TITIAN AND THE END OF THE VENETIAN RENAISSANCE

TITIAN

AND THE END OF THE V ENETIAN R ENAISSANCE

TOM NICHOLS

REAKTION BOOKS

For Kerry

Published by

REAKTION BOOKS LTD

33 Great Sutton Street

London

EC1V 0DX, UK

www.reaktionbooks.co.uk

Copyright Tom Nichols 2013

All rights reserved

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publishers.

Page references in the Photo Acknowledgements and

Index match the printed edition of this book.

Printed and bound in China by C&C Offset Printing Co., Ltd

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

eISBN: 9781780232270

CONTENTS

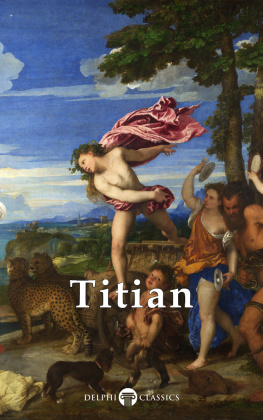

1 Titian, Piet, c. 157076. Gallerie dellAccademia, Venice.

Introduction

Titians Last Painting: The Sight of Death

The young Magdalene rushes away from the grim sight, back turned to the corpse, unable to look, her gesture a wave of horror rather than greeting (). The inertness of the object of his scrutiny is just another of the telling contrasts within the painting. The opposed colours of the flesh express the gulf between living and dead: Jeromes swarthy browns indicate the sensate flesh of life. Christs whitening pallor, on the other hand, appears through the loosening of the brushstroke on his upper body. The opacity of the colourless daubs of paint in this passage challenges mimetic function, dramatizing both the dissolution of Christs corporeal form and Jeromes struggle to understand the meaning of what he sees. The Virgin, mean while, retracts just slightly, offering a contrast to the saints urgent confusion. The outline of her cloak, recalling the age-old visual pattern of the Madonna of Mercy or Misericordia, suggests connection with her dead son. Yet with her strangely detached position, she too turns to look at his body, as if it were already a receding spectacle half-removed from her.

Titians dramatization of the conflicting emotions of those who witness Christs death lends his painting its bleakly expressive power. His focus effectively breaks up the usual formal unity expected of a piet, isolating its protagonists from one another to undermine more abstract possibilities of aesthetic harmony or resolved theological meaning. The subject of the piet, originally separated from the narrative flow of the Passion story is, in Titian, reintegrated into the world of events, its timeless iconic purity subjected to the rough and inarticulate chaos of human response. Given the dramatic intensity of Titians religious paintings, we might not have expected anything less: he had always made the immediate bodily experiences of his actors rebel against the prescriptions or closure of the narratives they enact. The story was never a given for Titian, but was taken as adventitious, unexpected, still unfolding. In the Piet something profoundly significant is happening but will never be completed, its inconclusiveness realized with unsettling force through the loose approximations of the brushwork.

There are visual precedents for the Magdalenes dashing posture and open-mouthed wail, not least among Titians own earlier paintings. The seamless pictorial realization of the painting is like a final proof of its comforting redemptive message, one secured precisely because nothing happens.

In Titians Piet a chapel with a half-dome apse and a mosaic ceiling is still present, a knowing half-reference to Bellinis model. Yet Titians architectural structure is, by comparison with Bellinis airy and light-filled chapel, a harshly impassive backdrop, its massive and weathered surfaces no longer integrated with the human figures before it. Even as we read its ancient symbolism (the outsize keystone as signal of Christ as foundation of the faith; the mosaic showing a pelican opening its breast to feed its young as recognition of his sacrifice; the prophetic sculptures of Moses and the Hellespontine Sibyl) the import of these stable iconographic signifiers is diminished. Their offer of thematic clarification is only apparent, the familiar symbolic structure made inert by the disintegrating drama of death played out in front of it. The enclosing architectural armature of chapel or niche, which had reflected the optimism and certainty of an earlier age, is no longer adequate to the task, dissolved under the impact of Titians blurring brushstrokes and made subject to the splintered experiences lived out in the fluid and amorphous space beyond its reach.

That this supplementary foreground space is conceived as contingent and personal is evident from Titians double self-representation here. At the lower right an archaic ex-voto picture is propped up, next to the painters family arms; a picture-within-a-picture featuring a self-portrait of Titian himself with his son Orazio kneeling before another, more heavenly, Piet group (

2 Detail of Titians Piet.

All this signals the gulf separating late Titian from his artistic forebears in Venice. But if so much can be read from the surface of his final painting, its place within the wider context of an attempted self-commemoration must also be explored. For its troubled history also brings to light the wider problem of Titians relationship with his adopted city of Venice and its cultural tradition.

An Inglorious Passing; or, The Difficult Case of the Piet

Titian intended his Piet to be placed on the altar above his own tomb in the grand Franciscan church of the Frari in Venice. Given its darkly ambiguous expressiveness, it comes as something of a surprise to find that Titians painting was meant as a heroic public monument to himself as an artist, a valedictory work that would provide a memorial focus at his grave. The intended function of the work explains, in part at least, the semi-concealed references to the painter, his son and family. The choice of the piet as a subject (very unusual in Venetian art of the sixteenth century) also makes more sense when the work is understood as being commemorative. The viewer would dwell on the deceased through the example of Christs own death. Perhaps there was also a more professionally competitive reason for the choice. Throughout his long career, Titian had compared himself to the great Michelangelo Buonarroti, and must have known about the Piet carved by the Florentine in the 1550s for his own tomb ( It is not difficult to read the radically pictorial quality of his Virgin and Christ as a last attempt to defeat his great rival as a final chapter in the professional paragone which would prove the superiority of oil painting over sculpture, Venetian art over Florentine, and Titian over Michelangelo. But the two works shared a common fate: neither was destined to be placed over the remains of their creators.