Contents

About the Book

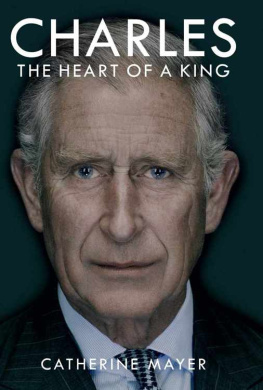

A startling portrait of Charles,Prince of Wales, that sheds light intopreviously unseen corners of his life.

He is one of the worlds most fascinating andleast understood figures, and emerges as acomplex character, driven by past pain andby a personal philosophy that links his viewson everything, from architecture and theenvironment to mutton. He is set to reshapethe monarchy in his own image.

Based on exclusive interviews with membersof the Princes inner circle and underpinnedby rare direct access to the Prince himself, thisrevelatory biography takes us deep into hisworld, illuminating his struggles and passions,his achievements as a philanthropist and theskulduggery of court life. It also offers afundamental reappraisal of one of the mostdocumented episodes of modern history, hisfirst marriage.

The reality, as in many aspects of the Princesstory, is more gripping and more poignant thanwe imagined. This biography explains whyCharles will never be remote and silent like hismother, and it lays bare the astonishing extentto which the princely activist has already lefthis mark on the world.

About the Author

Catherine Mayer is Editor at Largeat TIME magazine. She has been coveringEuropean and international current affairsfor three decades and has profiled theleading figures in many fields, includingPresidents and Prime Ministers, culturaland business leaders, and royals.

To Andy, perennially

Authors Note

In October 2013, a short teaser on TIMEs website generated headlines across the world. These headlines quickly described a narrative arc of their own, from the factual PRINCE CHARLES IN NO HURRY TO BECOME KING

Teased or not, the cover story was always bound to draw attention, and not just because Charles emerged as a bit of a charmer, who inspired his close friend, the actor Emma Thompson, to the tongue-in-cheek observation that dancing with him was better than sex. (The quote in my TIME profile, which launched a first set of lurid headlines, had in fact been truncated for space. Who knows what the tabloids would have made of Thompsons unexpurgated tribute: Hes a great, great dancer. Hes the best dancer. Not disco-dancing. Proper dancing. Ive never danced with anyone who can actually lead me and I can just relax and go, this is great, this is better than sex. Hes a very charismatic, virile dancer.)

I had been given remarkable access by the standards of royal press management, which is to say, nowhere near as much as a TIME journalist might expect from a President or Prime Minister, but enough to get a strong sense of my quarry and for him to get a sense of me. Before the project could be green-lit, he met me and spoke to me off the record. For six months, I trailed him, came close to learning to remember to curtsey every time we met, listened to his speeches and his jokes visited his homes, struggled to keep up with him as he strode across muddy fields, attended a private concert at his Welsh bolthole, mingled at multiple events to promote his charities and initiatives, on one occasion in 2013 I dined with him at the Scottish mansion Dumfries House, listened in on one of his private meetings (and inevitably became drawn into the discussion that took place), interviewed a substantial number of people close to him, negotiated a photo shoot of the Prince by photographer Nadav Kander (the cover of this book features one of Kanders extraordinary portraits) and eventually sat down in his living room in Birkhall to an on-the-record conversation with him.

His aides at Clarence House the name of his London home and the collective name for his staff agreed to the Prince speaking on condition that this would not be billed as an interview and that he could review his quotes pre-publication. A few of the most revealing things he said ended up on the cutting-room floor; so did some utterly innocuous remarks. Monarchy moves in mysterious ways. I did not use any rewritten quotes that changed the meaning of the original. About half of the interviewees, particularly those working for the royal households or Charless charities and initiatives, insisted that I send their comments about HRH or the Boss for prior approval, and like the Prince excised the anodyne as well as the controversial. Other sources opted to remain anonymous.

Similar preconditions were necessary to secure some of the many additional interviews conducted for this book. These did not include a second recorded conversation with Charles. In January 2014, I travelled back to Dumfries House to research a second piece and accompanied Charles on a long march around the estate, lasting about five hours. I seized many additional opportunities to observe him at close quarters, for example in May of the same year accompanying him and the Duchess of Cornwall on their official visit to Canada, interacting with both of them and watching them interact with others.

There is a convention that private conversations with royals are not to be quoted directly. The definition of a private conversation is less than crystalline. One such conversation, between the Prince and a volunteer guide at the Canadian Museum of Immigration at Pier 21 in Nova Scotia, found its way into the Daily Mail, prompting a diplomatic spat with Russia. The Mail explained its decision to publish on the basis that the volunteer had been standing in the official line-up at the museum. I decided in this book to quote from a few conversations that Clarence House would class as private for example, between Charles and a collective of Welsh butchers to give a flavour of the way he speaks and how he engages with people, but I have steered clear of repeating any remarks that would lend themselves to headlines either because they misrepresented his true views or revealed them all too clearly but without context.

In other circumstances, a biographer could rely on previously published work to fill in the gaps. With Charles, for reasons set out in greater detail in the pages that follow, that would be problematic. Many secondary printed sources are unreliable. So my voluminous reading has been supplemented by multiple interviews with people who know Charles well. One person close to him sent me a heartening email after we spoke, saying that I had clearly come to understand the essence of the Prince. I hope so. I have also drawn on a large body of research about the royals amassed over three decades, most recently as the author of four TIME cover stories and co-author of a TIME book and also as the editor and behind-the-scenes point person for a TIME cover story on the Queen in 2006 for which I also interviewed Prince Andrew. Two years before that I had shadowed Andrew on one of his trade missions to China and interviewed him in Beijing. Ive been delving into the royals since the Diana years. Every encounter with Prince Charles, his family, staff and friends, quotable or not, has deepened my understanding. Controlled access is better than the only alternative open to the vast majority of biographers: no access.

The Queen has never given an interview, by that name or any other; her children and grandchildren rarely do so. The Freedom of Information Act exempts communications with the Queen, Prince Charles and the second in line to the throne, William, from public scrutiny (though at the time of going to press the Supreme Court is mulling a challenge to the strictures against revealing the content of some of Charless correspondence). Palace staff sign confidentiality agreements. Royal press secretaries almost never comment on stories deemed to stray into the ever-narrowing sphere of the purely personal. That policy means some journalists inevitably make honest mistakes based on faulty information from trusted sources cultivated to supplement the meagre fare provided by close-lipped royal aides. More unscrupulous reporters see in such reticence a licence to fabricate or embroider stories which they calculate the palace will find too trivial or intrusive to rebut. Theres an assumption, too, that the royals will not sue. So the world is awash with royal nonsense. Inaccuracies and inventions, left unchallenged, are repeated. Repetition gives credence. Once a sufficient number of news organisations has repeated a fiction, it becomes a multi-sourced fact. News-gathering in the age of aggregation is a giant game of Chinese whispers, in which stories become, like the Princes eggs, more scrambled with each retelling.

Next page