Contents

Guide

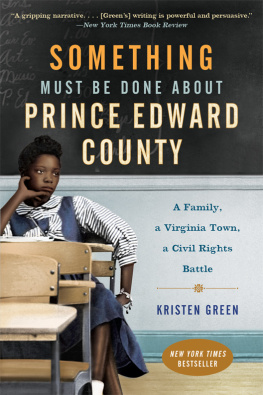

P. OConnell Pearson

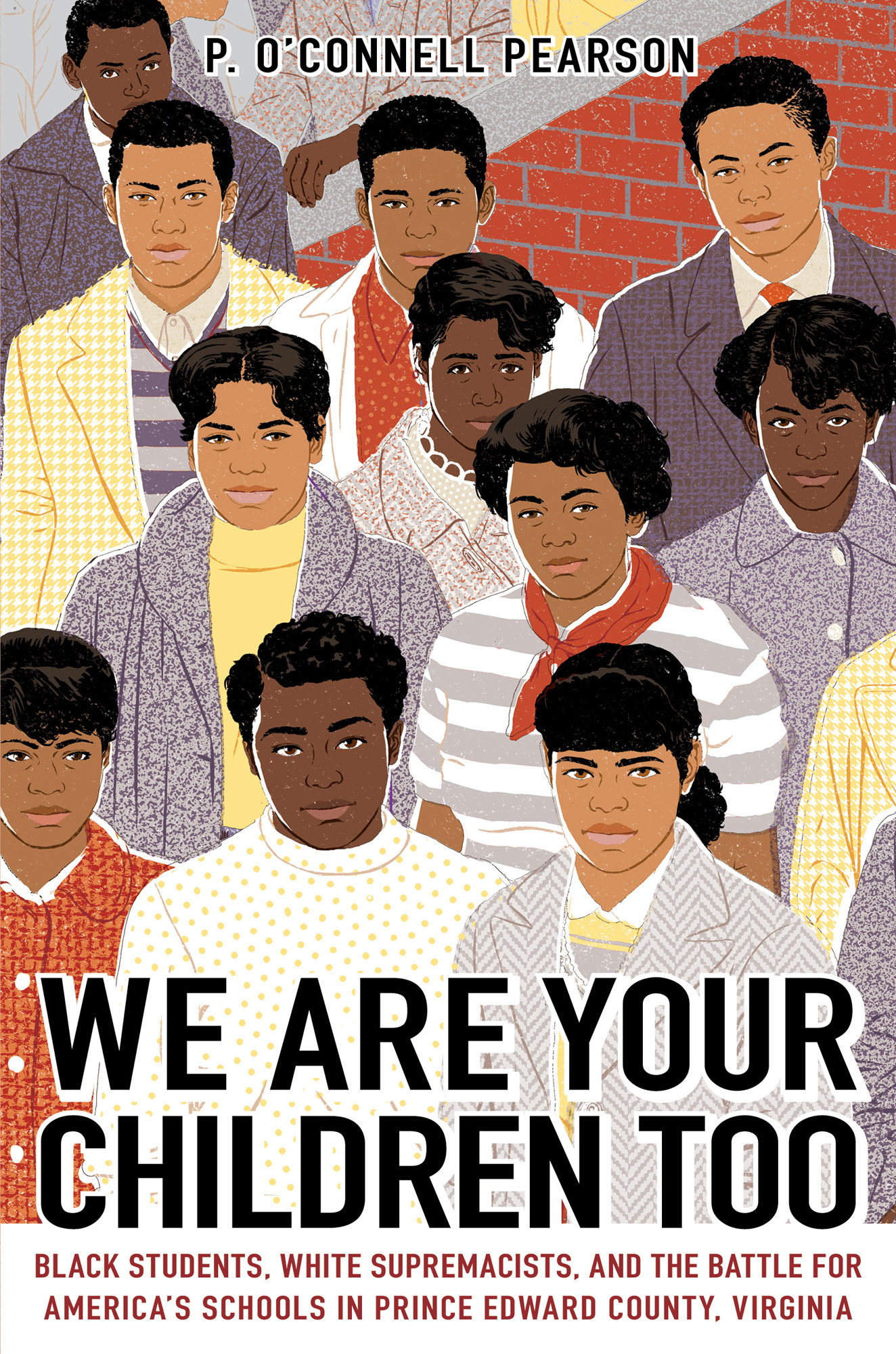

We Are Your Children Too

Black Students, White Supremacists, and the Battle for Americas Schools in Prince Edward County, Virginia

