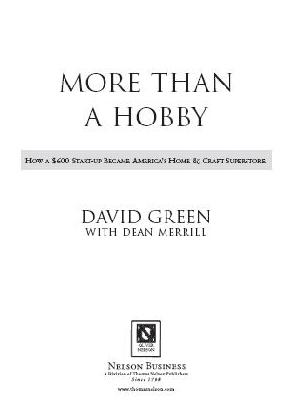

MORE THAN A

HOBBY

Copyright 2005 by David Green

All rights reserved. No portion of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any meanselectronic, mechanical, photocopy, recording, scanning, or otherexcept for brief quotations in critical reviews or articles, without the prior written permission of the publisher.

Published in Nashville, Tennessee, by Thomas Nelson, Inc.

Scripture quotations are from the HOLY BIBLE, NEW INTERNATIONAL VERSION. Copyright 1973, 1978, 1984 by International Bible Society. Used by permission of Zondervan Publishing House. All rights reserved.

Published in association with the literary agency of Mark Sweeney & Associates, 641 Old Hickory Blvd., Suite 416, Brentwood, Tennessee 37027.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Green, David, 1941 Nov. 13

More than a hobby : How a $600 Startup Became Americas Home-and-Craft Superstore / David Green with Dean Merrill.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references.

ISBN 0-7852-0831-3 (hardcover)

1. Retail tradeManagement. 2. Entrepreneurship. I. Merrill, Dean. II. Title.

HF5429.G6792 2005

658.8'7dc22

2005000098

Printed in the United States of America

05 06 07 08 09 QWK 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2

I dedicate this book to three ladies:

my mother, Marie, the inspiration of my life;

my wife, Barbara, the love of my life;

and my daughter and personal cheerleader,

Darsee, the light of my life.

I also dedicate it to my two sons, Mart and Steven,

whom I love dearly and hold in the utmost respect;

to my nine grandchildren, the joys of my life:

Brent, David T., Derek, Scott,

Lauren, Amy, Lindy, Danielle, and little Grace;

to my son-in-law, Stan,

whom God created especially for my daughter;

and to my two daughters-in-law, Diana and Jackie,

whom I call super-moms.

Because of their past and continued support and prayers,

my life has been fulfilled.

CONTENTS

You could smell the fresh popcorn as soon as you came through the front doors of McClellans five-and-dime on Hudson Street. The wooden floors creaked as you stepped toward the candy counter to the left or the toiletries department to the right, where a smiling young clerk would say, Good morning! as she waited to serve you.

If you passed by a little farther, you came to the second bank of counters. Sheets and towels were overseen by an older lady named Mrs. Duncan, while the toy department was enlivened by petite, energetic Ann, who was ready to kneel down and give any young boy or girl a squeeze. Nearby were the hosiery and lingerie sections, and on toward the back of the store came housewares, hardware, and pets. In charge of it all was a wiry, medium-height manager in his late fifties, Mr. T. Texas Tyler, who was always on the move.

McClellans sat on the east side of the courthouse square of Altus, Oklahoma, a county-seat town of some 20,000 in the middle of cotton fields and cattle ranches 220 miles northwest of Dallas. Not that our family came to shop very often at McClellans; we simply didnt have the money. My father was the pastor of a church with no more than thirty-five attendees, which meant a tiny salary despite the need to put food on the table for six kids. We had no car; we just walked wherever we needed to go. Aunts and cousins from California would occasionally send us hand-me-down clothes, which helped a great deal. That way our parents only had to fill in the socks and underwear.

The church people were as gracious as they could be, supplementing the meager collection funds with weekly poundingsa time in the service when they would bring vegetables, fruit, or other foodstuffs (sometimes by the poundhence, the name) to the altar to help the pastors family along. My mother accepted them all with warm appreciation. Still, we went weeks at a time without meat on our supper table. The idea of having an extra quarter or 50 cents we could spend at McClellans was far beyond our reality.

As a result, its little wonder that I didnt feel comfortable at Altus High School, in the swirl of students my age who had new clothes and money for snacks. I was the kid off to the side, the kid washing dishes in the cafeteria in order to earn a lunch pass. Its hard for me to remember any friends in high school. Id already had to repeat seventh grade, and whenever I was required to stand up and give an oral report in front of the class, I froze in my seat. I simply couldnt muster the courage.

David, the teacher would quietly say to me, Im sorry, but you must do this. If you refuse, I will have no choice but to give you an F.

Under those conditions, I would definitely take the F. I still hadnt recovered from the time a while back when I had mispronounced the word the, and everybody laughed. It was something about the oven or the Industrial Revolution, and I had said thuh instead of thee. My classmates thought that was hilarious.

So with a heavy sigh, my teacher would murmur, Okay, you come back at the end of school today and give your report just to me, with no one else in the room. That I was willing to do.

When I enrolled for my junior year in the fall of 1958, something absolutely wonderful happened. There on the class list was something called D.E.Distributive Education (more commonly called Work-Study today). What is that? I wanted to know.

Well, businesses in town call in to offer part-time jobs for students, a young teacher named J. W. Weatherford explained, and you get to leave during the school day to go work. You still get credit for the class, and you earn money along the way.

I was thrilled with this combination. I quickly signed up for the D.E. class. And thats how I entered the world of retail.

The first day that I left school at ten-thirty and walked the mile to McClellans, I was as excited as Id ever been. Welcome, son, Mr. Tyler greeted me. To get started, you go grab the yarn broom back there and sweep the floor. This was dusty Oklahoma, after all, and the aisles needed attention several times a day. He taught me to sweep with a compound of sawdust with some light oil mixed in.

When that was finished, Mr. Tyler said, All right, now lets go upstairs to the stock room. Ill show you how to check in the merchandise that just arrived. We went up to a room on the second floor where there were bins for each department and a long worktable for unpacking the cartons that the trucks delivered to our little 5,000-square-foot store. I saw the conveyor belt that chugged upstairs to the stockroom from the freight dock in the back. I saw the hand-crank machine that turned out price stickers so we could mark the merchandise before the ladies took it downstairs to display. Yes, price stickers; this was long before the days of bar coding, and few items were prepriced by the suppliers.

That evening, after I walked the mile back to our house across the tracks, I excitedly told my mother about my day. Now that I have a real job, I announced, Im going to buy you something really nice! I had worked alongside her and my brothers and sisters in the cotton fields for years to get money for our family. But this job at the five-and-dime was at a whole new level. Id much rather be doing this than sports or clubs after school.

Next page