Pagebreaks of the print version

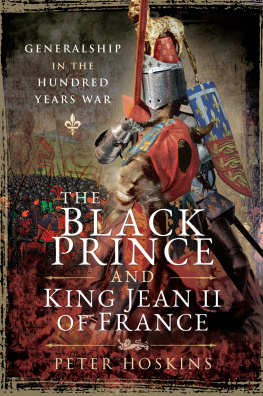

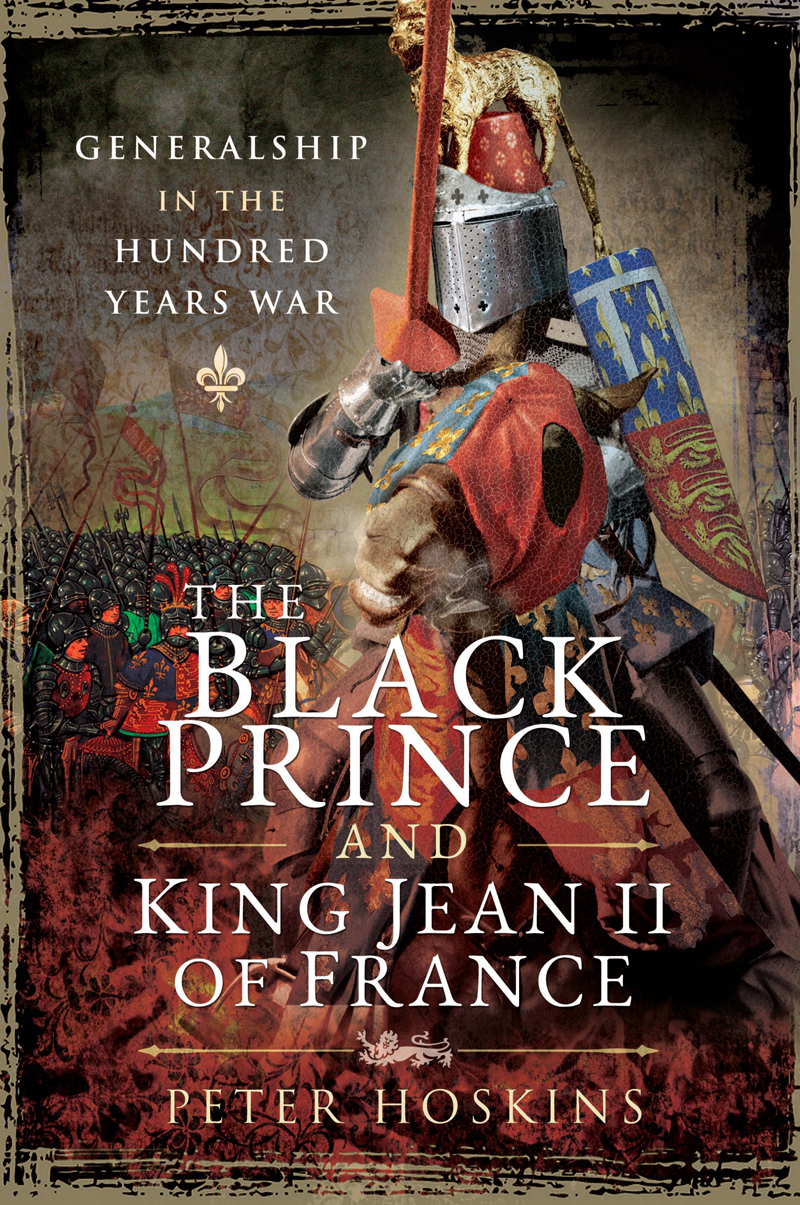

The Black Prince and King Jean II of France

The Black Prince and King Jean II of France

Generalship in the Hundred Years War

Peter Hoskins

First published in Great Britain in 2020 by

PEN & SWORD MILITARY

An imprint of Pen & Sword Books Ltd Yorkshire Philadelphia

Copyright # Peter Hoskins, 2020

ISBN 978-1-52674-987-1

eISBN 978-1-52674-988-8

Mobi ISBN 978-1-52674-989-5

The right of Peter Hoskins to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without

permission from the Publisher in writing.

Pen & Sword Books Ltd incorporates the Imprints of Aviation, Atlas, Family History, Fiction, Maritime, Military, Discovery, Politics, History, Archaeology, Select, Wharncliffe Local History, Wharncliffe True Crime, Military Classics, Wharncliffe Transport, Leo Cooper, The Praetorian Press, Remember When, White Owl, Seaforth Publishing and Frontline Publishing.