Also by P. OConnell Pearson

Fly Girls

Fighting for the Forest

Conspiracy

SIMON & SCHUSTER BOOKS FOR YOUNG READERS

An imprint of Simon & Schuster Childrens Publishing Division

1230 Avenue of the Americas, New York, New York 10020

www.SimonandSchuster.com

Text 2023 by Patricia OConnell Pearson

Jacket illustration 2023 by Cannaday Chapman

Jacket reference photograph by Hank Walker/The LIFE Picture Collection/Shutterstock

Jacket design by Sarah Creech 2023 by Simon & Schuster, Inc.

Interior photographs on courtesy of Christopher Spadone, copyright Christopher Spadone

All rights reserved, including the right of reproduction in whole or in part in any form.

SIMON & SCHUSTER BOOKS FOR YOUNG READERS and related marks are trademarks of Simon & Schuster, Inc.

For information about special discounts for bulk purchases, please contact Simon & Schuster Special Sales at 1-866-506-1949 or .

The Simon & Schuster Speakers Bureau can bring authors to your live event.

For more information or to book an event, contact the Simon & Schuster Speakers Bureau at 1-866-248-3049 or visit our website at www.simonspeakers.com.

Interior design by Hilary Zarycky

CIP data for this book is available from the Library of Congress.

ISBN 9781665901390

ISBN 9781665901413 (ebook)

For the many men and women of Prince Edward County, whose resilience and courage inspire

CHAPTER 1 UNEQUAL FALL 1950

B arbara Johns had been thinking. A lot. That didnt surprise anyone who knew herher grandmother described the sixteen-year-old as quiet, serious seemed she had to do a lot of thinking. Her mother said she was deep. But during the fall of 1950, Barbara was thinking about one thing in particular. One thing that had been bothering her for quite a while. When would something be done about her schoolRobert Russa Moton High School in rural Prince Edward County, Virginia?

All the students at Moton High agreed that their school was too small and badly equipped. Parts of it were a damp, drafty, dilapidated disaster. Barbara knew how the other students felt because they frequently talked about it at luncha lunch they had to bring from home since the school had no cafeteria. It had no gym, either. Or locker rooms, or science equipment. R. R. Moton High School (named for an educator from the area who had led the Tuskegee Institute in Alabama) had been built at the southern end of the town of Farmville in 1939 and had space for 180 students. It was sturdy enoughbrick with wood floors and tall windows. But by 1950, the student body numbered nearly five hundred, two and a half times the schools capacity. Under pressure from parents and the principal, the county school board had come up with a temporary solution: three rickety wooden outbuildings covered in a heavy paper coated with tarthe thick, black liquid used in roadbuilding. Often seen on chicken coops, the tar paper was supposed to keep rain out, but it didnt do its job very well at all. And it seemed that when members of the school board said temporary, they actually meant permanent.

