A Short

History

of the

Renaissance

in Europe

Margaret L. King

Copyright University of Toronto Press 2017

Higher Education Division

www.utppublishing.com

All rights reserved. The use of any part of this publication reproduced, transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, or stored in a retrieval system, without prior written consent of the publisheror in the case of photocopying, a licence from Access Copyright (the Canadian Copyright Licensing Agency), 32056 Wellesley Street West, Toronto, Ontario, M5S 2S3is an infringement of the copyright law.

Library and Archives Canada Cataloguing in Publication

King, Margaret L., 1947

A short history of the Renaissance in Europe/Margaret L. King.Third edition.

Revision of: King, Margaret L., 1947. Renaissance in Europe.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

Issued in print and electronic formats.

ISBN 978-1-4875-9309-4 (hardback).ISBN 978-1-4875-9308-7 (paperback). ISBN 978-1-4875-9310-0 (html).ISBN 978-1-4875-9311-7 (pdf).

1. Renaissance. 2. Humanism. 3. Civilization, WesternClassical influences. 4. EuropeHistory14921648. 5. EuropeCivilization. 6. EuropeIntellectual life. I. Title. II. Title: Renaissance in Europe.

CB361.K56 2016940.2'1C2016-901854-7

C2016-901855-5

We welcome comments and suggestions regarding any aspect of our publicationsplease feel free to contact us at .

North America

5201 Dufferin Street

North York, Ontario, Canada, M3H 5T8

2250 Military Road

Tonawanda, New York, USA, 14150

orders phone : 18005659523

orders fax : 18002219985

orders e-mail :

UK, Ireland, and continental Europe

NBN International

Estover Road, Plymouth, PL6 7PY, UK

orders phone : 44 (0) 1752 202301

orders fax : 44 (0) 1752 202333

orders e-mail :

Every effort has been made to contact copyright holders; in the event of an error or omission, please notify the publisher.

The University of Toronto Press acknowledges the financial support for its publishing activities of the Government of Canada through the Canada Book Fund.

Printed in Canada.

