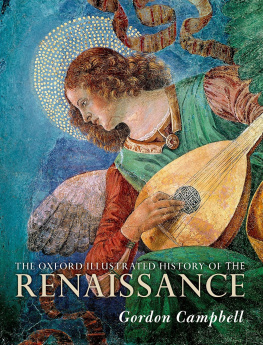

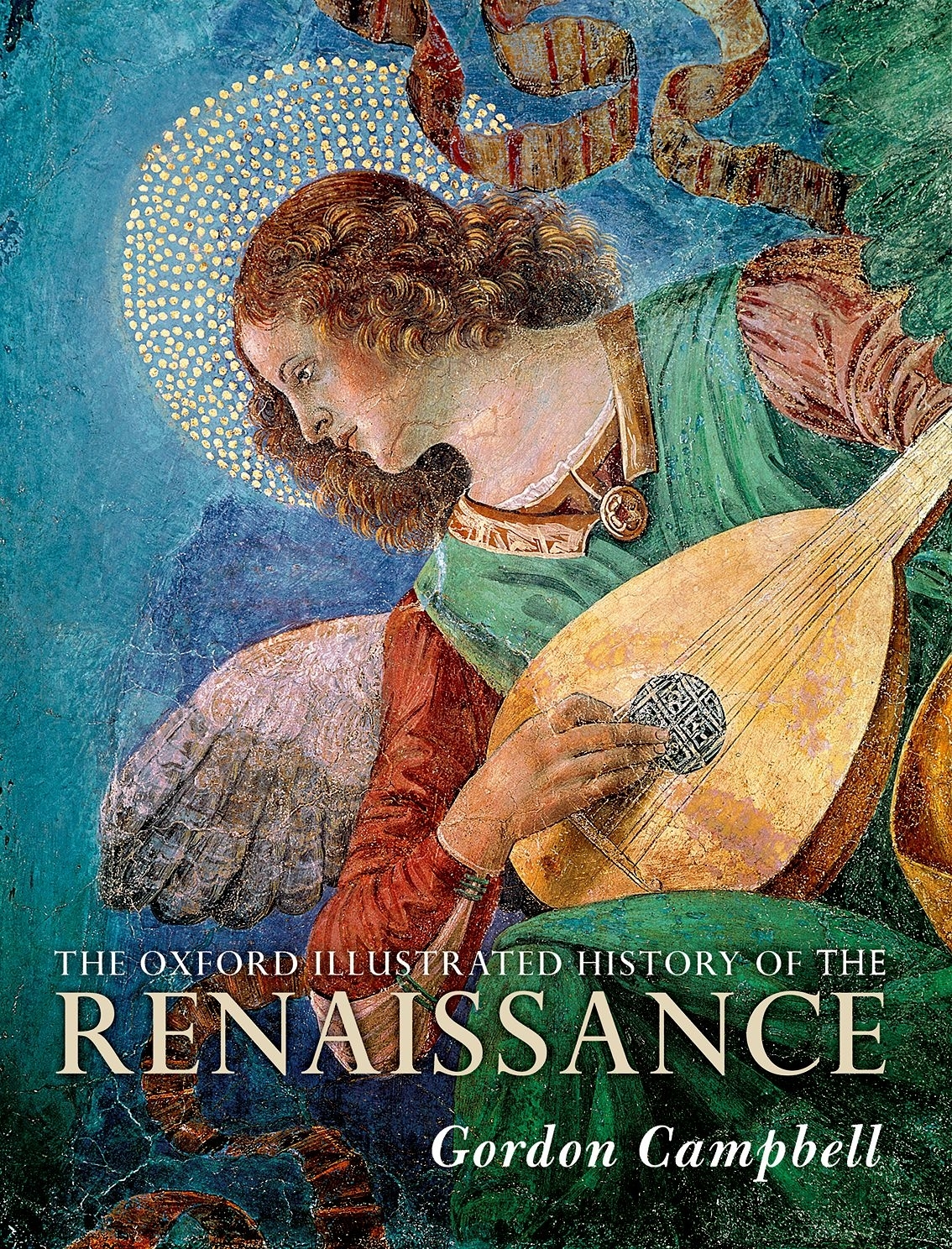

The Oxford Illustrated History of

the Renaissance

The historians who contributed to The Oxford Illustrated History of the Renaissance are all distinguished authorities in their field. They are:

FRANCIS AMES-LEWISBirkbeck, University of London

WARREN BOUTCHERQueen Mary University of London

PETER BURKEUniversity of Cambridge

GORDON CAMPBELLUniversity of Leicester

FELIPE FERNNDEZ-ARMESTOUniversity of Notre Dame

PAULA FINDLENStanford University

STELLA FLETCHERUniversity of Warwick

PAMELA O. LONGIndependent scholar

MARGARET M. M c GOWANUniversity of Sussex

PETER MACKUniversity of Warwick

ANDREW MORRALLBard Graduate Center

PAULA NUTTALLVictoria and Albert Museum

DAVID PARROTTUniversity of Oxford

FRANOIS QUIVIGERThe Warburg Institute

RICHARD WILLIAMSRoyal Collection Trust

The editor and contributors wish to dedicate this volume to Matthew Cotton.

