CONTENTS

FOREWORD

BY WENDELL BERRY

AFTERWORD

BY WILL ALLEN AND ERIC SCHLOSSER

THE EXTREME DESTRUCTIVENESSAND THEREFORE THE FRAGILITYOF INDUSTRIAL AGRICULTURE IS NOT A SECRET.

FOREWORD

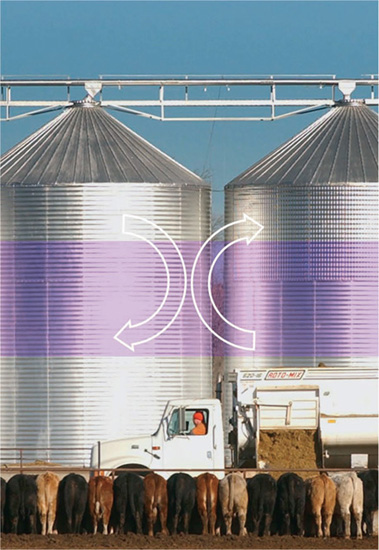

THE INDUSTRIAL MIND, as it is manifested in agriculture, solves problems one at a time by single solutions usually large in scale and always highly profitable to some branch of agribusiness. Thus to produce the greatest possible quantity of corn in the American Midwest, the approved means is chemical nitrogen in massive doses. This does enable gigantic corn harvests, weather permitting and temporarily, which fulfills the single purpose of nitrogen fertilizer. But to secure this one result it is necessary to ignore vital questions having to do with the health of the soil, of local ecosystems and their watersheds, of the watershed of the Mississippi River, and of the waters of the Gulf of Mexico. Those questions lead in turn to questions about the physical and economic health of human beings. And all those questions lead ultimately, and frighteningly, to questions about the long-term availability of natural gas, from which we make nitrogen fertilizer, with which we grow our present vast acreages of corn.

Vast acreages planted continuously in corn or soybeans produce a lot of corn and soybeans. So many acres, so many bushels per acre, were urgently required, we were told by the publicists and politicians, to feed the world. Now to that urgent requirement another, equally urgent, has been added: the production of biofuel to hasten the day of energy independence. And so the vast acreages devoted to annual row crops must become yet more vast. As a consequence, all of these millions of acres are annually exposed to erosion and degradation of the soil, and the chemical runoff plays the devil with water quality. Again, we confront the question of long-term sustainability. And the answer is inarguable: This way of food production is destructive of everything it depends on. It cant last.

The extreme destructivenessand therefore the fragilityof industrial agriculture is not a secret. It is obvious to anybody who will look and learn. Knowledgeable people have been speaking of it and writing about it since the first half of the last century. But those knowledgeable people have been mere citizens. Arrayed against them have been, of course, all agricultural industrialists and all agribusiness corporations, but also all the stars of academic and scientific agriculture and every politician of any significance. It may be understandable that many influential politicians discredit the warnings about climate change, for climate change, maybe, is not obvious. But when practically every economist, scientist, intellectual, and politician ignores or denies agricultural damages that are measurable, massive, and obvious, then we are living just as obviously in an age of official insanity.

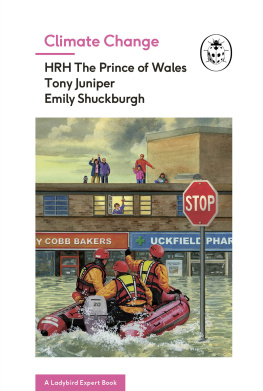

So far as I know, only one eminent person has had both the clarity to see and the courage to speak candidly about the obvious failures and dangers of industrial agriculture. That person is Prince Charles of the United Kingdom, who took his stand and made his challenge to industrial agriculture many years ago. Americans may be inclined to think that he has been free to do this because his position is not elective. But like no American politician, he belongs for life to his constituency, many of whom no doubt expect him to support their conventional assumptions about agriculture. When he speaks of challenging those assumptions as extremely dangerous and a risky business, one may confidently assume that he knows what he is talking about.

In Washington, DC, on May 4, 2011, Prince Charles delivered a speech the text of which is provided in this little book, and which was, by any measure, remarkable. It was most certainly a challenge to conventional assumptions, but it was nothing like the speeches on public issues that we are getting accustomed to in the United States. It was not a volley of angry slogans and loose assertions. On the contrary, Prince Charless terms were clearly defined; his argument was made carefully and in detail; his speech was quietly voiced, and the more powerful for that. He did not speak as a blinkered partisan of a side, but rather, as a human to other humans, of concerns urgently important to us all.

He said that we humans are under obligation to increase the long-term fertility of the soil.

He said that we need a form of agriculture that does not exceed the carrying capacity of its local ecosystem and which recognizes that the soil is the planets most vital renewable resource.

He said that we need to do everything possible, and use the best new technology, to conserve water.

He said that social and economic stability is built upon valuing and supporting local communities and their traditions, and that smallholder agriculture therefore has a pivotal role.

He said, Capitalism depends upon capital, but our capital ultimately depends upon the health of Natures capital.

There is nothing extreme or odd in anything I have quoted, or in the speech as a whole, which amounts exactly to the good sense that we once recognized as common. That this sense is now so rarely spoken, and that a prominent man needs rare courage to speak it, tells us how highly we should value this speech, and how fortunate we are to share the world, in our difficult time, with this speaker.

WENDELL BERRY

ON MAY 4, 2011, HIS ROYAL HIGHNESS THE PRINCE OF WALES GAVE THE KEYNOTE SPEECH TO THE FUTURE OF FOOD CONFERENCE AT GEORGETOWN UNIVERSITY, WASHINGTON, DC. THIS ESSAY HAS BEEN ADAPTED FROM THOSE REMARKS.

SOILS ARE BEING DEPLETED, DEMAND FOR WATER IS GROWING EVER MORE VORACIOUS, AND THE ENTIRE SYSTEM IS AT THE MERCY OF AN INCREASINGLY FLUCTUATING PRICE OF OIL.

THE PRINCES SPEECH

THE WORLD is gradually waking up to the fact that creating sustainable food systems will become paramount in the future because of the enormous challenges now facing food production.

The Oxford English Dictionary defines sustainability as keeping something going continuously. And the need to keep things going for future generations is quite frankly the reason I have been venturing into extremely dangerous territory by speaking about the future of food over the past 30 years. I have all the scars to prove it ! Questioning the conventional worldview is a risky business. And the only reason I have done so is for the sake of the younger generation and for the integrity of Nature herself. It is your future that concerns me and that of your grandchildren, and theirs too. That is how far we should be looking ahead. I have no intention of being confronted by my grandchildren, demanding to know why on Earth we didnt do something about the many problems that existed when we knew what was going wrong. The threat of that question, the responsibility of it, is precisely why I have gone on challenging the assumptions of our day. And I would urge you to do the same, because we need to face up to asking whether how we produce our food is actually fit for purpose in the very challenging circumstances of the 21st century. We simply cannot ignore that question any longer.

Next page