Researching and writing this book was a challenging and deeply meaningful undertaking, and there are many people to thank. First and foremost, I want to acknowledge and thank the editor Steven L. Mitchell, associate editor Sheila Stewart, and all the good staff at Prometheus for their insight and support of this book. Next, I want to thank my agent, Jeff Ourvan, for providing his invaluable encouragement and professional guidance throughout the process. Researchers Monika Malessa in Munich, Simon Fowler in London, and Amy Cheung von Haam in Los Angeles each made important contributions. Monika's research, translations, and familiarity with important archives were particularly exceptional. Andrew McCormick was very helpful with his mapmaking. Jonathan Hall took an early interest in the project and provided timely translations to help capture nuances in German I might have otherwise missed.

The professor and author Peter Longerich, who is among the most accomplished scholars in Germany on the Third Reich and the Holocaust, took time out of his busy schedule to offer me critical guidance. Dr. Klaus Lankheit of the Institut fr Zeitgeschichte (Institute for Contemporary History) in Munich went out of his way to facilitate my research and was truly inspiring and supportive. Kurt Eisner's foremost biographer, Bernhard Grau, kindly answered my questions about the former minister-president at his office in Munich. The author Andreas Eichmller, of the Documentation Center for the History of National Socialism in Munich, was also helpful when we met in the Bavarian capital. At UCLA, I had the privilege of studying under the psychohistorian Dr. Peter Loewenberg, who has made important contributions to our understanding of the history of early-twentieth-century Germany and the Third Reich. In addition, the writings of the philosopher and educator, Dr. Daisaku Ikeda were indispensable in helping me to gain insight into human nature, and formulate an approach to this subject.

Among the institutions, parks, and museums that helped provide historical perspective on Hitler and Nazism were the Institut fr Zeitgeschichte, the Documentation Center for the History of National Socialism in Munich and Obersalzberg, Dachau concentration camp, Auschwitz-Birkenau concentration camp, the Bavarian State Library, and the Simon Wiesenthal Center in Los Angeles.

When I began researching this subject, it was the curiosity of my dear friend and fellow filmmaker Darin Nellis that compelled me to pursue the question of how Hitler was made. Alex Ryan was another supportive filmmaker and friend whose creative instincts helped sharpen the narrative. The book wouldn't be what it is without the friendship and influence of Shinji and Donna Ishibashi, Jack and Janet Pickering, and Tom and Valeria Chu, who have also provided invaluable support to me over the years. So have friends like Peter von Haam. My father, Bill, and my brother, Jess, helped spark my initial interest in the subject of the book. In 1978, the past came alive when Dad took us on a tour through Germany and Austria to destinations including Berlin, Bayreuth, Nuremberg, and Vienna. I can still picture him leading us through the center of Munich to the Odeonsplatz, where he read passages from John Toland's Adolf Hitler to describe the Beer Hall Putsch. The trip included a visit to Dachau concentration camp, which made a lasting impression on me.

Among the most important contributors to this book is Dr. James Berenson, who helped bring me back from certain death when I was struggling with myeloma (bone marrow cancer) in 2014. At the time, I couldn't walk or sit up because of the degenerative effects of the illness. Dr. Berenson's treatment arrested my disease and stabilized it. It was during the time before I returned to health and started walking again that I began researching this book. At Dr. Berenson's clinic, fellow patients and nurses offered me great encouragement as I continued to write.

Finally, this work would not have been possible without the loving support of my wife and son, to whom the book is dedicated.

In October 1918, Adolf Hitler, while serving as a private in the German army, was temporarily blinded by a mustard gas attack. We were subjected for several hours to a heavy bombardment with gas bombs, Hitler later wrote in Mein Kampf, and about seven o'clock my eyes were scorching as I staggered back and delivered the last dispatch I was destined to carry in this war. A few hours later my eyes were like glowing coals and all was darkness around me.

Hitler claimed he decided right then and there to enter politics. But this was an embellishment: Mein Kampf was written six years later, and the story was enhanced to create emotional resonance between the author and the German people. Who were the despicable criminals that Hitler spoke of? What happened in the six years between Germany's surrender and the writing of Mein Kampf to radicalize this lowly private and allow him to become the most popular up-and-coming figure on the nationalist scene? Why were so many Germans susceptible to his point of view? To answer these questions, one must take stock of the terrible impact of the First World War. And consider the trenches of a battlefield Hitler never stepped foot in.

THE BROTHER OF THEM ALL

In the winter of 1916, the western front of the First World War extended four hundred miles from the North Sea in Belgium to the Swiss border of France. Facing one another in a series of trenches extending along the line, French, British, and German forces had reached a deadlock. To break the stalemate, the Chief of the German High Command, Erich von Falkenhayn, a handsome and distinguished Prussian senior officer, set his sights on Verdun, where he hoped to deliver a decisive blow. Situated in the French countryside, two hundred and fifty kilometers east of Paris, Verdun had come to symbolize the spirit of French resistance since the Franco-Prussian War of 1870. Falkenhayn had no intention of seizing the medieval city and its fortifications. Instead, he planned to lure the enemy into combat and kill them in massive numbers until they lost the will to fight. To make them bleed to death were the general's infamous words.

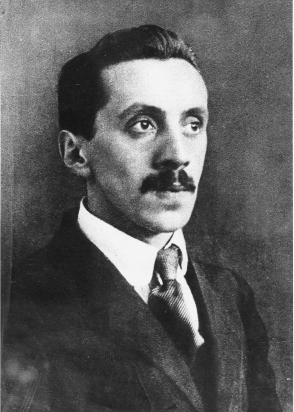

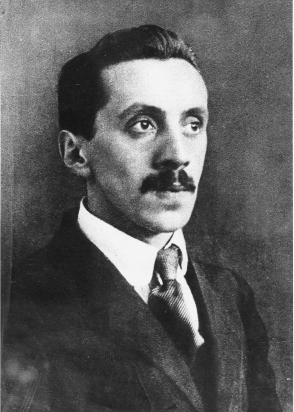

Among the Germans fighting on the front lines at Verdun was a pale young poet with deep-set eyes named Ernst Toller. At the time, no one could have known that the shy twenty-year-old would go on to play a key role in Bavaria's postwar revolution, become a world-renowned expressionist playwright, and a vociferous opponent of Adolf Hitler. Toller, who had been studying law at the University of Grenoble when the war was announced, departed France for Germany on one of the last trains before the French sealed the border in August of 1914.

Ernst Toller.

Toller had grown up in Samotschin, a town three hundred and forty-six kilometers east of Berlin, in present-day Poland, where he had the unpleasant childhood experience of being maligned as a dirty Jew.

Apart from the institutional prejudices, which curtailed his rise in rank, Toller found acceptance in the German army and seldom encountered anti-Semitism while in uniform.

But Toller, relegated to a muddy, rat-infested frontline trench, where the men of his unit were dying so quickly there was no place to dispose of the bodies, became soul-shocked. We did not bury our dead, Toller wrote. We pushed them into the little niches in the wall of the trench cut as resting places for ourselves. When I went slipping and slithering down the trench, with my head bent low, I did not know whether the men I passed were dead or alive; in that place the dead and the living had the same yellow-grey faces. Some soldiers had been blown to bits; others were caught in the barbed wire between trenches, their bodies rotting in the elements. Pieces of torn flesh littered the ground, and when the rats weren't stealing the soldiers food they were eating the dead. Then came Verdun.

Next page