William Collins

An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

www.WilliamCollinsBooks.com

This eBook first published in Great Britain by William Collins in 2016

First published in the United States by Harper Books, an imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers, in 2016

Copyright 2016 by Robert K. Wittman and David Kinney

Robert K. Wittman and David Kinney assert the moral right to be identified as the authors of this work

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

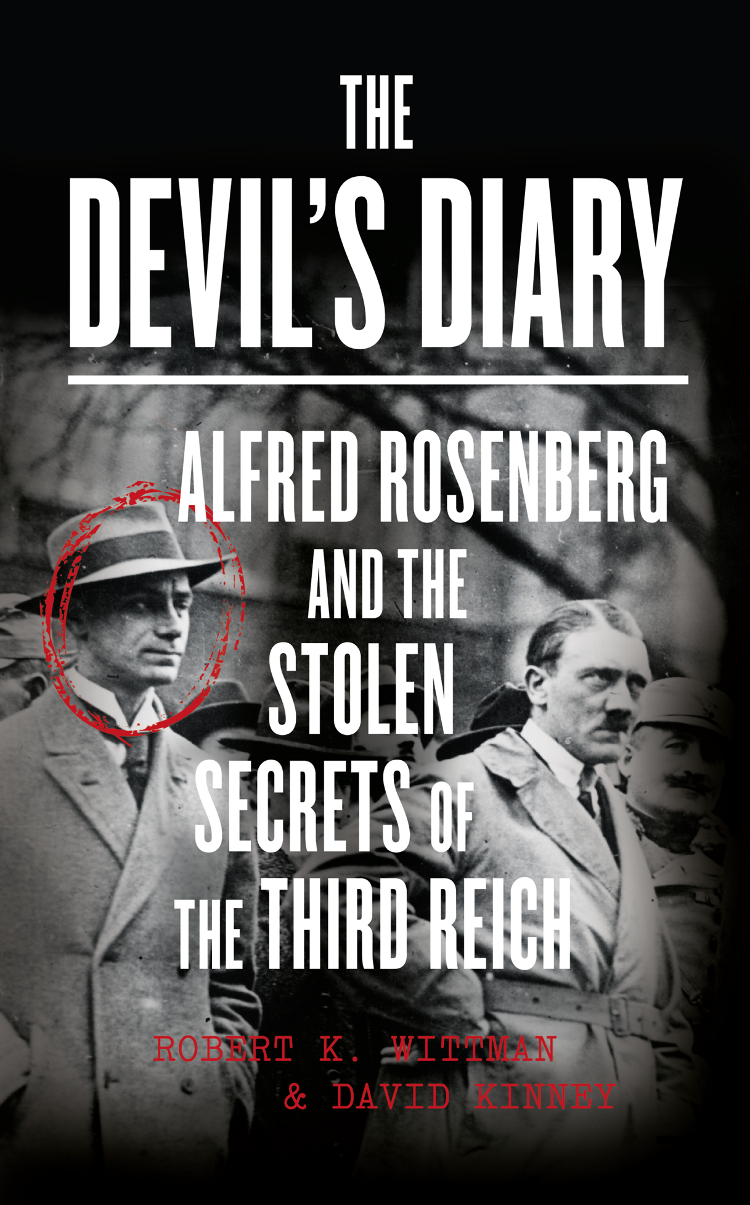

Cover photographs Keystone/Getty Images

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins

Source ISBN: 9780007575602

Ebook Edition March 2016 ISBN: 9780007575619

Version: 2016-03-08

For our families

Great philosophical changes need many generations to turn them into pulsating life. And even our present acres of death will someday bloom again.

ALFRED ROSENBERG

With small steps you can stumble into mass murders, thats the bad part. Very small steps are sufficient.

ROBERT KEMPNER

Contents

Long live eternal Germany! Local Nazis welcome Alfred Rosenberg (center, hand raised) to Heiligenstadt, Thuringia, in 1935. (ullstein bild/ullstein bild via Getty Images)

T he palace on the mountain loomed over a stretch of rolling Bavarian countryside so lovely it was known as GottesgartenGods Garden.