For a complete list of Pen & Sword titles please contact

PEN & SWORD BOOKS LTD

47 Church Street, Barnsley, South Yorkshire, S70 2AS, England

E-mail:

Website: www.pen-and-sword.co.uk

or

PEN & SWORD BOOKS

1950 Lawrence Rd, Havertown, PA 19083, USA

E-mail:

Website: www.penandswordbooks.com

For Grace and Sebastian

Preface

The idea for this comparative study came from an interview that I gave for a podcast on Jean II. My interviewer drew my attention to the lack of literature on Jean II in English. My first thought was a biography, but then I started to consider his career and life in the context of the Black Prince. Their careers ran in parallel for much of the first period of the Hundred Years War. However, while the Black Prince had a glittering military career, Jean left a less than glorious record in arms. Why should this English prince succeed when the king of the most powerful country in the medieval world failed so disastrously?

Jean is known best for his defeat by the Black Prince at Poitiers in 1356, but I began to appreciate that there was much more to this man than first meets the eye. He was quick of temper, headstrong and often arbitrary in his judgements, but he was a reformer and in many ways a man of principle, whatever his failures as a commander in the field. He was a man with considerable personal courage, hence the epithet le Bon attached to his name, which in the Middle Ages was a reflection of his acknowledged bravery rather than of any goodness in either his character or behaviour. In contrast, Edward of Woodstock, the Black Prince, seems to have been a man of cool judgement who fought and won two great battles, at a time when pitched battles were rare. These men had much in common: descent from King Philippe III of France, the French language, culture in the broad sense and the chivalric code. However, as I have already suggested above, there were many contrasts. Most notably, Edward was a future king from his birth but predeceased his father and never acceded to the throne, while when Jean was born none would have foreseen that he would become King of France.

In judging these men and their achievements we must also acknowledge that we are not comparing like with like. Edward, other than to a limited extent during his period as Prince of Aquitaine, did not have the broad responsibilities of a head of state. In modern parlance he was either a divisional or army commander in the field. Jean as Duke of Normandy before coming to the throne had similar limited responsibilities in the field, but as king he took on the broader responsibilities as head of state, commander-in-chief and chief of defence staff, all anachronisms of course, as well as a field commander. Thus, he had the challenges which Edward never faced of raising armies on a national scale, financing campaigns and bringing about reforms to redress deficiencies in French mobilisation and fighting tactics. In studying these men it must be remembered how young they were by modern standards for the responsibilities they held. Edward was only 16 at the Battle of Crcy and 26 when he won his great victory at Poitiers. He died just short of his 46th birthday. Jean, eleven years older than Edward, died just before his 45th birthday. He had also had considerable responsibility at a young age, being just 27 when he commanded the forces besieging Aiguillon. He became king at 31.

Acknowledgements

Thanks once again to Rupert Harding for his support for the idea which led to this book. My thanks are also due to Andrew Vallance and Linda Taylor for their review of the draft and for their helpful comments and suggestions.

List of Illustrations

FIGURES

The Valois Succession to the French Throne

MAPS

The Aiguillon Campaign, 1346

The Siege of Aiguillon, 1 April to 20 August 1346

The Black Princes Chevauche in the Languedoc, 1355

Crossing the Garonne and the Arige, 28 October 1355

Crossing the Garonne at Carbonne, 18 November 1355

Normandy and Breteuil, 1356

The Poitiers Chevauche , August to October 1356

The passage of Brantome, 810 August 1356

Crossing the Vienne, 14 August 1356

Romorantin to Poitiers

Battle of Poitiers Initial deployments and opening moves

Battle of Poitiers Attack of the vanguard

Battle of Poitiers Attacks of the Dauphins and the Duke of Orlans divisions

Battle of Poitiers The final phase

The Njera Campaign

The Battle of Njera

The Poitiers Battlefield

List of Plates

Edward the Black Prince as a Knight of the Garter.

The tomb of the Black Prince in Canterbury Cathedral.

Fourteenth-century portrait of Jean II by an unknown artist.

King Jean.

Franc cheval of Jean le Bon, 1360.

Vestiges of the ramparts of Aiguillon, dating back to Roman times.

Vestiges of Breteuil castle. It was built in the twelfth century by Henry II of England and demolished in 1378 after being retaken for the French by Bertrand du Guesclin.

The Battle of Poitiers: This photograph was taken after the driest summer for fifty years. The Miosson was little more than a minor stream but in wet weather it can be a much more significant river. The bridge replaced an earlier structure washed away by the river in flood in 1982. The land in the foreground would be susceptible to flooding in such conditions. Beyond the road on the right, where grass has not been planted, marsh plants are evident even in dry weather.

The Battle of Poitiers: Bakers broad deep valley, with the river Miosson in the middle-ground and the road running up the hill towards the princes position near the Croix de la Garde.

The Battle of Poitiers: This hedge has been allowed to grow to more than 3 metres, or 10 feet, in width. Such hedges would be formidable obstacles.

The Battle of Poitiers, as depicted in Froissart.

A reconstruction of a belfry, or siege tower, as favoured by Jean II, at Tiffauges castle.

The arms of war of the Black Prince. The white label of cadency, a horizontal bar with three downward points, differentiates the princes arms from those of his father and shows that he is the eldest son.