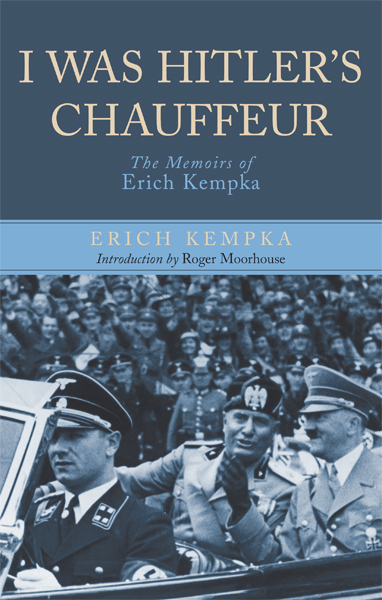

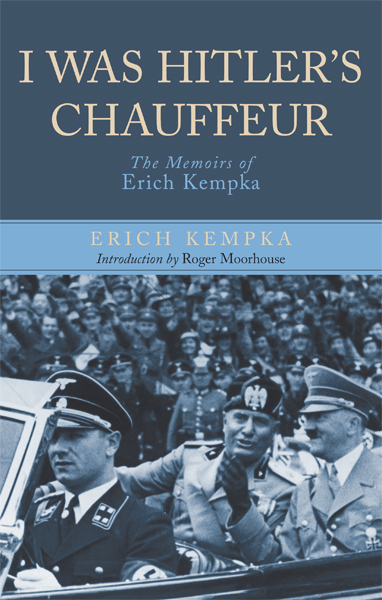

I Was Hitlers Chauffeur

I have portrayed the events related in this book

to the best of my knowledge and conscience. I have omitted

nothing and inserted nothing, but have portrayed the

historical facts as I personally experienced them.

Erich Kempka

Erich Kempka (19101975)

Original German edition: Ich Habe Adolf Hitler Verbrannt

1951 by Kyrburg, Munich, Germany

First published in Great Britain in 2010

Reprinted in this format in 2012 by

Frontline Books

an imprint of

Pen & Sword Books Ltd

47 Church Street

Barnsley

South Yorkshire

S70 2AS

Copyright Deutsche Verlagsgesellschaft mbH, 1991

English translation copyright Pen & Sword Books Ltd, 2010

Introduction Pen & Sword Books Ltd, 2010

ISBN 978 1 84832 630 9

eISBN 9781781599723

Erich Kempkas memoir was first published by Kyrburg (Munich) in 1951 and was entitled Ich Habe Adolf Hitler Verbrannt (I Cremated Adolf Hitler). In 1975, the memoir was re-issued by K.W. Schutz Verlag as Die Letzen Tage Mit Adolf Hitler (The Last Days With Adolf Hitler), with extra material by Erich Kern. It was reprinted in 1991 and 2004 by Deutsche Berlagsgesellschaft GmbH (Preussisch Oldendorf). I Was Hitlers Chauffeur is the first English-language translation of the expanded edition, and it includes a revised plate section and a new introduction by Roger Moorhouse. This is the first English language paperback edition.

A CIP catalogue record for this book is

available from the British Library

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission from the Publisher in writing.

For a complete list of Pen & Sword titles please contact

PEN & SWORD BOOKS LIMITED

47 Church Street, Barnsley, South Yorkshire, S70 2AS, England

E-mail: enquiries@pen-and-sword.co.uk

Website: www.pen-and-sword.co.uk

Contents

Plates

Frontispiece: Erich Kempka

Introduction

E RICH K EMPKA WAS ONE of those silent witnesses who is easily forgotten or overlooked by historians. Born in 1910 in the industrial city of Oberhausen in the Ruhr, he grew up in humble circumstances as one of ten children born to a family descended from Polish immigrants. As a young man, he served an apprenticeship with the DKW vehicle distributors in nearby Essen, before finding a job as a driver for a local newspaper. In those early days of the motor car, it was a choice of career that would serve him well and would propel him to the very heart of coming events.

Already a Nazi party member from 1930, Kempka served as chauffeur to the partys regional leader or Gauleiter in Essen, Josef Terboven. Early in 1932, he was recommended by Terboven as a reserve driver for Adolf Hitlers personal motor pool. Accepted for that post, he would also be named as one of the eight original members of Hitlers bodyguard the SS-Begleitkommando.

