In a sense, this book is about fathers; their successes, failures, their influence and their legacies.This is dedicated, for all they have given me, to Alec Green, Stan Burr, Peter Coventry, John Tweedy Smith (and, of course, to my Mum). Contents

I should like to thank Michael Jones who first introduced me to Edward of Woodstock, and Alison McHardy and Tony Goodman who suggested how I might get to know him better. Tony put me in touch with Jonathan Reeve of Tempus to whom I am very grateful for his enthusiasm and support.

Claire Taylor and Simon Constantine have read parts of the typescript, improved many aspects of it and shaped more than they know thanks poppets. I am particularly grateful to Andrew Midgely for his help and professional expertise with many of the photographs and his remarkable willingness to head off to far-flung parts of the country in search of BP-related sites.

My thanks to the past, present and future students of the History Department of the University of Nottingham and most especially to the very splendid Jeannie Alderdice, Paul Bracken, Simon Constantine, Mike Evans, Paul Evans, Jon Porter, Kevin Sorrentino and Claire Taylor for their friendship, support, and thirst that made it all worthwhile.

To Tweed and Ray (my fellow ghosts in the library) whove taught me whats important, usually with glass in hand, my thanks although by now I dont suppose it should be necessary, and love to my sisters, Kate Green and Caroline Hamilton.

Im indebted to all those who have shared the Black Prince with me, especially those whose lectures and seminars may have focused rather more on Edward of Woodstock than they should have and who have often made me reassess my opinions or forced me to look at aspects of his life and career in different ways. In particular thanks are due to my Hundred Years War special subject group at the University of Birmingham.

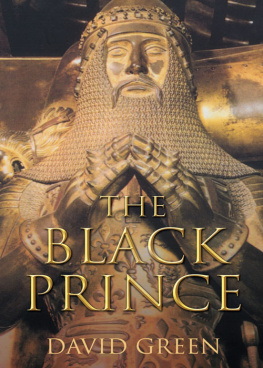

The need for a new biography of Edward, Prince of Wales and Aquitaine may not be self-evident. What more can or needs to be said about this figure whose reputation and character is so well known but has been so shaped and shrouded by chivalric myth; who has been seen as a brutal but no less shadowy representation of the worst and at the same time most praiseworthy characteristics of the late medieval period? In part, it may be enough to say that it is over 20 years since the last biography of the Black Prince was published, concluding a flurry of interest in Edward of Woodstock that was on a scale which had not been seen since the end of the previous century when his qualities were valued more highly. Much of the commentary in the intervening years has been negative. The impression, although not one often given by his biographers, has tended to be of a violent, grasping, profligate and arrogant man. That the prince could be all these things is not in doubt, but there was much more to the man that won his spurs in the vanguard at Crcy aged 16, who married for love and not for politics at 31 years (an extraordinary age for the heir-apparent), and who formed a vibrant court, the envy of Europe, at Bordeaux. For a man who was so much a product of his own time, he has been judged to a great degree by the standards of a later age. The success of a late medieval prince was determined in no small way by military talent, his ability to secure adequate finances from his estates, the successful distribution of those revenues in the form of patronage and as a demonstration of power, and pride in his lineage and achievements. That such priorities might be seen to descend into violence, avarice, profligacy and arrogance, is to some extent merely a matter of vocabulary. The intention of this book is not to provide a postrevisionist picture of the Black Prince, but to place him in context, to place him in the milieu in which he was, until the last years, almost effortlessly comfortable.

Recent years have seen the publication of a considerable body of scholarship concerning the late medieval period in general, notably the Hundred Years War, and the fourteenth century in particular. The rekindling of interest in medieval military history in conjunction with extensive work on the chivalric ethic has refocused interest on Edward the Black Prince. A central concern of this book will be the campaigns and expeditions which he undertook in 1346, 13556, 135960 and 1367, and the contemporaneous developments in matters such as strategy, tactics and recruitment in essence the professionalisation of the English (or Anglo-Welsh/Anglo-Gascon) armies. The Black Prince did not fight in a strategic or tactical vacuum, his methods of recruitment, funding and equipping his soldiers were shaped by an environment outside the experiences of his father, his commanders and the structures of local and national government. Indeed, it was those structures and the experiences of many of those that comprised the force which was victorious at Crcy that provided the platform for future success and established the English and their heir-apparent among the finest soldiers in Europe.

Of additional and particular interest is the period of the principality of Aquitaine (136271), which has been greatly under-represented in English works on the war. This and the reopening of hostilities in 1369 is too important an event to cast aside as simply the consequence of the overbearing pride of the spoiled heir-apparent.

This book has developed partly as a consequence of my doctoral thesis on The Household and Military Retinue of Edward the Black Prince, and if what follows seems not always to be as much a biography of Edward himself but of those that surrounded him, then it can be attributed to that research and also to a deliberate attempt to highlight the collective and individual importance of that exceptional company.

Edward, prince of Wales and Aquitaine, duke of Cornwall, earl of Chester, founder knight of the Order of the Garter, hero of Crcy, victor at Poitiers, the Black Prince, died on 8 June 1376, Trinity Sunday, the feast day for which he had particular reverence. It was recorded that the news was received in England and across the Channel with great sadness and mourning and not only for the sake of form. His life and death exemplified many of the incongruities of the political milieu in which he lived and his career mirrored the triumphs and disasters of the nation that he represented. Much of his brief life was characterised by war, and as the term Hundred Years War, the conflict to which the prince dedicated himself, has been misapplied to a punctuated confrontation that lasted at least 116 years, with the Plantagenets a dark instrument of divine (or diabolical) judgement. According to Shakespeare, King Charles VI of France (13641422) counselled his knights to fear Henry V because

he is bred out of that bloody strain That haunted us in our familiar paths: Witness our too much memorable shame When Cressy battle fatally was struck, And all our princes captivd by the hand Of that black name, Edward, Black Prince of Wales; While that his mountain sire, on mountain standing, Up in the air, crownd with the golden sun, Saw his heroical seed, and smiled to see him, Mangle the work of nature and deface The patterns that by God and by French fathers Had twenty years been made.

Such comments, made over 200 years after the death of the prince, may be seen as a mark of the impact made by both Edward III and his eldest son on the collective memory and imagination of the country. Politically and in terms of national reputation although such a concept was probably alien to the prince the years 134667 were unquestionably triumphant, and by contrast with the collapse of English power in France and the fractures of the Wars of the Roses in the fifteenth century, there was undoubtedly an Edwardian Golden Age to which those in the sixteenth century could look back.

Next page