My lifelong interest in history led me to discover archery in the early 1990s. This book emerged from the combination of these two pursuits. I have known many archers over the years who have been generous with their time and opinions. Brian Annetts, Trevor Green and the late Margaret Tyson gave me generous advice and encouragement when I started archery. Steve Stratton has endured my historical musings, and helped me to think more clearly on several issues. He and Mark Stretton also cheerfully donned their fifteenth-century garb to appear in this book. Pip Bickerstaffe asked some of the questions which this book attempts to answer. Thanks to all my fellow archers, particularly the members of the Pickwicks Pepperpots.

My parents encouraged my study of history, particularly by supporting my postgraduate studies at Leeds University. Discussions with other history lovers have helped to keep the subject alive for me. Shaun Barrington and Tom Chidlaw of Spellmount have provided valuable advice from their experience as publishers. While researching the book the good humoured expertise of the staff at the Bodleian Library in Oxford made my task so much easier.

Finally, there is an incalculable debt to my family. My children provided a captive audience for historical storytelling at home and abroad. Eleanor has supported and encouraged me throughout the writing of this book without complaint and listened to me expound on medieval archery at all sorts of times. Grateful thanks to you all.

Contents

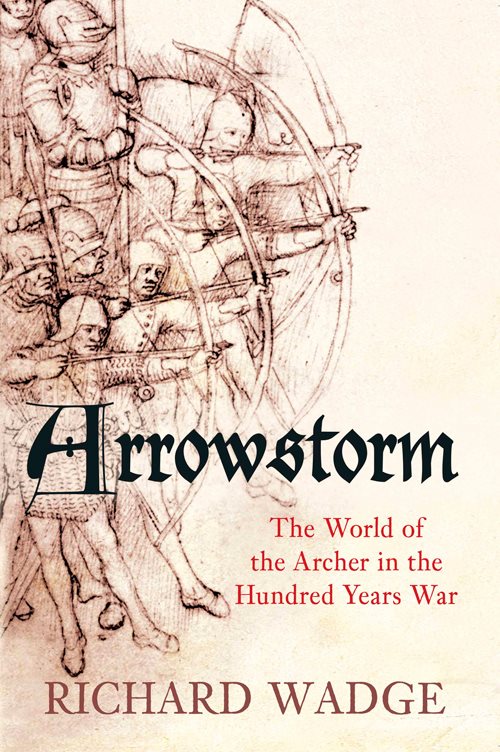

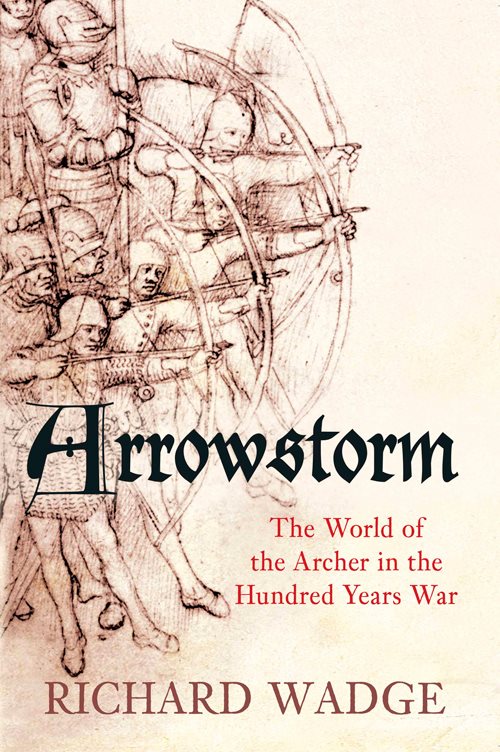

Stories of the triumphs of the medieval English archer are widely known; how the bluff, no-nonsense English yeoman defeated armies of arrogant, aristocratic enemies. While there is some truth and great drama in these stories, they do not give us any idea why these men spent countless hours over many years practising archery so that they could be part of the English armies in the later Middle Ages.