As Hitlers chauffeur, Kempka journeyed right across Germany. Indeed, as he related, his first action after his appointment was to jump into the Fhrers six-litre Mercedes and drive the 480 or so kilometres from Munich to Berlin. During the election campaigns of 1932 the last year of the Weimar Republic Kempka accompanied Hitler everywhere, covering an astonishing 132,000 kilometres in crisscrossing the country to meet Hitlers plane and deliver him to his various speaking engagements. At other times, he recalled, there was a more relaxed atmosphere, as Hitler ever the enthusiast for the motorcar would sit alongside him, chatting easily and mapreading with a road atlas spread across his knees. The connection thus forged would be the defining relationship of Kempkas life. He developed a strong personal bond with Hitler, which, it seems, was reciprocated. Kempka would be a constant companion, faithful servant and close confidante to Hitler for the next thirteen years, until the collapse of the Third Reich.

From this vantage point, Kempka was naturally well placed to observe Hitler at close quarters and to pass comment, not only on his masters foibles but also on those of many of the individuals that made up Hitlers inner circle, including his private secretary Martin Bormann and his personal physician Dr Theodor Morell. He was also one of the few Germans of that era who were well acquainted with Hitlers long-term mistress Eva Braun. Indeed, it would be Kempka who insisted on carrying Eva Brauns body up from the Reich Chancellery bunker on 30 April 1945, prior to its cremation in what remained of the Chancellery garden.

Kempka was also well placed to comment on other salient events of the Third Reich. Its a funny thing, the American prosecutor said of Kempka at Nuremberg, that you happened to be everywhere. He was present, for instance, at the so-called Night of the Long Knives, when SA-leader Ernst Rhm and many of his fellows were murdered. Yet, his focus in this book was very much on events at the very end of the war, specifically the circumstances of Hitlers death and his own remarkable escape from the bunker and from Berlin.

It was in this capacity, indeed, that Kempka was to come to the attention of the world. At the Nuremberg Tribunal in the summer of 1946, Erich Kempka took the stand as an eyewitness of those tempestuous last days of the Third Reich. He was called, in the first instance, in the trial in absentia of Martin Bormann, whose defence attorney chose the unusual tactic of arguing that his client could not be charged as he had been killed in the battle for Berlin the previous year. In his rather breathless testimony before the tribunal, Kempka claimed to have been one of the last people to have seen Bormann alive, and vividly described the circumstances of the Soviet attack in which the former Reichsleiter was thought to have perished. Despite Kempkas evidence, however, the myth of Bormanns survival would persist for more than two decades, spawning numerous unconfirmed sightings in Latin America, until his remains were finally discovered not far from where Kempka had last seen him in 1972.

Of course, Kempka would also serve as a witness to another high-profile death. Though he had not seen Hitlers death itself, he was nonetheless present in the immediate aftermath and was to be intimately involved in the circumstances surrounding Hitlers cremation. That afternoon, he was contacted by Hitlers adjutant Otto Gnsche, who demanded that he bring 200 litres of fuel from his motor pool to the Reich Chancellery garden. Though he did not know it at the time, that fuel was to be used to cremate the bodies of Adolf Hitler and Eva Braun. Kempka would be one of the small group, who stood that afternoon and watched the two bodies burn.

Naturally, perhaps, this moment was to be one of those that rather defined Kempkas life. Accordingly, his memoirs, first published in German in 1951, originally carried the sensational title Ich Habe Adolf Hitler Verbrannt (I Cremated Adolf Hitler), before being toned down somewhat for a 1975 reissue as The Last Days with Adolf Hitler. That later edition also contained an accompanying text by one Erich Kern, who was himself a veteran of the SS-Leibstandarte and, by the 1970s, was an extremist, right-wing journalist, with some rather dubious connections. Kerns text, which was billed as providing background and context to Kempkas memoir, was in fact more of an extended and intemperate rant, which railed against the Western Allies and against a generation of historians that according to Kern had peddled lies and distortions about Hitler and the Nazi regime.

Next page