Copyright 2014. All rights reserved, including the right to reproduce this book or portions thereof in any form, except for the inclusion of brief passages in an article, book or review.

ISBN 978-0-9883682-1-7

Table of Contents

Chapter 1

Ideology

Introduction

Certain historical eras are timeless in their facility to inspire curiosity and imagination. Ancient Egypt and Rome recall grandeur and power while the Renaissance stands as a marvelous expression of human creativity. Napoleonic France demonstrates that one man's purpose can define an age, and the American Wild West personifies the ruggedness and adventurous spirit of the pioneer generations that conquered a continent. There is much to be learned from milestones of civilization, though people interpret events differently, conforming to their particular beliefs and interests.

A comparative newcomer to the chronology of significant epochs is National Socialist Germany. Richly intriguing and not without arousing a sense of awe, she exerted tremendous influence in her time. The antithesis of democratic values in a century witnessing the triumph of democracy, Germany went down fighting. The task of recording the history of the period is therefore largely in the hands of the country's former enemies. One of the flaws in their annals is the superficial assumption that National Socialism was a rootless political program and the product of one man's world view. There was in fact a conscious endeavor by the National Socialists to align policies with German and European customs and practices. They believed their goals corresponded to the natural progression of their continent and found the diametrical Western-democratic concept to be foreign and immoral.

A political creed advocating freedom of choice, democracy ascended not through popular appeal, but through overwhelming economic and military force. This in no sense diminishes its claim to moral leadership in the realm of statecraft. Against somewhat novel democratic beliefs in multiculturalism, majority rule, feminism, universal equality and globalization once stood social and political conventions of Europe that had matured over centuries of conflict and compromise, of contemplation and discovery. The conviction that a nation possesses its own ethos, a collective personality based on related ethnic heritage and not just on language or environment, has no merit in democratic thinking; nor does the belief in a natural ranking within mankind determined by performance.

During the first half of the 20th Century, two world wars ultimately imposed democratic governments on European states that had been pursuing a separate way of life. One of the most successful weapons in the arsenal of democracy was atrocity propaganda. It demonized the enemy, motivating Allied armies and promoting their cause abroad. It justified the most ruthless means to destroy him. It defined the struggle as one of good versus evil, simplifying understanding for the populations of the United States and the British Commonwealth. The atrocities that Allied propagandists attribute to Germany, the backbone of resistance against Western democracy, remain lavishly publicized to this day. Conducted more zealously by the entertainment industry than by historians, this is largely an emotional presentation. The lurid appeal negates for the future a logical, impartial evaluation of political alternatives. This is unfortunate, since comparison is one of life's best tools for learning.

It is a common trait of human nature to often judge the validity of an argument less by what is said than by who is saying it. Casting doubt on the personal integrity of an opponent can be more influential than rational discussion to refute his doctrines. In Adolf Hitler, Germany had a wartime leader whose concept of an authoritarian, socialist state represented a serious challenge to democratic opinion. Indignant that anyone could harbor such views in so enlightened an age, and especially that he could promote them so effectively, contemporary historians provide a myriad of theories for his dissent. Thus we read that Hitlers obsession with black magic and astrology impelled him to start the war, he was mentally deranged due to inbreeding in the family, he was embarrassed by his Jewish ancestry, he was homosexual, he had a dysfunctional childhood, he became frustrated by failing as an artist, he was born with underdeveloped testicles and so forth.

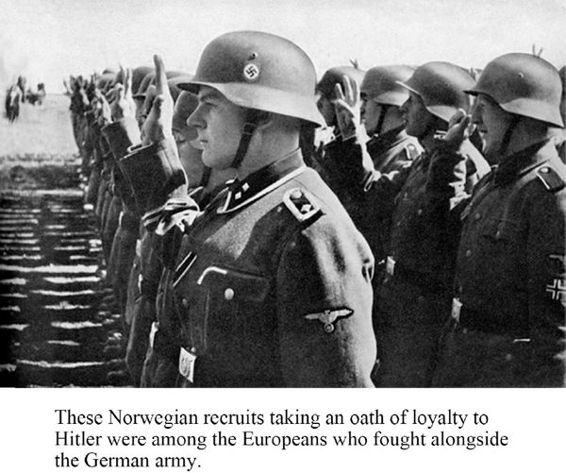

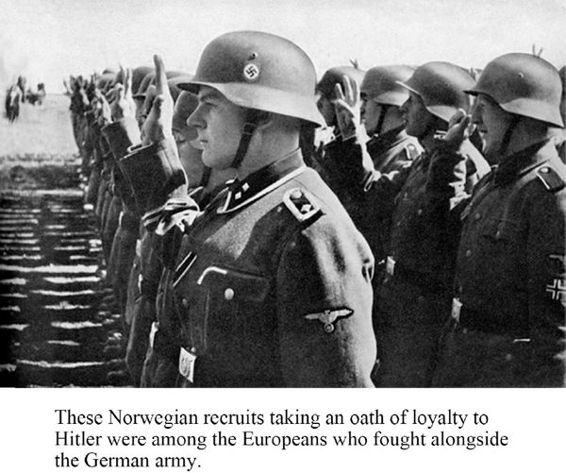

It would be more useful for the authors of such legends to question for example why, after the victorious Allies established democratic governments throughout Europe in 1919, this state form became practically extinct there in 20 years. Russia, Italy, Hungary, Poland, Lithuania, Austria, Germany, Greece, Spain, Slovakia, and soon thereafter France adopted authoritarian regimes. Several of these countries closed ranks with Germany. Hitler gave viable, popular political form to a growing anti-liberal tendency on the continent. Volunteers from over 30 nations enlisted to fight in the German armed forces during World War II. Only by the sword did the Western democracies and their Soviet ally bring them to heel. Surely the motives of such men merit investigation. Simply dismissing the leader who harnessed and directed these dynamic human resources as a demented megalomaniac is no explanation.

During the 1990s, Russian historians gained temporary access to previously classified Soviet war archives. In recent decades, the British government has gradually released long-sealed, relevant papers to the Public Record Office. Their perusal provides a more balanced insight into the causes of the war and the aims of world leaders involved. This study draws on the published research of primarily German historians, minimizing sources in print in English. This is to provide readers in America and in the United Kingdom with material otherwise unavailable to them.

Liberally quoting from German periodicals circulated during the Hitler era will acquaint the student of history with essential elements of National Socialist ideology just as it was presented to the German public. No one can accurately judge the actions of a people during a particular epoch without grasping the spirit of the times in which they lived. The goal of this book is to contribute to this understanding.

The Rise of Liberalism

National Socialism was not a spontaneous phenomenon that derailed Germanys evolution and led the country astray. It was a movement anchored deeply in the traditions and heritage of the German people and their fundamental requirements for life. Adolf Hitler gave tangible political expression to ideas nurtured by many of his countrymen that they considered complimentary to their national character. Though his opposition partys popular support was mainly a reaction to universal economic distress, Hitlers coming to power was nonetheless a logical consequence of German development.

True to the nationalist trend of his age, Hitler promoted Germanys self-sufficiency and independence. His party advocated the sovereignty of nations. This helped place the German realm, or Reich, on a collision course with a diametrical philosophy of life, a world ideology established in Europe and North America for well over a century: liberalism. During Hitlers time, it already exercised considerable influence on Western civilization. It was an ambitious ideal, inspiring followers with an international sense of mission to spread liberty, equality, and brotherhood to mankind. National Socialism rejected liberal democracy as repugnant to German morality and to natural order.

Next page