As always, my wife Christine and our daughters, Hannah and Esther, supported me with their encouragement and interest as I researched and wrote, and we discussed many of the issues central to this book. I am very grateful.

I am grateful for assistance and advice from the following people whilst I was carrying out research into this book: Professor Richard Overy, Professor in History, Exeter University; Professor Richard J. Evans, Regius Professor of History, Cambridge University; Dr Kay Schiller, Senior Lecturer in the Department of History, Durham University; Wiltshire County Library Service and my friends at Bradford on Avon library. I am particularly grateful to my agent, Robert Dudley, and to Leo Hollis, my editor at Constable & Robinson, for all of their encouragement and support.

It goes without saying that all errors are my own.

The Third Reich remains one of the most striking episodes of world history in the twentieth century. The genocide against the Jews, the launching of the Second World War, the multiple abuses of power, the cruelty and suffering that were imposed on millions were all central features of Hitlers Nazi regime. Yet the Nazis were also highly successful in manipulating images and information: they mobilized and engaged vast numbers of people; they caught the imagination of the young and appeared remarkably modern to contemporary observers. This reminds us how complex the Third Reich was and how difficult to easily categorize. Was it aiming to create a throwback to a mythical past or was it looking forward to a brutally modernist and technologically advanced state? Was Hitler a strong and controlling dictator who achieved his clear goals, while dividing and ruling, or were his indolent personality and chaotic style of government the symptoms of a weak dictator who was unable to control the complex and contradictory forces that he unleashed? Was the Third Reich directed from above, or strongly influenced from below? Was it ruled by terror, or largely supported by a compliant German population ? Was Hitler a popular dictator? Was the genocide against the Jews a peculiarly German phenomenon, or a particularly German version of terrible wider trends?

The aim of this book is to explore these and other key questions and to give an overview of the complex evidence. Historians interpretations will be examined in order to suggest conclusions that take account of the different views that they represent. The evidence from the time itself is varied and complex: official statistics, state-sponsored art, secret police reports, public speeches and propaganda combine with diaries, letters and memoirs, humour and personal reminiscences to provide a multi-faceted view of life in the Third Reich. We will hear the thoughts of SS officers, German peasants, extermination-camp victims and survivors, opposition politicians, Nazi loyalists and resistance plotters, businessmen, ordinary men, women and children. Some will reveal the thoughts of insiders ; others will reveal the outlook and experiences of those who were very much outsiders in the ruthlessly categorized Third Reich.

Finally, it may be helpful to explain something of the approach of this book. History must put us firmly in touch with the lives of and issues facing people in the past. It is right that the examination of the evidence makes the personal experiences of those in the past more accessible, as well as outlining the wider processes and developments that acted on individuals. In order to assist in this balance, each chapter will frequently refer to individuals lives, thoughts and experiences in order to illustrate the wider issues in personal terms. In this way, we see the people within the history and appreciate how the historic events impacted on them. For in the vast numbers, appalling sufferings and huge distances covered in any history of the Third Reich, we must never lose sight of the individuals whose lives were caught up in these titanic events. For history is fundamentally about his-story and her-story

Anton Drexler was born in Germany in 1884 and first worked as a machine-fitter, before becoming a locksmith in Berlin in 1902. Despite his extreme nationalism he was judged physically unsuitable for military service and so, to his great disappointment, did not fight in the First World War. In 1919 bitter at the defeat of Germany and alarmed at the social and political turmoil of post-war Bavaria he co-founded the German Workers Party (the DAP) in Munich. Drexler was typical of a vulnerable section of the German population, the lower middle class. Possessing sufficient skills and independence to raise them above the mass of workers, such people were desperate to avoid any downwardly mobile pressures that might force them into the ranks of the working class. Made insecure by the economic and political upheaval in post-war Germany, such people were quick to blame Jews, socialists and communists for Germanys plight.

The DAP was only one of many tiny vlkisch (ethnic/racist) parties in Bavaria. Their common feature was their racist belief in the purity of German blood and German culture. Beyond that, their beliefs were a strange mixture of extreme nationalism, anti-Semitism and right-wing militarism, blended with a radical and semi-socialist resentment of capitalism, large department stores and unearned profits. As such, they were difficult to place on any political spectrum as they represented the anxieties, fears and resentments of those who felt themselves squeezed from above and below. Below them were the unionized workers with their internationalist allegiances to class rather than race; above them were the more comfortably off and the rich, whose nationalism was basically conservative.