Table of Contents

Landmarks

Page List

Maps

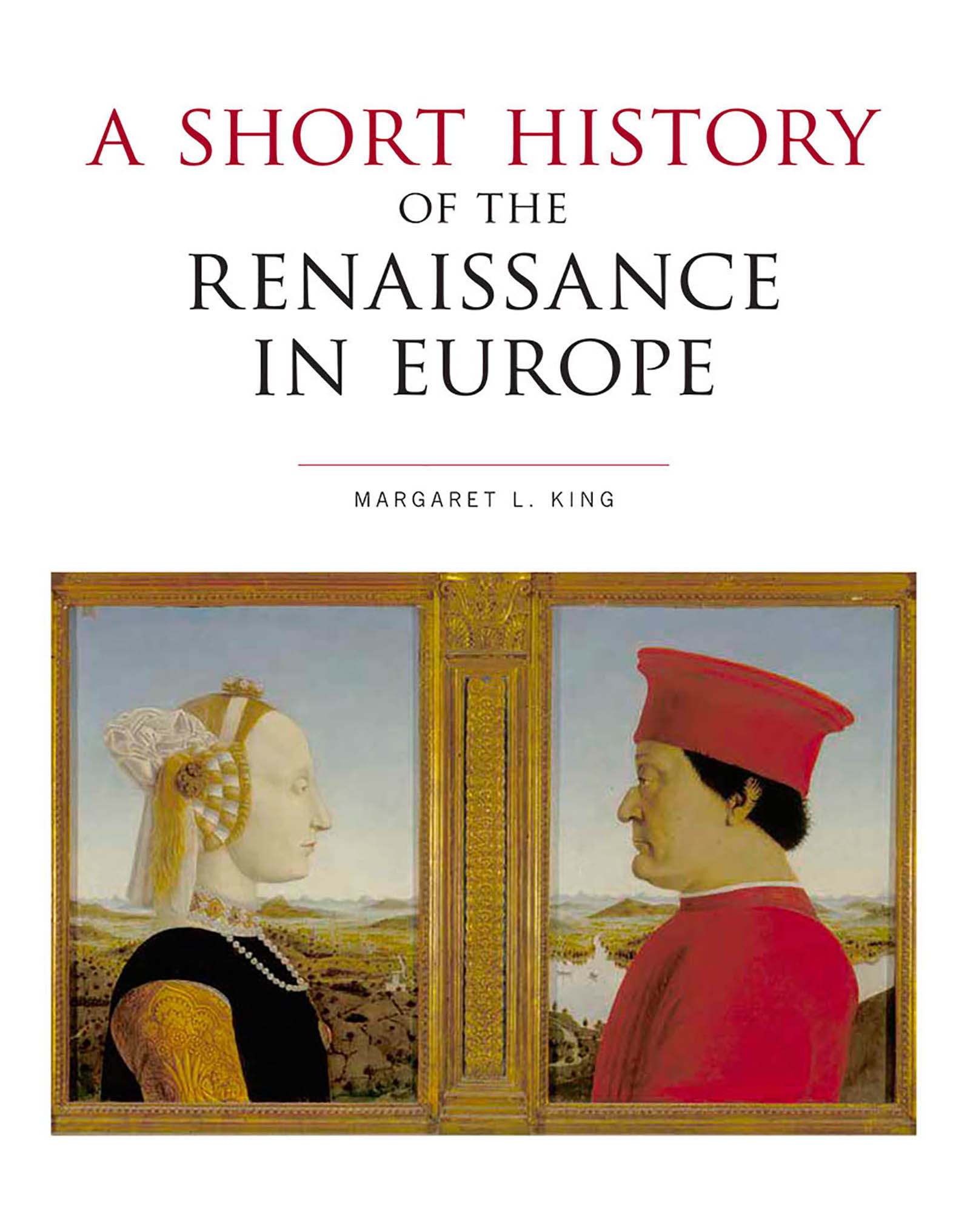

Illustrations

Figures, graphs, and Tables

Figures

Graphs

Tables

Acknowledgments

I have been living with the idea of the Renaissance for more than 50 years: longer than the 34 years I have been a mother, or the 40 I have been married, or the 40 I was employed by the City University of New York. In that long career, I have been informed and inspired by many scholars and studentsfar more than it is possible to name here, but I will name three who have been an unfailing source of inspiration and guidance: Paul F. Grendler, Paul Oskar Kristeller (19051999), and Albert Rabil, Jr. To them I am forever grateful. I am grateful as well to my new collaborators at the University of Toronto Press, whose idea it was to give this book on the Renaissance a renaissance of its own in a new and revised edition.

My father, deceased in 2012, always encouraged me in these scholarly labors he did not quite understandhe had been a builder of power plantsbut accepted nonetheless and lined the products up on his bookshelf. Heres another one, Dad. To my husband and sons and all my family, all my love forever. To my granddaughter Madeleine, I hope you will like the pictures in this book, which is for you.

Margaret L. King

Douglaston, New York

Introduction

The Idea of the Renaissance

Writing the history of the complex and protean idea of the Renaissance is a project as daunting as it is essential. It is not like writing the history of the Soviet Union, baseball, or the Platonic tradition, since there is scarcely anyone who doubts that these things existed or that they belong to a certain time and place. No such certainty prevails when it comes to the Renaissance. Not only do scholars not agree what the Renaissance is, they are not sure when or where or even if it took place.

Contemporary Views

The people who lived during the era we call the Renaissanceextending from approximately 1300 to 1700knew they were living in an extraordinary age. The fourteenth-century poet and scholar Francesco Petrarca (Petrarch; 13041374; see Chapter 2 ) looked back to the great achievements of the ancients, after which he saw only bleak decline until his own day in which, he believed, the world was becoming modern to the extent that it revived and relived antiquity. The sixteenth-century painter and historian of art Giorgio Vasari (15111574; see Chapter 4 ) detected the beginnings of a new vitality, an ability to understand and imitate nature itself, beginning in the last years of the thirteenth century and the early years of the fourteenth. The humanist scholars who recovered or discovered those ancient works that had been lost (rather, neglected) over the intervening years since the collapse of the Roman Empire often spoke of renovatio (renewal) and rinascita (rebirth).

The Modern Understanding of the Renaissance

Contemporaries did not, however, use the term Renaissance, a French word meaning rebirth and applied from the eighteenth century by art critics to the classicizing style of the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries. For the French historian Jules Michelet (17981874), who entitled the seventh volume of his 17-volume work on the history of France Le Renaissance (1855), Renaissance took on a larger meaning as a turning point in Western historyalthough Italy and the earlier stages of the Renaissance interested him little, and his Renaissance began instead with explorer Christopher Columbus (14511506) and reformer Martin Luther (14831546). The concept of the Renaissance won its modern currency in the work of the Swiss historian Jacob Burckhardt (18181897; see discussion under The Medium Renaissance below), whose Die Kultur der Renaissance in Italien (1860) circulated widely across the Atlantic in the English translation of S.G.C. Middlemore as The Civilization of the Renaissance in Italy.

Since Burckhardt defined the Renaissance as a key era in European history originating in Italy, many scholars have examined his arguments and agreed with, opposed, or reframed them in diverse ways. Their views of the Renaissance fall generally into three categories: small, medium, and large. The small-sized Renaissance constitutes a revival of classical forms and ideas. The medium-sized Renaissance involves a broader cultural resurgence. The large-sized Renaissance constitutes a historical era in itself, a period of two or three centuries that stands between the Middle Ages and the modern world.

The Small Renaissance

Adherents of the most restricted notion of the Renaissance focus on the revival of classical antiquity, especially in the arts and in thought and especially in Italy. They point to the artists who began to formulate new ideas about the relics of the ancient past littered about in the city of Rome, that had, for centuries, been understood primarily as the home of the papacy. Those artists sketched and imitated the arches, sarcophagi, and statues that had survived from a pre-Christian era and incorporated those forms into the Christianized culture of their own age. Scholars also note how Italian authors from the late thirteenth century followed classical models, as did the poet Dante, whose journey through the afterworld recorded in