Great Clarendon Street, Oxford, ox 2 6 dp , United Kingdom

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the Universitys objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide. Oxford is a registered trade mark of Oxford University Press in the UK and in certain other countries

Oxford University Press 2019

The moral rights of the authors have been asserted

First Edition published in 2019

Impression: 1

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of Oxford University Press, or as expressly permitted by law, by licence or under terms agreed with the appropriate reprographics rights organization. Enquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope of the above should be sent to the Rights Department, Oxford University Press, at the address above

You must not circulate this work in any other form and you must impose this same condition on any acquirer

Published in the United States of America by Oxford University Press 198 Madison Avenue, New York, NY 10016, United States of America

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

Data available

Library of Congress Control Number: 2018939297

ISBN 9780198716150

ebook ISBN 9780191025259

Printed in Italy by L.E.G.O. S.p.A. Lavis (TN)

Links to third party websites are provided by Oxford in good faith and for information only. Oxford disclaims any responsibility for the materials contained in any third party website referenced in this work.

Contents

Introduction

Gordon Campbell

Humanism and the Classical Tradition

Peter Mack

War and the State, c.1400c.1650

David Parrott

Religion

Stella Fletcher

The Civilization of the Renaissance

Franois Quiviger

Art and Architecture in Italy and Beyond

Francis Ames-Lewis

Art and Architecture in Flanders and Beyond

Paula Nuttall and Richard Williams

The Performing Arts: Festival, Music, Drama, Dance

Margaret M. McGowan

Vernacular Literature

Warren Boutcher

Craft and Technology in Renaissance Europe

Pamela O. Long and Andrew Morrall

The Renaissance of Science

Paula Findlen

The Global Renaissance

Felipe Fernndez-Armesto and Peter Burke

T he Renaissance is a model of cultural descent in which the culture of fifteenth- and sixteenth-century Europe is represented as a repudiation of a medieval world in decline in favour of the revival of the culture of ancient Greece and Rome. The parallel religious model is the Reformation, in which the church is represented as turning its back on corruption and decline in favour of a renewal of the purity of the early church. In both models, there had to be an intervening middle period between the glorious past and its revival. The idea of the Middle Ages (medium aevum) was introduced to European historiography by the Roman historian Flavio Biondo in 1437, and quickly became a commonplace. Thereafter European history was conventionally divided into three periods: classical antiquity, the Middle Ages, and the modern period. The biblical metaphor of rebirth was first applied to art by Giorgio Vasari, who used the term to denote the period from Cimabue and Giotto to his own time. It was certainly an inordinately slow birth.

The broadening of the term renaissance to encompass a period and a cultural model is a product of the nineteenth century, albeit with roots in the French Enlightenment. That is why we use the French form (renaissance) rather than the Italian (rinascit) to denote this rebirth. In 1855 the French historian Jules Michelet used the term Renaissance as the title of a volume on sixteenth-century France. Five years later Jacob Burckhardt published Die Cultur der Renaissance in Italien (The Civilization of the Renaissance in Italy), in which he identified the idea of a Renaissance with a set of cultural concepts, such as individualism and the idea of the universal man. Vasaris designation of a movement in art had become the term for an epoch in history associated with a particular set of cultural values. These issues are explored in detail in Franois Quivigers chapter on The Civilization of the Renaissance, which explores the afterlife of Burckhardts concept of individuality in more recent notions of self-fashioning and gender fluidity, and in the complex notion of the self.

The model of the Renaissance has evolved over time. An older generation of historians had a predilection for precision: the Middle Ages were deemed to have begun in 476 with the fall of the Roman Empire in the West and concluded with the fall of Constantinople in 1453, when Greek scholars fled to Italy with classical manuscripts under their arms. This book subverts those easy assumptions at every turn, but the contributors nonetheless assume that the model of a cultural Renaissance remains a useful prism through which the period can be examined. That model has been challenged by those who prefer to think of the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries purely in terms of a temporal period called the Early Modern period. This idea is, of course, as fraught with ideological baggage as is the term Renaissance, and embodies narrow assumptions about cultural origins that may be deemed inappropriate in a multicultural Europe and a globalized world.

This is a book about the cultural model of a Renaissance rather than a period. That said, it must be acknowledged that while this model remains serviceable, it also has limitations. The idea of a Renaissance is of considerable use when referring to the scholarly, courtly, and even military cultures of the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries, because members of those elites were consciously emulating classical antiquity, but it is of little value as a model for popular culture and the everyday life of most Europeans. The idea of historical periods, which is emphasized by the use of centuries or rulers as boundaries, is particularly problematical in the case of the Renaissance, because a model that assumes the repudiation of the immediate past is insufficiently attentive to cultural continuities.

Such continuities are sometimes not readily apparent, because they are occluded by Renaissance conventions. Shakespeare is a case in point. He was in many ways the inheritor of the traditions of medieval English drama, and he accordingly divided his plays into scenes. Printed conventions, however, had been influenced by the classical conventions in Renaissance printing culture. Horace had said that plays should consist of neither more nor less than five acts (Neue minor neu sit quinto productior actu fabula,