ROUTLEDGE LIBRARY EDITIONS: THE RENAISSANCE

Volume 3

The Renaissance in Europe (14001600)

First published in 1933 by Methuen & Co. Ltd

This edition first published in 2020

by Routledge

2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon OX14 4RN

and by Routledge

52 Vanderbilt Avenue, New York, NY 10017

Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an informa business

1933 Trenchard Cox

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers.

Trademark notice: Product or corporate names may be trademarks or registered trademarks, and are used only for identification and explanation without intent to infringe.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

ISBN: 978-0-367-25398-1 (Set)

ISBN: 978-0-429-29609-3 (Set) (ebk)

ISBN: 978-0-367-27221-0 (Volume 3) (hbk)

ISBN: 978-0-429-29559-1 (Volume 3) (ebk)

Publishers Note

The publisher has gone to great lengths to ensure the quality of this reprint but points out that some imperfections in the original copies may be apparent.

Disclaimer

The publisher has made every effort to trace copyright holders and would welcome correspondence from those they have been unable to trace.

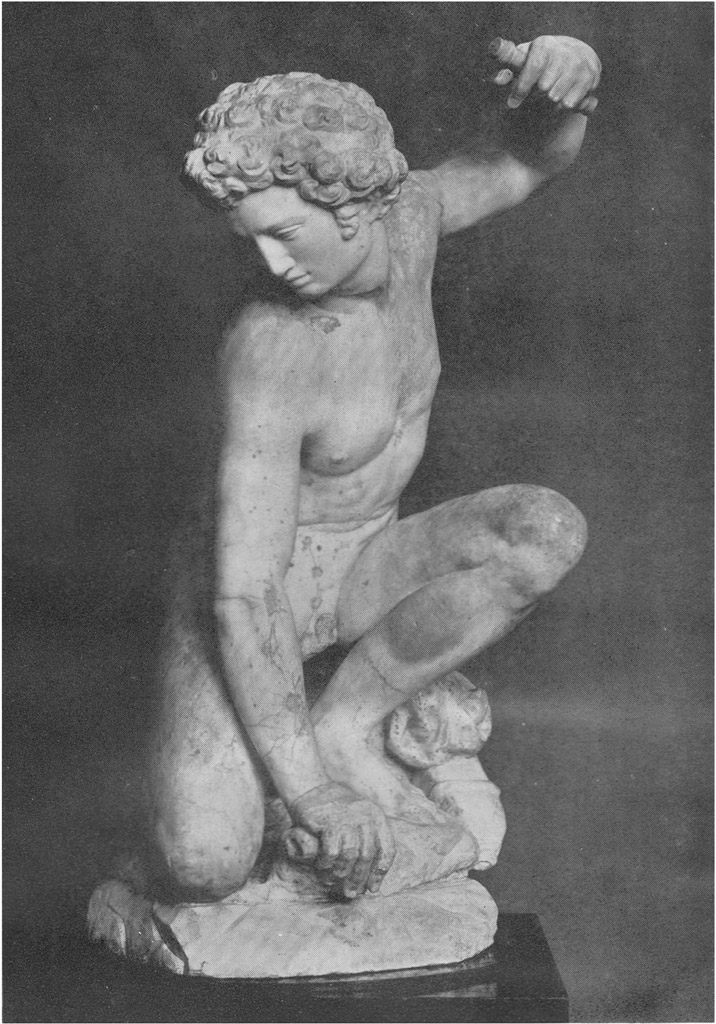

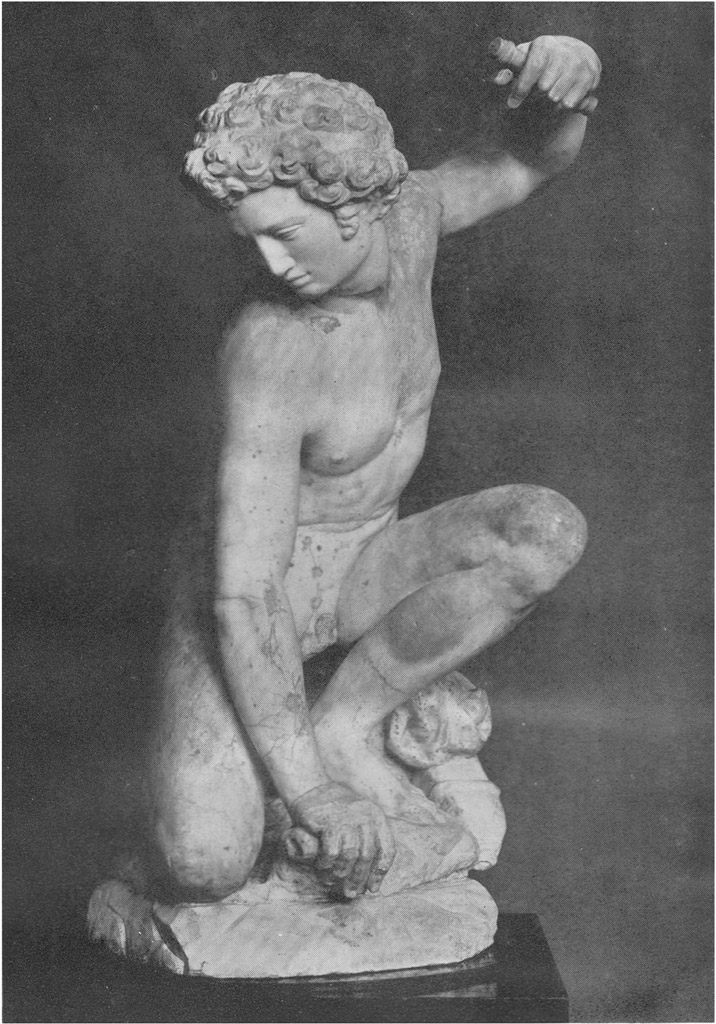

Michelangelo. Victoria & Albert Museum

The Renaissance in Europe (14001600)

BY

TRENCHARD COX

WALLACE COLLECTION

WITH 44 ILLUSTRATIONS

First Published in 1933

Printed in Great Britain

The design of this book needs explanation. Its aim is to trace a history of the European Renaissance with examples taken exclusively from works of art in London Museums and Art Galleries, where any member of the London public can see them for himself, without the cost of a ticket to the Continent.

