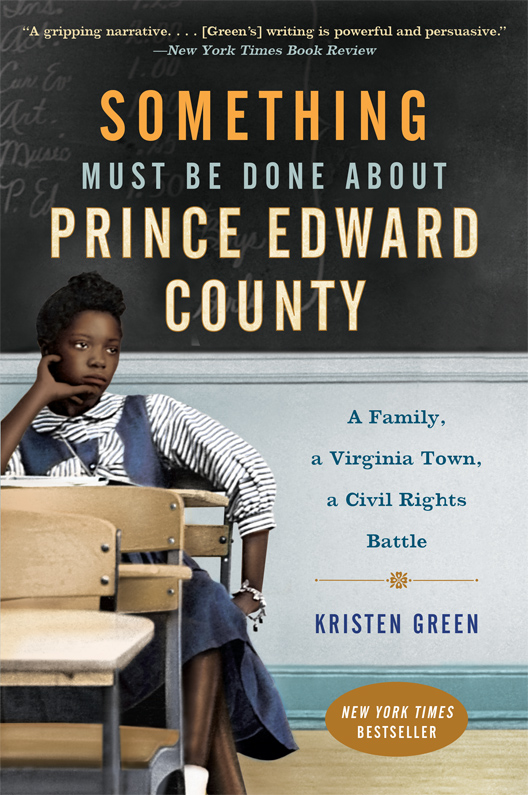

T his book is a hybrid of history and memoir. No names have been changed and no characters have been invented. In a limited number of instances, I have omitted an individuals name when it was not essential to the story. Anything in quotes was said to me, witnessed by me, or taken from a reputable publication. Sections of this book are written from my memory, which is, of course, fallible. I may remember events differently than other people.

I have chosen to refer to my familys longtime housekeeper, Elsie Lancaster, by her first name in this book because Elsie is what I have always called her. I refer to the students shut out of school by their first names because they are children when readers first meet them, and to avoid confusion, I chose to continue using their childhood names throughout. I use the term black instead of African American and white instead of Caucasian because this is how people refer to each other in my hometown to this day. I have included slurs, as offensive as they are, to accurately portray how people in Prince Edward spoke in the 1950s and 1960s, and how some people still talk today.

This book covers a period of more than sixty years. I have done my best to capture the key moments, both in Prince Edwards history and in Americas civil rights history, but I had to leave many paths unexplored for the sake of length and focus. In addition, I did not have space to include the stories of all of the students I interviewed who were shut out of school. On their own, they could have filled a book. Their experiences were heartbreaking, inspiring, and important. I wish I could have written about every last one of them.

I grew up thinking of her as our Elsie, not as someones mother. She was the black woman who had cleaned my parents house once a week since 1975. She had worked for my grandparents for two decades before that. Until I was in high school, she was also the only black person I knew.

Every Wednesday morning at nine, Elsie Lancaster appeared at the back door of our house in Farmville, a small rural town in southern Virginia. As a young child, I listened for Elsie to be dropped off and then ran to let her in. Petite and bird-thin, she wore a neat, pressed cotton blouse with a cardigan, an A-line polyester skirt, and pantyhose with sensible leather shoes.

Her shy face, typically cast down, brightened when she saw my three younger brothers and me. She hugged us, then quickly got to work, hanging her sweater in the closet by the front door and pulling out the Electrolux cylinder vacuum. She pushed it back and forth over the dark brown living room carpet while one of my twin brothers, a toddler at the time, rode on the back. She darted up the L-shaped staircase on wiry legs, her tiny but strong arms lugging the heavy cylinder behind her.

My mom would make a quick escape to run errands, leaving Elsie to keep an eye on my brothers and me. Elsie also swept and mopped the kitchen floor, scrubbed the bathroom sinks and toilets, and dusted the furniture. She hummed and sang while she worked, and Id trail behind her as she made her way through the house, waiting until she had silenced the vacuum for an opportunity to talk with her.

Mom returned in time to prepare sandwiches for lunch, and when I was older, I sat with Elsie and my mother around an oval oak table in our tidy kitchen. We held hands and prayed before the meal. God is great. God is good. Let us thank Him for our food. By His hands we all are fed. Give us, Lord, our daily bread.

My mom liked to say that Elsie was part of our family. My parents treated her better than other families who expected their housekeepers to eat separately. Mom bought Elsie birthday and Christmas presents, sent her home with vegetables from our garden, and, most important, treated her with kindness and respect. My grandmother prepared her lunch, instead of the other way around. Yet I didnt realize that Elsies own family had been ripped apart two decades earlier, when she was working for my grandparents, and that my grandfather was partly to blame.

In 1959, faced with a federal court order to desegregate the schools, Prince Edward Countys civic leaders refused to fund public education. They locked the doors of the public schools instead. It was a dramatic stance that set them apart from communities across the nation that preferred desegregated schools to closed schools. White leaders, including my grandparents, established a private school for their own children. The school was attended by both of my parents, and, years later, by my brothers and me as well. Black students like Elsies only childher daughter, Gwendolynhad nowhere to go. For five years, the public schools remained closed.

During my childhood, our family rarely discussed what had happened and only in broad strokes. No one mentioned that my grandfather had opposed integration. No one explained the effects of the school closures on our loyal housekeeper, her daughter, and other black residents of our county. And Elsie never revealed that she and her husband, Melvin, had made a heartbreaking decision to ensure that their daughter received an education. I didnt know that Elsie regularly replayed that decision in her mind, wondering if she had done the right thing. That she would second-guess it forever.

I didnt know that the past lived on, a painful history hidden in plain sight.

The only places on earth not to provide free public education are communist China, North Vietnam, Sarawak, Singapore, British Hondurasand Prince Edward County, Virginia.

US ATTORNEY GENERAL ROBERT F. KENNEDY, MARCH 19, 1963, LOUISVILLE, KENTUCKY

I t was a crisp autumn day when I stepped off the porch of my parents slate-blue house in Farmville and walked a block to the home of a man I had known most of my life, a man who founded the white private school I had attended. It had been fifteen years since Id graduated and left town.

I passed through the gate in front of his brick colonial, stepped onto his porch, and rang the doorbell. A black nurse answered the door. She escorted me through a formal living room, decorated with Oriental rugs and ornate lamps, to a dark den in the back of the house where Robert E. Taylor was sitting in a recliner, his feet elevated.

Taylor had always been a rotund man with a hearty laugh and a booming voice, a boisterous Southern storyteller who paused only long enough to take a puff of his pipe or to sip a cocktail. On this day, in November 2006, I found a different person. At eighty-seven, Taylor was a tamer, thinner version of himself, breathing with the help of oxygen.

I got pieces of both kidneys cut out and half a lung removed, he told me, and he was still hanging on.

For several years, I had wanted to learn more about what had happened in Farmville before I was born, events in which Taylor had played a key role. His daughter-in-law warned me that his health was failing and suggested that if I planned to interview him, I should do it soon. I wanted to talk about his lifes greatest work: the establishment of a whites-only academy, founded under the auspices of the Prince Edward School Foundation, which he oversaw for decades.

Taylor told me he supported the decision to close the public schools rather than integrate them. As a young businessman, he joined forces with other white town leaders, offering to use his contacts as a contractor to build a permanent location for the white school, Prince Edward Academy. Ive been on the board from the first day we talked about it, he said.