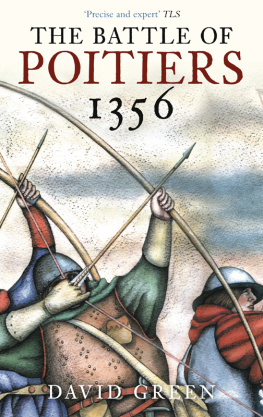

THE BATTLE OF

POITIERS

1356

THE BATTLE OF

POITIERS

1356

DAVID GREEN

Jacket illustrations: Courtesy of Kate Green.

This edition first published 2008

The History Press

The Mill, Brimscombe Port

Stroud, Gloucestershire, GL5 2QG

www.thehistorypress.co.uk

This ebook edition first published in 2013

All rights reserved

David Green, 2002, 2008, 2013

The right of David Green to be identified as the Author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyrights, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

This ebook is copyright material and must not be copied, reproduced, transferred, distributed, leased, licensed or publicly performed or used in any way except as specifically permitted in writing by the publishers, as allowed under the terms and conditions under which it was purchased or as strictly permitted by applicable copyright law. Any unauthorised distribution or use of this text may be a direct infringement of the authors and publishers rights, and those responsible may be liable in law accordingly.

EPUB ISBN 978 0 7524 9634 4

Original typesetting by The History Press

Contents

INTRODUCTION:

The Black Prince and

the Hundred Years War

Edward the Black Prince was born at Woodstock in 1330 some seven years before the formal outbreak of the Hundred Years War. The title now given to this conflict, one coined by modern historians, is something of a misnomer. Traditionally, the war is dated from 1337 to 1453 a period of 116 years but this does not take account of the broad nature of Anglo-French relations and hostilities in the medieval period. Conflict, although by no means constant, had been endemic long before 1337. In particular, tensions had grown since Henry III of England and Louis IX of France signed the Treaty of Paris in 1259, and these did not cease in 1453 with the fall of Bordeaux. Indeed, the English monarchy maintained its claim to the throne of France after the revolution of 1789 ensured that there was no throne for them to seize.

Like the conflict which he shaped and which dictated the course of his brief life and career he died in 1376 the name by which Edward of Woodstock is best known is the product of a much later age. There is no evidence for it being coined until the sixteenth century; the first example is found in Lelands Itinerary, and it was publicised by Raphael Holinshed, whose chronicles provided a source for Shakespeare in whose works the prince appears, as an example and model for Henry V and in his own right in Edward III, a play which has been accepted into the canon in recent years. The idea that the name derived from a penchant for black armour remains unsubstantiated as does the theory that the name was of French origin, brought on by his brutal raids and victories in battle. Nonetheless, the princes reputation in France was certainly black. It is, for example, apparent in the Apocalypse tapestries commissioned by Louis of Anjou in 1373 which depict Edward III and his sons as demons devastating the French countryside. Certainly, the English chevauche strategy, which the prince perfected in the 1355 raid burning his way across the belly of France from the Atlantic to the Mediterranean, meant that there was little love for this paragon of chivalry in France.

However, there is no doubt that he was considered among the most chivalrous of his generation. Late medieval chivalry was not an ethic or code of behaviour that restrained acts of violence; indeed it encouraged them. The image of the prince painted in the chronicles of Jean Froissart, and the verse biography written by the otherwise anonymous Herald of Sir John Chandos shows that prowess, skill-at-arms and military ability formed the foundations of chivalry. If the strategy that led to victory destroyed the reputation and revenue of ones enemy by burning and destroying the land, property and persons of non-combatants then this was, by definition, chivalrous. Unfortunately for the prince his success during the campaigns of 13556 contributed to later difficulties when he became prince and near-sovereign ruler of much of Aquitaine

The Black Prince is remembered above all as a warrior. Yet, his reputation as a military leader belies the small number of campaigns in which he was involved. He commanded the chevauches of 1355 and 1356 and the Spanish campaign of 1367, but in the Reims expedition (135960), as he had been at Crcy (1346), he served as his fathers lieutenant and had little responsibility for strategy. Nonetheless, he appears to have been an extremely capable leader of men and a daring tactician who also enjoyed an element of good fortune on the battlefield. But it is difficult to draw any firm conclusions about his military ability from these few examples. The Black Prince and the men under his command, particularly his chief captains and lieutenants, several of whom are described in further detail in the Appendix, played a vital role in a wider English strategy orchestrated by Edward III. The success of this strategy, encompassing both foreign and military policy broadly defined resulted in English (and Anglo-Welsh/Anglo-Gascon) armies building a European reputation. The triumphs of Crcy and Poitiers erased the disgrace of Bannockburn (1314), and gave the victors the status of the finest warriors in Europe. The associated military developments, which some have described as revolutionary, saw great advances in recruitment, provisioning, strategy and tactics. As the heir-apparent and his fathers lieutenant the prince exemplified these advances and took full advantage of them.

As a consequence, the Black Prince represents the broader English experience in the Hundred Years War. He fought in the vanguard at the battle of Crcy aged sixteen, and he witnessed the long siege of Calais (13467), which followed the triumph. Calais may seem a disappointing acquisition after such a comprehensive victory, certainly it may have been less than Edward hoped for, but the coastal town provided an excellent base for future military incursions and became a major trade centre when the wool staple was established there. The town saw further military action in 1350 which enhanced the princes reputation. The celebrated French knight Geoffrey de Charny offered Aimery of Pavia, governor of Calais, 20,000 crowns to betray the town in late October 1349. Aimery, however, passed on news of the plot to Edward III, and under the banner of Walter Mauny, the king and his eldest son, along with trusted knights such as Guy Brian successfully ambushed the attackers.

After the siege of Calais the devastation of the Black Death curtailed further large-scale military action. Intense diplomatic activity marked the years until 1355 when the prince and others led a number of devastating raids deep into the French countryside. In the following year the indignities heaped upon the French were compounded when the prince captured Jean II, the Good, king of France, at the battle of Poitiers. This marked the point at which the prince truly took his place on the European stage.

Pressing home their advantage the English launched a further expedition in 1359. This failed to capture the coronation city of Reims, and nor could the English take Paris, but in 1360 the French agreed to the treaty of Brtigny-Calais in 1360. The treaty offered a kings ransom for Jean II and the transfer of sovereignty over nearly a third of the kingdom of France to Edward III. Much of this was entrusted to his eldest son who in addition to his many estates in England and Wales received the title Prince of Aquitaine.

The treaty of 1360, although flawed, was a serious attempt to end the war, but it did not endure and set a dangerous precedent. Indeed, when Henry V embarked on the Agincourt campaign (1415) he did so demanding restitution of that which he claimed was still owed from the treaty of Brtigny. In this fashion the failures of diplomacy fanned the flames of the Hundred Years War. So too did many other lesser, regional conflicts that were dragged within the orbit of the Anglo-French war. These ensured the Hundred Years War became a truly European conflict.

Next page