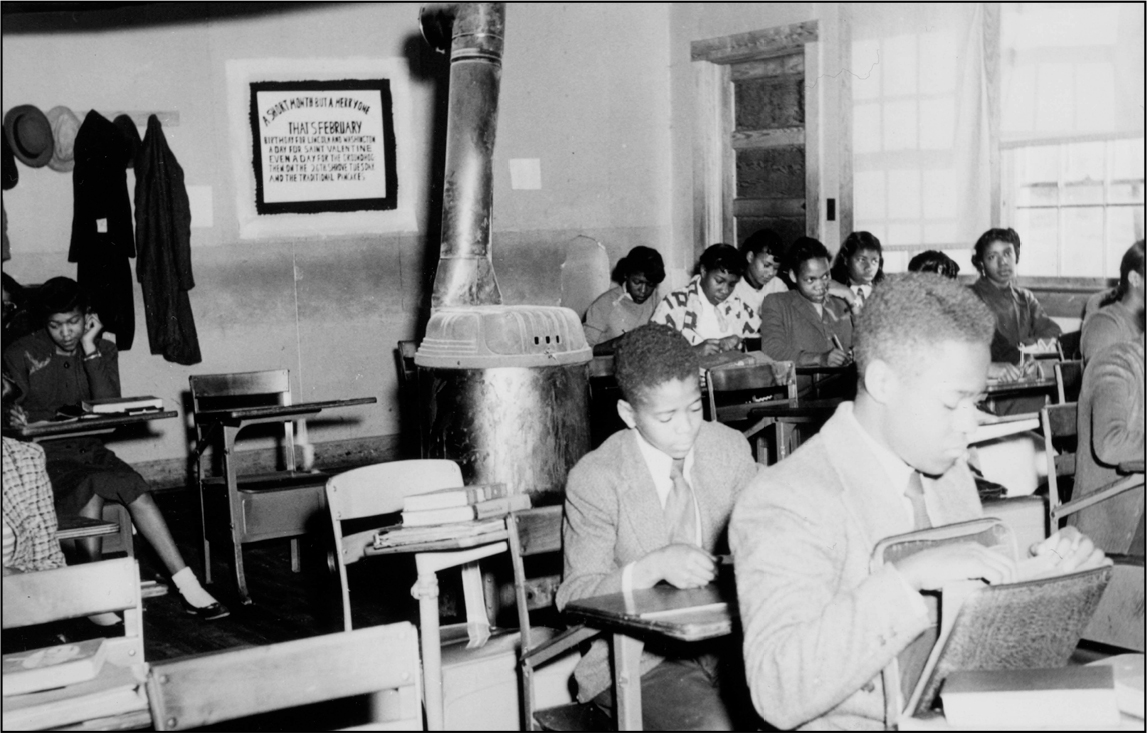

Students in an English class at R. R. Moton High School, c. 1951. The stove that heated the temporary classroom often sent cinders flying.

Not only did the tar paper shacksas everyone called themleak, but their only heat came from woodburning potbellied stoves at one end of each long, low structure. In winter, students sitting near the stoves felt ready to combust, while students in the back of the room wore their heavy coats during class. Hot coals sometimes jumped out of the stoves onto the wood floor, forcing whoever was nearby to scoop them back into the stove before the building caught fire. Students from other schools laughed and said the shacks looked like chicken coops. It was embarrassing. Worse, the shacks didnt come close to solving the overcrowding problem.

Several teachers had to meet their classes in the main buildings auditoriumreally just a big room with folding chairs and a small stagewhere the noise of many classes going on at once was terrible. Plus, the building was designed so that students moving from one wing of the school to the other had to walk through that auditorium, adding to the distractions. Some teachers taught classes in old, abandoned school buses parked beside the building. Others met their students outside unless it was raining.

Barbara and the other students complained about more than the actual buildings. There werent enough books to go around in most classes, and the books the school did have were old, out-of-date, and worn. Classroom equipmentdesks, chairs, blackboards, and the restwas old and worn too. And there were never enough basic supplies like paper or chalk.

Even getting to school was a challenge. Students came late or missed whole days because the secondhand school buses the county provided broke down frequently. Other children had to walk miles from the farms where they lived because the county didnt provide a school bus for them at all. John Stokes and his twin sister, Carrie, were eager to learn. Eager enough to walk four and a half miles along the gravel shoulder of a very busy highway to get to the overcrowded, poorly supplied Moton High School every day, no matter what the weather was like. Four and a half milesat least an hour and a half of walking each wayto get to classes in leaky, temporary buildings. John Stokes commented that the cows he milked had nicer buildings than the students at Moton did.

Imagine the determination it took for a young person to face that kind of discomfort, difficulty, even danger, every day just to go to school. For some students who didnt plan to go to college or trade school, a high school diploma didnt seem worth the terrible effort. Many were tempted to drop out, and who could blame them? Barbara Johns, who wanted very much to go to college, never considered quitting. But the idea of two more years at Moton was depressing, especially when after-school activities took her to other counties and she saw what their schools were like.

Barbara was a good student and a generally cheerful, rather quiet, person. But as much as she liked and respected her teachers and the principal, and as much as she enjoyed learning, R. R. Moton High School was wearing her down. It was wearing everyone down.

At sixteen, Barbara looked younger than her age. She had wide-set, almond-shaped brown eyes; dark, shoulder- length hair; and a big smile that lit up her whole face. She was soft-spoken, but not afraid to say what she thought, and she was comfortable talking to adults, the school music teacher in particular. Miss Inez Davenport made Barbara feel like she could tell the teacher almost anything. One day, when the situation at Moton High School had really gotten to her, Barbara told Miss Davenport just how fed up she was. It wasnt fair, she said, that she and all the other students had to attend a school with such dreadful equipment and miserable facilities.