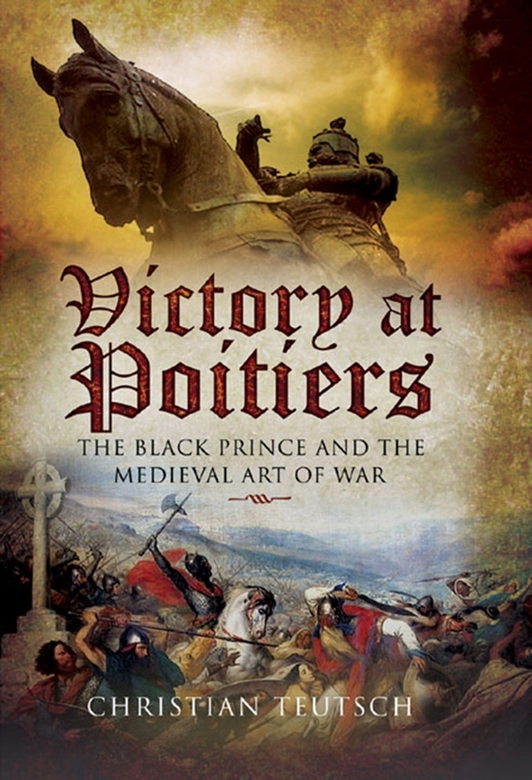

Other titles in the Campaign Chronicles series:

Napoleons Polish Gamble

Christopher Summerville

Armada 1588

John Barratt

Passchendaele

Martin Marix Evans

Attack on the Somme

Martin Pegler

Salerno

Angus Konstam

The Siege of Malta

David Williamson

The Battle of Borodino

Alexander Mikaberidze

Caesars Gallic Triumph

Peter Inker

The Battle of the River Plate

Richard Woodman

The German Offensives of 1918

Ian Passingham

The Viking Wars of Alfred the Great

Paul Hill

The Battle of North Cape

Angus Konstam

Dunkirk and the Fall of France

Geoffrey Stewart

Poland Betrayed

David Williamson

The Gas Attacks

John Lee

The Battle of the Berezina

Alexander Mikaberidze

First published in Great Britain in 2010 by

Pen & Sword Military

an imprint of

Pen & Sword Books Ltd

47 Church Street

Barnsley

South Yorkshire

S70 2AS

Copyright Christian Teutsch 2010

9781844685233

The right of Christian Teutsch to be identified as Author of this Work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission from the Publisher in writing.

Typeset in 11/13.5pt Garamond by

Mac Style, Beverley, East Yorkshire

Printed and bound in the UK by

CPI

Pen & Sword Books Ltd incorporates the imprints of Pen & Sword Aviation, Pen & Sword Maritime, Pen & Sword Military, Wharncliffe Local History, Pen and Sword Select, Pen and Sword Military Classics, Leo Cooper, Remember When, Seaforth Publishing and Frontline Publishing.

For a complete list of Pen & Sword titles please contact

PEN & SWORD BOOKS LIMITED

47 Church Street, Barnsley, South Yorkshire, S70 2AS, England

E-mail: enquiries@pen-and-sword.co.uk

Website: www.pen-and-sword.co.uk

Introduction

Now, sirs, though we be but a small company as in regard to the puissance of our enemies, let us not be abashed therefore; for the victory lieth not in the multitude of people, but whereas God will send it. If it fortune that the journey be ours, we shall be the most honoured people of all the world; and if we die in our right quarrel, I have the king my father and brethren, and also ye have good friends and kinsmen; these shall revenge us. Therefore, sirs, for Gods sake I require you do your devoirs this day; for if God be pleased and Saint George, this day ye shall see me a good knight.

Edward the Black Prince immediately

before Poitiers, as reported by Jean Froissart

E dward sat astride his riding horse, preserving his destrier for its designated rolethat moment in battle when the young prince might lead a heavy cavalry charge in all its glory against the fleeing French forces arrayed before him. But that was not how this battle would begin. The chronicler Geoffrey le Baker reports that as soon as scouts brought word that King Jean II had not only finally caught up with the English invasion force, but had formed his men into battle in anticipation of a fight, Edward dismounted and directed his fellow knights to do the same. Today the Black Prince would fight on foothis 6,000 against the French 14,000.

Edward, with the forces under his immediate command, was occupying a hillock on what now became the English left flank. Less than a half mile to his right front he could see the lead elements of the French assault, under Marshal Clermont, bursting through the thick hedgeline. This group of elite horsemen had seen the English forces consolidating and had determined to assault the English longbowmen to break up their lines and prevent them massing their fire and repeating that tactic that had so devastated the French mounted assaults on the field of Crcy-en-Ponthieu ten years before. However, the hedge served to disrupt the mounted charge, and as the Frenchmen broke through the few gaps, the prepositioned longbowmen fired at point-blank range. Froissart reports that they struck terror into the hearts of the French, for the rain of arrows was so continuous and so thick that the French did not know where to turn to avoid them.

But the battle was far from won. Arrows were not as effective against the next charge, led by Clermonts co-commander of the French vanguard, Marshal d Audrehem. His battalion, which attacked along a route parallel to Clermonts but barely a quarter mile from Edwards location, enjoyed much more success at first, but eventually it, too, fell victim to the superiority of the English missiles. Soon after, the second division of the French army, 4,000 dismounted men-at-arms under the command of the Dauphin, had crossed the fields and were aimed directly at the princes division, which had not yet been engaged. Behind the Dauphins division, out of sight due to the undulating terrainbut definitely not beyond the notice of Edwardwere the third and fourth French divisions, under the Duke of Orlans and King Jean II, respectively. These two units alone outnumbered the meagre English forces present, and included some of the most distinguished knights of the realm. And here was young Edward, outnumbered, backed against a river, several days march from friendly lines. Was this the fight that he had hoped for or was it one that (much to his dread) had been forced upon him?

What had brought the Black Prince to this point? Why had he invaded France? Why had he brought such a paltry force? Did he really want to face Jean in battle? And what did he ultimately hope to achieve? Observers and historians have wrestled with these questions for nearly seven centuries. While contemporaries overwhelmingly held the young tactician in the highest regard, in the modern age his critics have outnumbered his admirers, and have almost universally underestimated Edward as a military commander.

Far from being chased to Poitiers and forced into a battle, Edward had lured his fathers rival into this fight. His entire strategy for this campaign rested upon his ability to draw the French king into being the one to attack. He did not have enough menthe English never had enough mento face the French in a set-piece battle on even terms. But there was no need for Edward to seek such a fight now. He had driven his army through the heart of France, taken what he wanted, despoiled what he didnt, and lured the wearer of his fathers crown into a position where he would be compelled to attack the 6,000 English and Gascons or go home in disgrace.

Jean did not want to be the attackerto assume the tactical offenceany more than did Edward. While neither to this point had extensive command experience, each could draw upon sufficient examples from the recent past to have gained an appreciation of the inherent strength of tactical defence. Edward, in particular, learned from the English experience at Bannockburn in 1314, Halidon Hill in 1333, at both Crcy and Nevilles Cross in 1346, and at the siege of Calais in 13461347. From these campaigns he knew that: (1) reluctant armies could be brought to battle given the right incentive; (2) these battles were not only more likely to occur if the enemy trusted too heavily in his own weight of numbers, but that victory was more dependent upon tactical than numerical superiority; and, (3) that battle as the final arbiter could empower a kingdom of lesser economy and population to overcome a stronger rival.