allowed French forces to proceed largely unimpeded.

The figure of the Niccol Machiavelli (14691527) is always lurking in the background of Malletts analysis. The Florentine writer and political theorist condemned mercenaries as useless and dangerous and equated their service with a lack of native martial spirit that led directly to the humiliation of Italy by French and Spanish armies. Mallett deals with these arguments both implicitly and explicitly throughout the book, most conspicuously in the conclusion. In so doing, Mallett also positions his work against nineteenth-century Italian scholarship, inspired by Machiavelli and nationalistic feelings arising from the Risorgimento, that saw the Renaissance mercenary system as a distant mirror of native moral weaknesses that kept Italy divided in the modern age. Influential studies by Ercole Ricotti and Giuseppe Canestrini stressed in particular (like Machiavelli) the absence among states of native infantry. Piero Pieri in the twentieth century picked up on this theme, with alteration, and argued in Il Rinascimento e la crisi militare italiana (1952), a seminal book in the field, that the lack of infantry was a key difference between Italian armies and those of the rest of Europe, where Swiss infantry units and German

Next page