The German Genius

Europes Third Renaissance, the Second Scientific Revolution, and the Twentieth Century

Peter Watson

Contents

Blinded by the Light: Hitler, the Holocaust, and the Past That Will Not Pass Away

The Great Turn in German Life

Germanness Emerging

Bildung and the Inborn Drive toward Perfection

A Third Renaissance, between Doubt and Darwin

Winckelmann, Wolf, and Lessing: the Third Greek Revival and the Origins of Modern Scholarship

The Supreme Products of the Age of Paper

New Light on the Structure of the Mind

The High Renaissance in Music: The Symphony as Philosophy

Cosmos, Cuneiform, Clausewitz

The Mother Tongue, the Inner Voice, and the Romantic Song

The Brandenburg Gate, the Iron Cross, and the German Raphaels

The Rise of the Educated Middle Class: the Engines and Engineers of Modern Prosperity

Humboldts Gift: The Invention of Research and the Prussian (Protestant) Concept of Learning

The Evolution of Alienation

German Historicism: A Unique Event in the History of Ideas

The Heroic Age of Biology

Out from The Wretchedness of German Backwardness

German Fever in France, Britain, and the United States

Wagners Other RingFeuerbach, Schopenhauer, Nietzsche

Physics Becomes King: Helmholtz, Clausius, Boltzmann, Riemann

The Rise of the Laboratory: Siemens, Hofmann, Bayer, Zeiss

Masters of Metal: Krupp, Benz, Diesel, Rathenau

The Dynamics of Disease: Virchow, Koch, Mendel, Freud

The Miseries and Miracles of Modernity

The Abuses of History

The Pathologies of Nationalism

Money, the Masses, the Metropolis: The First Coherent School of Sociology

Dissonance and the Most-Discussed Man in Music

The Discovery of Radio, Relativity, and the Quantum

Sensibility and Sensuality in Vienna

Munich/Schwabing: Germanys Montmartre

Berlin Busybody

The Great War between Heroes and Traders

Prayers for a Fatherless Child: The Culture of the Defeated

Weimar: Unprecedented Mental Alertness

Weimar: The Golden Age of Twentieth-Century Physics, Philosophy, and History

Weimar: A Problem in Need of a Solution

Songs of the Reich: Hitler and the Spiritualization of the Struggle

Nazi Aesthetics: The Brown Shift

Scholarship in the Third Reich: No Such Thing as Objectivity

The Twilight of the Theologians

The Fruits, Failures, and Infamy of German Wartime Science

Exile, and the Road into the Open

Beyond Hitler: Continuity of the German Tradition under Adverse Conditions

The Fourth Reich: The Effect of German Thought on America

His Majestys Most Loyal Enemy Aliens

Divided Heaven: From Heidegger to Habermas to Ratzinger

Caf Deutschland: A Germany Not Seen Before

German Genius: The Dazzle, Deification, and Dangers of Inwardness

Thirty-five Underrated Germans

I n The Proud Tower , her splendid book about Europe in the run up (or run down) to World War I, Barbara Tuchman, the American historian, describes an incident in which Philip Ernst, the artist father of the surrealist Max Ernst, was painting a picture of his garden when he omitted a tree that spoiled the composition. Then, overcome with remorse at his offense against realism, he cut down the tree.

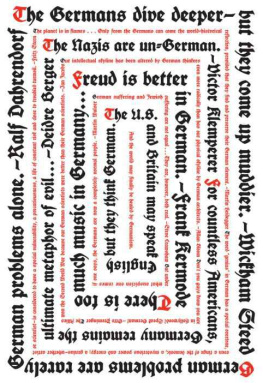

It is a good story. If one had to make a criticism it might be that it falls into the trap of stereotyping Germansas sticklers for exactitude, as pedantic and literal-minded. Part of the point of the book you are holding (as with the quotations given before the Table of Contents) is to go beyond stereotypes but also to show that the stereotypes peoples have of themselves can be as misleadingand as dangerousas the stereotypes their neighbors, rivals, and enemies have of them.