A pretext, however, must immediately be made for the many omissions. To adjust such an extensive and infinitely various subject as the Renaissance to the confines of a single volume, discipline must be made the consort of enthusiasm, and limits in date must strictly be observed. My choice, therefore, of 14001600 as the cardinal points in my history, though it has given me the play of two entire centuries, has prevented me from discussing any artists of a later datefor example Caravaggio, Rubens, Rembrandt or Velazquez, who, even though they do not coincide with the true Renaissance era, were the Renaissance afterbirth. For a different reason, however, than lack of space England has been omitted from this book, since the Renaissance, as it affected our own country, will form the subject of a separate volume of this present series.

To the officials of the various Museums, who have permitted me to reproduce the treasures in their care my sincere thanks are due. But my personal gratitude is most warmly offered to Miss Beatrice Goldsmid, for the great encouragement which she gave to the work through each successive stage of its formation and to Mrs. Margaret Parkinson for her flawless typing of many a garbled manuscript. To the help of these two kind friends much of the pleasure, which has accompanied the making of this book, is due.

T. C.

B LAKENEY , N ORFOLK

Christmas, 1932

Contents

CHAP.

(Victoria and Albert Museum; Wallace Collection; Diploma Gallery, Royal Academy; Westminster Abbey; Record Office)

(National Gallery; National Portrait Gallery; Victoria and Albert Museum; Wallace Collection; Diploma Gallery, Royal Academy; Courtauld Institute of Art; Hampton Court)

(British Museum; Victoria and Albert Museum; Wallace Collection; Soanes Museum; Tower of London)

CHAP.

List of Plates

C UPID . By Michelangelo di Buonarroti

Victoria and Albert Museum

Victoria and Albert Museum

Victoria and Albert Museum

Victoria and Albert Museum

Victoria and Albert Museum

Victoria and Albert Museum

Victoria and Albert Museum

Diploma Gallery, Royal Academy

Chapel of Henry VII, Westminster Abbey

Victoria and Albert Museum

Victoria and Albert Museum

National Gallery

Wallace Collection

National Gallery

National Gallery

Wallace Collection

Diploma Gallery, Royal Academy

Victoria and Albert Museum

National Gallery

Courtauld Institute of Art

National Gallery

National Gallery

Victoria and Albert Museum

National Gallery

National Gallery

Hampton Court Palace

(Reproduced by gracious permission of H.M. the King)

National Gallery

National Gallery

National Gallery

National Portrait Gallery

Hampton Court Palace

(Reproduced by gracious permission of H.M. the King)

National Gallery

National Gallery

British Museum

Wallace Collection

Wallace Collection

Wallace Collection

Victoria and Albert Museum

British Museum (Barwell Bequest)

Victoria and Albert Museum

Illustration in the Text

T HE outbreak of the human spirit, which we call the Renaissance, found its symbol and epitome in Michelangelo, whose art was the complete expression of a time when human nature was enriched with a fresh and glorious dignity, and a new age was begun. The gigantic, exultant figures which people the Michelangelesque panorama are symbolic of the reawakening of the consciousness of Man to the wonders of the Universe; their Olympian beauty and unashamed nakedness epitomize a care for physical perfection; their arms, outstretched, embrace the advent of a new life which, in the fullness of its experience, would burst the bonds so long imposed by the stern religious system of the Middle Ages upon the heart and imagination.

A concise definition of the complex, many-sided movement known as the Renaissance would be superficial and misleading; it is, indeed, impossible to sum up a vast and unprecedented movement in a smart, succinct phrase of a few words. The Renaissance was hardly an historical event, but a rare phenomenon of nature in which the intellectual possibilities of Man were marvellously revealed. The movement, which began slowly, spread gradually over Western Europe and reached its height between the years 1400 and 1600, dates which can be considered the Pillars of Hercules in the history of its duration.

The external causes to which the Renaissance has been ascribed are well known and often quoted, and, even in the light of the new opinion which considers the Renaissance to have been the result of a gradual tendency rather than a sudden efflorescence, they remain unquestioned. Perhaps the Black Death, which ravaged Europe and the Far East in the fourteenth century, rang the final tocsin to Mankind, warning them to forgo their old-time ignorance and to pit a new knowledge against the dark powers of nature. The enfeeblement, too, of Feudalism had replaced authority by a cult of the individual, thereby reshuffling the social order. Finally, the fall of Constantinople, in 1453 into the hands of the Turks, marked the cataclysm of the Greek Empire and scattered Greek scholars, like a flight of doves, to bring the message of ancient Hellas to the notice of the Western world. From Constantinople, moreover, shiploads of looted manuscripts and sculptures found their way to Italy, adding stimulus to the immeasurable intellectual change effected by the discovery of printing, and the consequent dissemination of books and new ideas. Fresh sciences and new worlds were also discovered. The Copernican astronomical system took the place of the Ptolemaic, thus changing Mans conception of the Universe, whilst the discovery of America and the routes to the Far East opened up a glimpse of international possibilities in trade.