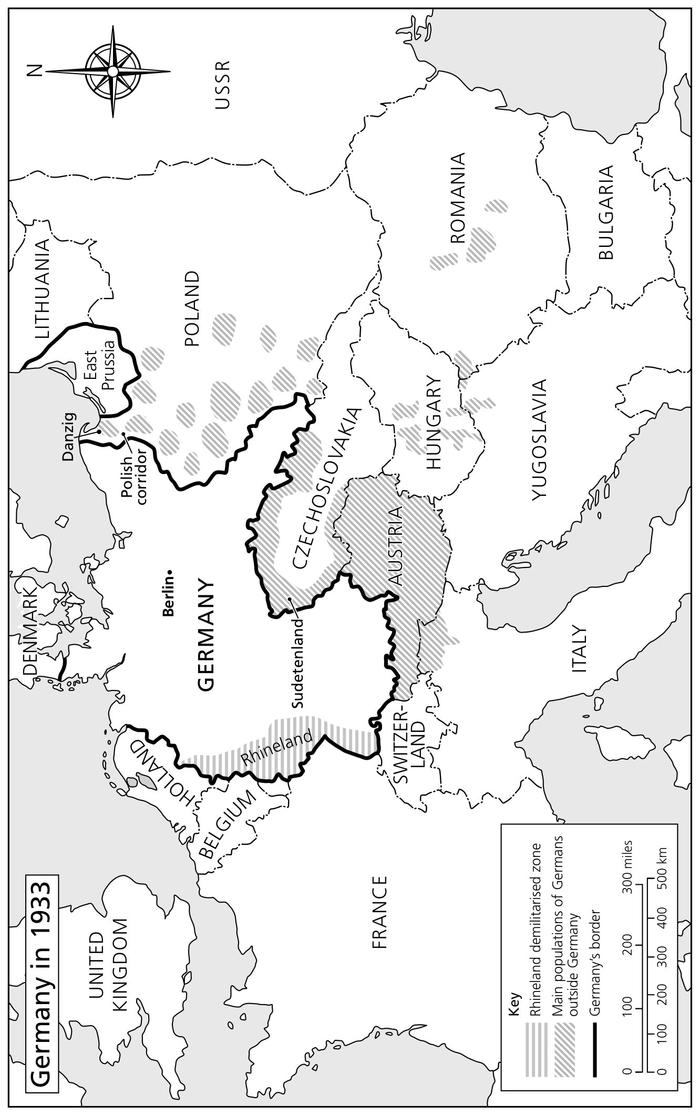

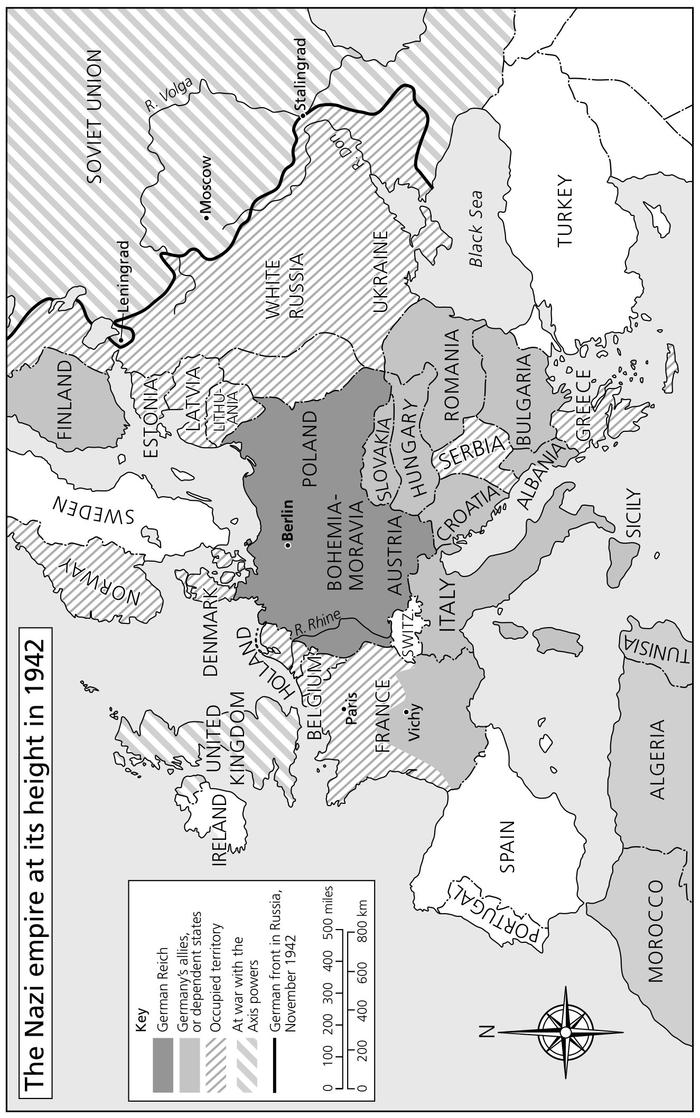

In 1919, one of the DAPs meetings was attended by an obscure army corporal of Austrian origin Adolf Hitler. Drexler gave Hitler a pamphlet entitled My Political Awakening and, according to Hitlers later thoughts expressed in his own political biography, Mein Kampf (My Struggle), Drexlers pamphlet reflected many of Hitlers own emerging beliefs. As a result, Hitler decided to join Drexlers tiny party and, by 1920, his rhetorical skills were both drawing in the crowds and overshadowing Drexler. That same year, he persuaded Drexler to change the partys name to the National Socialist German Workers Party (the NSDAP, or Nazis). In 1921, Drexlers leadership was challenged by Hitler and, after a brief resistance, Drexler resigned. Without the skills or organization to resist Hitler, Drexler left the NSDAP in 1923 and was a largely forgotten figure by the time he died in Munich in February 1942. By that time the party that Hitler had hijacked had been in power for almost ten years and had unleashed a world war of unbelievable savagery. German troops occupied Europe from the Atlantic to southern Russia and the mass killing of Jews in Eastern Europe had been taking place since the previous summer. That would have been impossible to imagine in the years immediately following Germanys defeat in 1918, but the roots of what Hitler would come to call the Third Reich went back deep into that

National defeat and the establishment of the Weimar Republic

As Germany faced defeat in November 1918 it was disintegrating. Sailors mutinied in the ports of Wilhelmshaven, Kiel and Hamburg; workers and ex-soldiers set up revolutionary