Prince of Wales Edward - The black prince: the king that never was

Here you can read online Prince of Wales Edward - The black prince: the king that never was full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. City: Great Britain, year: 2016, publisher: Head of Zeus, genre: Art. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

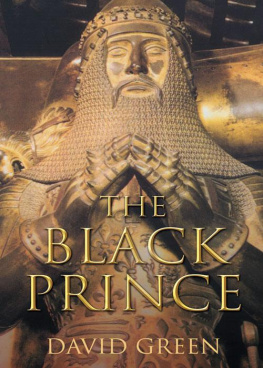

- Book:The black prince: the king that never was

- Author:

- Publisher:Head of Zeus

- Genre:

- Year:2016

- City:Great Britain

- Rating:5 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The black prince: the king that never was: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "The black prince: the king that never was" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

The black prince: the king that never was — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "The black prince: the king that never was" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

www.headofzeus.com

|

Let us do our utmost this day, in the name of God and St George, and acquit ourselves as all good knights should *

At the age of just sixteen, in 1346, he won his spurs at Crcy, where the French nobility were annihilated by English longbowmen. Nine years later he conducted a raid that scorched the earth of Languedoc. At Poitiers, in 1356, his victory over a numerically superior opponent forced the captured French king John II to bow to the terms of a treaty that marked the zenith of Englands dominance in the Hundred Years War. As lord of Aquitaine he ruled a vast swathe of territory across the west and southwest of France, holding a magnificent court at Bordeaux that mesmerized the brave but unruly Gascon nobility and drew them like moths to the flame of his cause.

He was Edward of Woodstock, eldest son of Edward III, and better known to posterity as the Black Prince. His military achievements captured the imagination of Europe: the chronicler Jean Froissart called him the flower of all chivalry; and for the man known as the Chandos Herald, who fought with him, he was the embodiment of all valour.

But what was the true nature of the man behind the chivalric myth, and of the violent but pious world in which he lived? Drawing on contemporary chronicles and a wide range of documentary material, Michael Jones tells the remarkable and inspiring story of one of the great warrior-princes of the Middle Ages and paints an unforgettably vivid portrait of warfare and chivalry in the fourteenth century.

* Words of the Black Prince to his soldiers before the Battle of Poitiers, 1356.

Nomenclature

Following usual convention, I have anglicized the names of the kings of France and members of the House of Valois, and also the dukes of Brittany and Burgundy. Medieval noblemen are usually referred to by their aristocratic title. However, when that title frequently changes, I have followed the convention of using their place of birth, for example in the case of Henry of Grosmont, who was successively earl of Derby, then earl and duke of Lancaster; and for John of Gaunt, who succeeded to the duchy of Lancaster after Grosmonts death. For clarity I have anglicized the Christian name of Peter IV of Aragon, but not his contemporary Pedro of Castile. To avoid confusion between the subject of this book, Edward of Woodstock, and his father, Edward III, I have for the former frequently used the appellation the Black Prince or the Prince (capitalizing to distinguish him from his younger brothers), even though it is a later term.

Measurements

Heights and dimensions are given using the metric system, with the imperial equivalent in brackets, and distances using the imperial system, with the metric equivalent in brackets.

Currency

In the fourteenth century England used a silver standard of currency. The unit of account was the pound sterling () which was equal to one and a half marks of silver. The pound was divided into twenty shillings (s), each of twelve pence (d). There was also, from 1344, a gold coinage based on the noble, which was conventionally worth 6s 8d, but was rarely used. It would, however, be significant in the calculation of the ransom of King John II and also in the introduction of gold coinage into Gascony and then the principality of Aquitaine by the Black Prince.

France also used a silver standard. The units of account were the livre tournois, the pound of Tours, and the livre bordelaise, the pound of Bordeaux, which was used in the duchy of Gascony, and would also be the currency for the principality of Aquitaine. These were also divided into twenty shillings ( sous) and twelve pence ( deniers). The pound sterling was worth five livres tournois and five livres bordelaises. The French gold coin, the cu dor (so named because the king was shown on the obverse side holding a heraldic shield (cu) but also referred to as a crown, was minted between 1337 and 1355. It was initially worth about 4s sterling, but by the time of the Black Princes raid in 1355 the quality had been reduced and its value had fallen to slightly less than 3s. In the ransom negotiations with John II the rate of the cu was fixed at half a noble, that is 3s 4d. One of the many achievements of Charles V would be to mint a coinage that kept a stable value.

The gold florin of Florence circulated in both countries and was the nearest thing to an international standard of value in fourteenth-century Europe. It was worth slightly less than 3s. The Black Princes campaign in Spain in 1367 also gave rise to a number of transactions in the Castilian gold coin the dobla, which was struck in quantity from the reign of Alfonso XI and was worth a little less than 4s.

On his arrival in Bordeaux in September 1355 the Black Prince introduced a gold coin, the lopard, into Gascon currency (on 29 September), as an equivalent to the English noble (6s 8d), although its real value in the late 1350s was actually a little over six shillings sterling. On the creation of the principality of Aquitaine in July 1362 he was granted the right to strike gold and silver coin in his own name and image. The two most interesting gold coins are the pavillon dor (struck in 1364, and described in the text, in Chapter Seven), and the hardi dor, struck in the summer of 1368. Again, both were equivalents of the English noble.

The hardi dor was the result of negotiations with the estates of Aquitaine at Angoulme in January 1368 where, in return for the right to levy the fouage , the Prince promised to keep currency values stable (the gold content of the pavillon had dropped, reducing its value to around 5s 6d sterling). Its design suggests an intimation of the troubles ahead. It features a prominent display of the Princes sword, held aloft with the militant reverse legend My strength comes from the Lord, as if already anticipating a French attack. But within months of it being minted, the Black Prince was confined to his bed with illness.

Sources

The unfolding narrative of the Black Princes life draws on a wide variety of sources, primary and secondary, which are listed in the Bibliography and referred to in the Notes. Some brief comments should be made about one particular source, the life of the Prince composed (around 1385) by the Chandos Herald. We do not know this Heralds name, but he probably came from Hainault and he and the chronicler Jean Froissart seem to have known each other (Froissart uses his work, particularly for the Princes expedition to Spain in 1367). The Herald was in the Black Princes service in Aquitaine in the 1360s and it is his account of the Njera campaign, of which he was an eye-witness, that is of particular interest.

Extracts from the Chandos Herald are rendered in prose, although in its original form it was a French poem of some 4,000 words. Its modern title of convenience, The Life of the Black Prince, would have probably bewildered its medieval author, whose intention was to describe the feats of arms, the chivalric credentials, of his hero the most noble Prince of Wales and Aquitaine. The poem exists in two manuscripts: one held at Worcester College, Oxford, the other at Senate House Library, University of London (Mildred Pope and Eleanor Lodge made a reliable prose translation from the former in 1910; Diana Tyson compared both texts in 1975). It is laudatory and uncritical and like all primary source material needs to be used with care. And yet the sense of drama that unfolds within its pages, as the Princes army crosses the Pyrenees by the pass of Roncesvalles in atrocious winter weather, and camps out before the battle of Njera (fought on a fair and beautiful plain, where there was neither bush nor tree) in an orchard, under the olive trees, reminds us that at heart the Black Princes life is a powerful human story and one of both triumph and tragedy.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «The black prince: the king that never was»

Look at similar books to The black prince: the king that never was. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book The black prince: the king that never was and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.