From the villages and farmsteads on the meandering river below, Schloss Banz commanded attention. Its sprawling stone wings glowed a luminous gold in the sunlight, and a pair of delicately tapered copper spires rose high above its Baroque church. The site had a thousand-year history: as a trading post, as a castle fortified to withstand armies, as a Benedictine monastery. It had been pillaged and destroyed in war, and extravagantly rebuilt for the royal Wittelsbach family. Kings and dukes, and once even Kaiser Wilhelm II, the last emperor of Germany, had graced its opulent halls. Now, in the spring of 1945, the colossus was an outpost of a notorious task force that had spent the war looting occupied Europe for the glory of the Third Reich.

As defeat drew near following six punishing years of war, Nazis all across Germany had been burning sensitive government files before the documents could be seized and used against them. But bureaucrats who could not bring themselves to destroy their papers instead hid them in forests, in mines, in castles, and in palaces like this one. Around the country, immense libraries of secrets were there for the Allies to find: detailed internal records shedding light on the warped German bureaucracy, on the militarys pitiless war strategy, and on the obsessive Nazi plan to clear Europe of its undesirable elements, finally and forever.

In the second week of April, the soldiers of General George S. Pattons Third U.S. Army and General Alexander Patchs Seventh U.S. Army overran the region. Since crossing the Rhine a few weeks earlier, the men had , slowed only by demolished bridges, improvised roadblocks, and pockets of stubborn resistance. They passed cities flattened by Allied bombs. They passed hollow-eyed villagers and houses flying not the Nazi swastika but white sheets and pillowcases. The German army had all but disintegrated. Hitler could be dead in three and a half weeks.

Not long after the Americans arrived in the region, they encountered a flamboyant aristocrat who wore a monocle and high, polished boots. Kurt von Behr had plundering private art collections and ransacking common household furnishings from tens of thousands of Jewish properties in France, Belgium, and the Netherlands. Just before the liberation of Paris, he and his wife fled to Banz with loads of pilfered treasure in a convoy of eleven cars and four moving vans.

Now von Behr wanted to cut a deal.

He went to the nearby town of Lichtenfels and approached a military government officer named Samuel Haber. It seemed that von Behr beneath the elaborately painted ceilings of the palace. If Haber would give him permission to stay put, von Behr would show him a secret stash of important Nazi papers.

dedicated to the task. In April alone, its target teams would capture thirty tons of Nazi files.

Acting on von Behrs tip, the Americans made their way up the mountain and through the gates to the palace to see von Behr. The Nazi escorted them five stories belowground, where, sealed behind a false wall of concrete, a mother lode of confidential Nazi documents was hidden. The files filled an enormous vault. What could not fit inside lay scattered about the room in piles.

After surrendering his secret, von Behrapparently realizing that his gambit would not save him from the ravages of Germanys humiliating defeatprepared to depart the stage in style. He donned one of his extravagant uniforms and accompanied his wife to their bedroom in the estate. Raising two flutes of French champagne laced with cyanide, they toasted the end of everything. The episode, an American correspondent wrote, had all the elements of the melodrama Nazi leaders seemed to relish.

Soldiers found von Behr and his wife slumped in their luxurious surroundings. As they examined the bodies, they spied the half-empty bottle still sitting on the table.

The couple had chosen : 1918, the year their beloved homeland had been laid low at the end of another world war.

The papers in the vault belonged to Alfred Rosenberg, Hitlers chief ideologue and an early member of the Nazi Party. Rosenberg was a witness to the partys embryonic days in 1919, when bitterly angry German nationalists discovered a leader in Adolf Hitler, the bombastic, vagabond veteran of the First World War. In November 1923, on the night Hitler tried to overthrow the Bavarian government, Rosenberg marched into the Munich beer hall one step behind his hero. He was there in Berlin a decade later when the party came to power and set about crushing its enemies. He was there in the arena, fighting, as the Nazis remodeled all of Germany in their image. He was there to the end, when the war turned and the whole twisted vision fell apart.

In the spring of 1945, as investigators began leafing through the enormous cache of documentswhich included 250 volumes of official and personal correspondencethey discovered something remarkable: Rosenbergs personal diary.

The account was written by hand across five hundred pages, some entries in a bound notebook, more on loose sheets. It began in 1934, a year into Hitlers rule, and ended a decade later, a few months before the war ended. Of the most important men in the highest ranks of the Third Reich, only Rosenberg, Propaganda Minister Joseph Goebbels, and Hans Frank, the brutal governor-general of occupied Poland, . The others, Hitler included, took their secrets with them to their graves. Rosenbergs diary promised to shed light on the workings of the Third Reich from the perspective of a man who had operated at the very upper reaches of the Nazi Party for a quarter of a century.