This book is a history of the people who were involved in medieval archery, either militarily or in allied economic and manufacturing activities between roughly 1300 and 1550. The actions of kings and nobles, the events of the great battles are a part of this; they provide a structure. But this is not a conventional military history, an account of strategy, campaigns and battles. It is in part a history of military logistics in the modern sense of organizing supplies, but the scope is wider than just military matters. The main focus is on the ordinary people and how and why they took part in the great events of their time. This is not a chronological history, but instead a series of studies of related topics, which build together to produce an outline of the world of the medieval English and Welsh archers, and the economic framework that supported archery at the time.

Before delving into the world of the medieval archer it is necessary to outline briefly the social and economic conditions of the period. Medieval men and women were not greatly different to us in many ways, except that they lived in a smaller world than we do. A holiday might have meant a trip to the nearest big town or city to enjoy the religious parades or plays, no farther. One great difference between their lives and ours was the immediacy of death. While medical care was more competent in the Middle Ages than we sometimes think, life was much more precarious, even without war or major pandemics. Another fundamental difference was that active religious belief, or at least practice, was universal. The imminence of death was not the only reason for devotion. Church attendance was compulsory, which helped to make religious practice an integral part of life.

This investigation will include an analysis of how willing men were to become soldiers, how many of the archers became professional soldiers, and what was in it for them. In part this is revealed by a consideration of how English armies were raised and organised. Unfortunately, there is no personal narrative by an archer of the period to rival, say, Benjamin Harriss account of being a rifleman in the Napoleonic wars, so we can only get a general picture of what motivated men to serve as archers. The one account that I am aware of is by Peter Bassett and Christopher Hanson, who both began as archers but later served as men at arms, and covers service between 1415 and 1429. This is fairly brief valuable since the authors were participants in the events themselves but it gives no insight into them as individuals and their feelings about military service. While it may not be possible to know the archers as individuals, it is possible to gain insights into their reasons for undertaking military service by looking at the opportunities and rewards available to them.

It is not just the ordinary people that we know little about as individuals; personal accounts of life in this period by noblemen and merchants are scarce. The chronicles of the churchmen provide vital, if not unbiased, narratives, but almost all of these give little consideration to the life and feelings of the ordinary people. The author of Gesta Henrici Quinti , a chaplain in the royal household, provides an important eyewitness account of the whole Agincourt campaign. While his purpose was to bear witness to the nobility and excellence of Henry V, he makes passing comments about the way he and others felt on the campaign, which gives a limited insight into the feelings of the archers. Because of this lack of personal accounts and a general lack of interest in the doings of ordinary men and women in the histories and chronicles, the main sources used must be administrative records. Occasionally, accounting records list rewards and pensions given to archers, which afford some clues to motivation. As well as records of the Royal household, there are customs and tax records, and administrative records of major cities such as London and York, which allow some understanding of local involvement in both war and the archery industry.

When a country makes a sustained military effort over several generations, as happened with England in the period of what we now call the Hundred Years War, an arms industry is born and grows. The second part of the book provides an account of the economic and manufacturing developments that underlay the military activity. It gives an idea of the dedicated trading networks that grew across Europe, as well as the economic developments within England that arose to meet the need for the regular supply of military archery equipment. This specialization was typical of the arms industries of Europe in the Middle Ages; though England developed an industry making the best military archery equipment in Western Europe using imported resources, but deliberately no export trade. The armourers of Milan and Southern Germany developed the reputation of producing the finest armour based on local raw materials, and exported their goods.

This sustained war effort put a strain on the economic and social development of England. Yet the mass of the population in the last quarter of the fourteenth century and most of the fifteenth century enjoyed a better quality of life. This seems paradoxical, when the English kings of the time were continually struggling to finance their wars. It has been estimated that in periods of heightened military activity the 1340s and from 1415 to the end of the 1420s perhaps 10% of the male population was directly involved in the war and an undetermined number of women and children were part of the supply industries, with the concomitant commitment of money and material. This level of investment of capital, materials and people must have been a problem in the decades after the major outbreaks of plague, when labour was at a premium.

Next page