I am grateful to the Hewson family for allowing me to reproduce the photographs of Rothay Reynolds, his parents and siblings. Also included are three photographs taken by Anthony Hewson in 1938 during his visit to Reynolds in Berlin. All photos appear by permission of the Hewson family unless the source is otherwise mentioned.

For providing information about events, none were better placed than newspaper correspondents. Wherever was excitement, there were they. They raced about the world in search of what was most urgent, most timely; interviewed the great, and witnessed the stuff of headlines. Inside information was at their disposal, and on their typewriters they played each days tumult. Like bloodhounds following a scent, they carried news, a ravening pack. Trains, aeroplanes, motor-cars, carried them to the scene of all disasters; war and rumours of wars set them in motion.

T HE T HIRTIES , M ALCOLM M UGGERIDGE

T he 1930s has been described as the golden age of newspapers in Great Britain. In a world before television, with radio in its infancy, newspapers were the predominant means by which everyday men and women could learn news of the outside world. Newspapers were more trusted than they are now (whether or not that trust was justified is a separate question). There were scores of them in 1938 fifty-two morning, eighty-five evening and eighteen Sunday newspapers were printed in the United Kingdom. In deciding which newspapers to focus on, this book follows the lead of Frank Gannon, whose 1971 study The British Press and Germany, 19361939 prioritises what he calls the major newspapers. These comprised seven national dailies, two important Sunday papers and the Manchester Guardian, which had an influence and reach far beyond its status as a regional paper. A short guide to the ten titles, which are listed below, follows at the end of the book.

Daily Express

Daily Herald

Daily Mail

Daily Telegraph

Manchester Guardian

Morning Post

News Chronicle

The Observer

Sunday Times

The Times

A mass of dramatis personae feature in the narrative that follows. But at the heart of this story are the unique band of men and women who, like Rothay Reynolds, were working for British newspapers in Europe. What these correspondents experienced in Berlin and other continental cities, and the resulting dispatches they sent back to London, are of prime importance. This is a short guide to their roles.

Vernon Bartlett: News Chronicle correspondent, roving role.

Paul Bretherton: Daily Mail correspondent, roving role.

Harold Cardozo: Daily Mail correspondent in Paris.

Ian Colvin: Morning Post and later News Chronicle correspondent.

Sefton Tom Delmer: Daily Express chief foreign correspondent.

Norman Ebbutt: The Times correspondent in Berlin.

Eric Gedye: Daily Telegraph correspondent in Vienna, later New York Times.

Shiela Grant Duff: Observer correspondent during Saar plebiscite.

Hugh Carleton Greene: Daily Telegraph assistant and later correspondent in Berlin.

H. D. Harrison: News Chronicle correspondent in Belgrade, later Berlin.

James Holburn: Times assistant and then correspondent in Berlin.

Ralph Izzard: Daily Mail assistant in Berlin, later Germany bureau chief.

Wallace King: Daily Herald correspondent in Berlin.

Charles Lambert: Manchester Guardian correspondent in Berlin.

Iverach McDonald: Times reporter in Berlin and elsewhere.

Noel Monks: Daily Express journalist in Berlin and elsewhere.

H. H. Munro (Saki): Morning Post foreign correspondent.

Noel Panter: Daily Telegraph Munich correspondent.

Selkirk Panton: Daily Express reporter in Vienna and Berlin.

G. Ward Price: Daily Mails chief foreign correspondent.

Douglas Reed: Times correspondent in Vienna, later joined News Chronicle.

Rothay Reynolds: Daily News correspondent in St Petersburg, Daily Mail Berlin bureau chief, Daily Telegraph Rome correspondent.

Karl Robson: Morning Post correspondent in Berlin.

John Segrue: News Chronicle correspondent in Berlin.

Philip Pembroke Stephens: Daily Express correspondent in Berlin.