That is far from being the only point of the book, of course, which aims to be a history of German ideas over the past 250 years, from the death of Bach. No one can be an expert on such a long period, and in the course of my research I have been helped by a number of people whose assistance I would like to acknowledge here, some of whom have read all or parts of the typescript and offered suggestions for improvement. None of the names that follow, all of whom I thank warmly, is responsible for such errors, omissions, and solecisms that remain.

My first debt is to George (Lord) Weidenfeld, who encouraged me in this project and opened countless doors in Germany. I next thank Keith Bullivant, an old friend, now professor of Modern German Studies at the University of Florida but someone who, in 1970, with R. H. Thomas, founded the first ever Department of German Studies, at Warwick University. This is a direction now followed throughout the English-speaking world. But I also extend my gratitude to: Charles Aldington, Rosemary Ashton, Volker Berghahn, Tom Bower, Neville Conrad, Claudia Amthor-Croft, Ralf Dahrendorf, Bernd Ebert, Hans Magnus Enzensberger, Joachim Fest, Corinne Flick, Gert-Rudolf Flick, Andrew Gordon, Roland Goll, Karin Graf, Ronald Grierson, David Henn, Johannes Jacob, Joachim Kaiser, Marion Kazemi, Wolf-Hagen Krauth, Martin Kremer, Michael Krger, Manfred Lahnstein, Jerry Living, Robert Gerald Livingston, Gnther Lottes, Constance Lowenthal, Inge Mrkl, Christoph Mauch, Gisela Mettele, Richard Meyer, Peter Nitze, Andrew Nurnberg, Sabine Pfannensteil-Wright, Richard Pfennig, Werner Pfennig, Elisabeth Pyroth, Darius Rahimi, Ingeborg Reichle, Rudiger Safranski, Anne-Marie Schleich, Angela Schneider, Jochen Schneider, Kirsten Schroder, Hagen Schulze, Bernd Schuster, Bernd Seerbach, Kurt-Victor Selge, Fritz Stern, Lucia Stock, Robin Straus, Hans Strupp, Michael Strmer, Patricia Sutcliffe, Clare Unger, Fritz Unger, and David Wilkinson.

At the end of this book there are many pages of references. In addition to those, however, I would like to place on record my debt to a number of books on which I have relied especially heavilyall are classics of their kind. Alphabetically by author/editor they are: T. C. W. Blanning, The Culture of Power and the Power of Culture: Old Regime Europe, 16601789 (Oxford, 2002); John Cornwell, Hitlers Scientists: Science, War and the Devils Pact (Penguin, 2003); Steve Crawshaw, Easier Fatherland: Germany and the Twenty-First Century (Continuum, 2004); Eva Kolinsky and Wilfried van der Will, eds., The Cambridge Companion to Modern German Culture (Cambridge, 1998); Timothy Lenoir, The Strategy of Life: Teleology and Mechanics in Nineteenth-Century German Biology (Chicago, 1982); Bryan Magee, Wagner and Philosophy (Penguin, 2000); Suzanne L. Marchand, Down from Olympus: Archaeology and Philhellenism in Germany, 17501970 (Princeton, 1996); Peter Hanns Reill, The German Enlightenment and the Rise of Historicism (Berkeley, 1975); Robert J. Richards, The Romantic Conception of Life: Science and Philosophy in the Age of Goethe (Chicago, 2002). I also wish to thank the staff of the Goethe Institute, London, as well as the staffs at the cultural and press sections of the German Embassy in London, at the London Library, the Wiener Library, and at the German Historical Institutes in London and Washington, D.C.

A few paragraphs of this book overlap with material used in my earlier books. They are indicated at the appropriate places in the references. A handful of German words, difficult to translate, are used throughout the book. They are shown in italics at their first occurrence in each chapter, in roman thereafter.

Blinded by the Light: Hitler, the Holocaust, and the Past That Will Not Pass Away