Frederick Voigt: Manchester Guardian correspondent in Berlin, then Paris, then diplomatic correspondent.

Eustace Wareing: Daily Telegraph correspondent in Berlin.

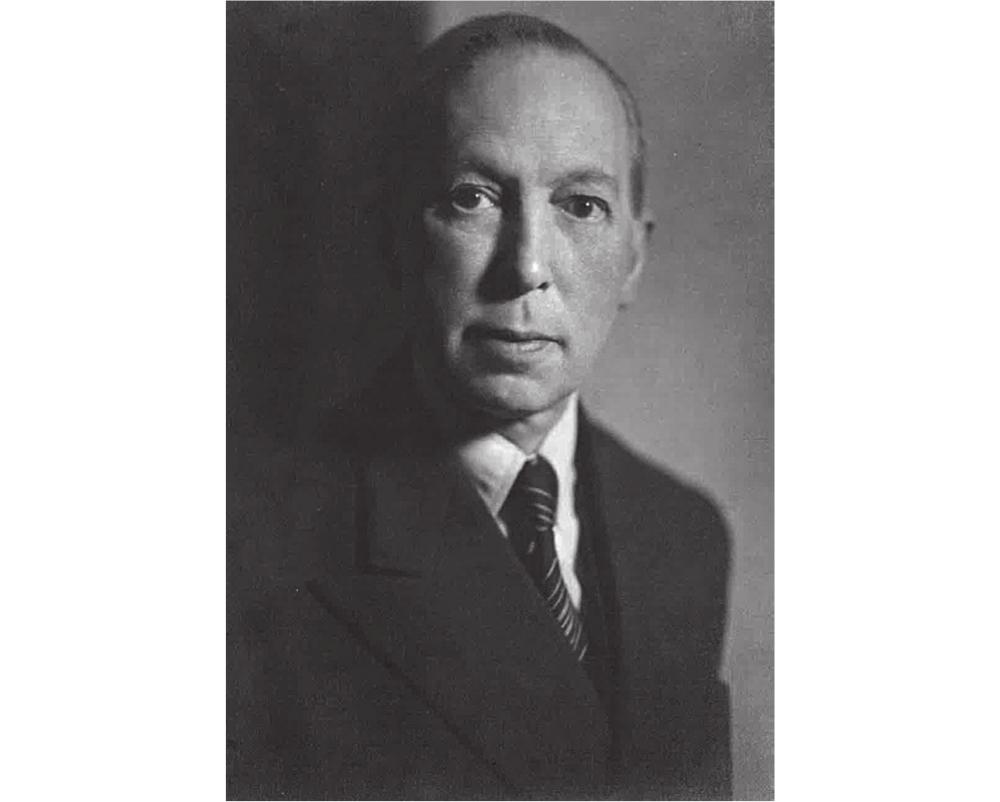

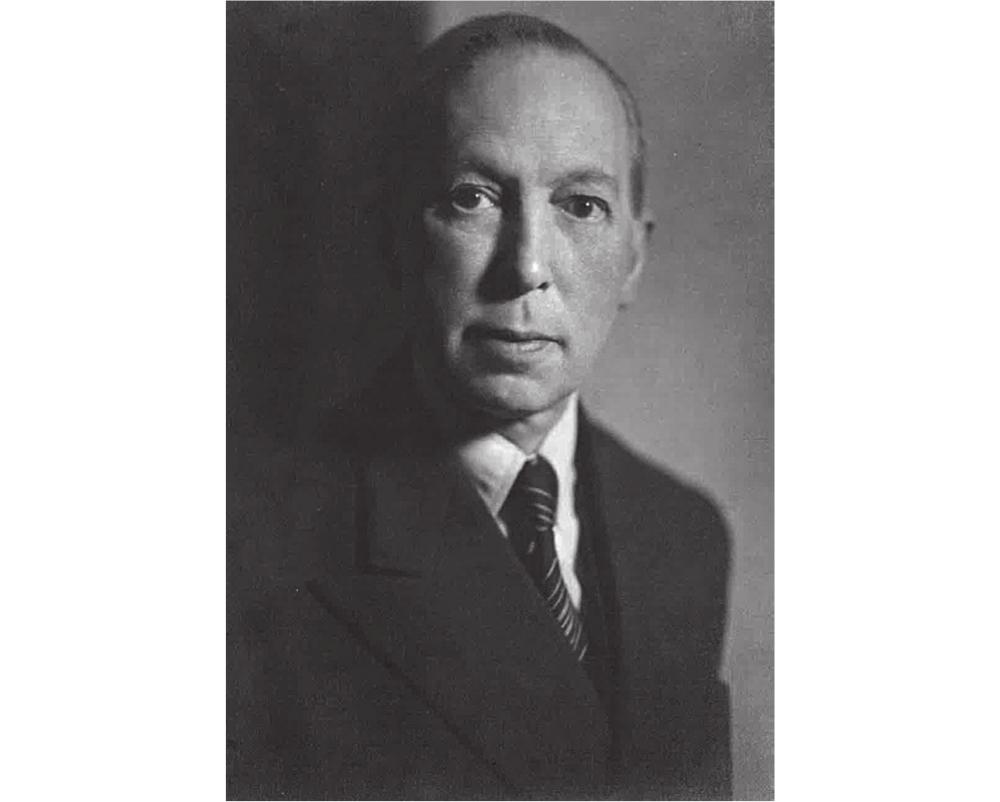

Photo portrait of Rothay Reynolds, late 1930s.

I t was high summer in Jerusalem and growing uncomfortably hot for the small congregation gathered at the church. Many in attendance were English and unused to such heat, even after living in the city for several years. It was August 1940 and Britains League of Nations mandate to govern Palestine had been in force for two decades. Almost a year into a new war with Germany, minds drifted increasingly to friends and relatives at home. Palestines future remained a headache for leaders in London, who regarded it as a distraction during a tumultuous period. But the British mandate remained, forcing them to stay.

The metal cross at the altar was too hot to touch; even the ancient stone walls had warmth. A dress code of formal wear made matters worse in the heat and the handful present shifted uneasily in their pews. Oddly, they were at the church for the funeral of a man they had met just weeks before. Among them was the chief surgeon at the government hospital, who had not been able to save him. A group of British nurses had sent a wreath of flowers.

It was the funeral of a 67-year-old Englishman named Rothay Reynolds. He would not have come to Jerusalem had it not been for the war one of the many individuals displaced amid the chaos. For reasons few of them knew, Reynolds had made the long and hard journey from Italy, an exhausting month-long trip that took its toll on his health. He was in a weak state when he arrived in the ancient city, and it worsened when he contracted malaria. A few days later he caught pneumonia and finally succumbed.

A door creaked slowly open and Reynoldss coffin came forward, draped in the Union flag. British military police acted as pall-bearers and bore him to the front of the church for a service officiated by a Franciscan friar in a flowing brown tunic. It was a fittingly sacred end for Reynolds who, in his younger years, had been ordained an Anglican priest before converting to Catholicism. He is the sort of person who would be glad to die in Jerusalem, wrote a friend back in Britain. After the service he was laid to rest in the Roman Catholic cemetery on the side of Mount Zion. In fact, one cant feel sorry for him in any way; his life was so full and so good, the friend said. One can only feel sorry that one will never see him again.

But who was he? The congregation in Jerusalem had dutifully given Reynolds a fine send-off, despite not knowing much about him. It was a typically English act in honour of a man who had ventured into their quasi-outpost of the British Empire and met his end. The people who knew him, relatives and friends at home, were forced to mourn his passing from afar. The congregation guessed Reynolds was an interesting man to travel as far as Jerusalem in the middle of a new world war was no easy feat but they had little inkling of his startling background.