Mark Kishlansky

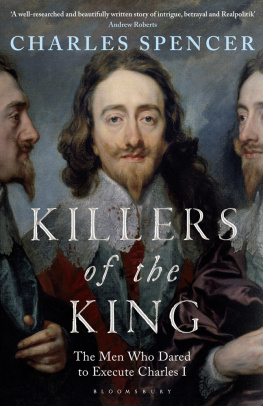

CHARLES I

An Abbreviated Life

Contents

Penguin Monarchs

THE HOUSES OF WESSEX AND DENMARK

| Athelstan | Tom Holland |

| Aethelred the Unready | Richard Abels |

| Cnut | Ryan Lavelle |

| Edward the Confessor | James Campbell |

THE HOUSES OF NORMANDY, BLOIS AND ANJOU

| William I | Marc Morris |

| William II | John Gillingham |

| Henry I | Edmund King |

| Stephen | Carl Watkins |

| Henry II | Richard Barber |

| Richard I | Thomas Asbridge |

| John | Nicholas Vincent |

THE HOUSE OF PLANTAGENET

| Henry III | Stephen Church |

| Edward I | Andy King |

| Edward II | Christopher Given-Wilson |

| Edward III | Jonathan Sumption |

| Richard II | Laura Ashe |

THE HOUSES OF LANCASTER AND YORK

| Henry IV | Catherine Nall |

| Henry V | Anne Curry |

| Henry VI | James Ross |

| Edward IV | A. J. Pollard |

| Edward V | Thomas Penn |

| Richard III | Rosemary Horrox |

THE HOUSE OF TUDOR

| Henry VII | Sean Cunningham |

| Henry VIII | John Guy |

| Edward VI | Stephen Alford |

| Mary I | John Edwards |

| Elizabeth I | Helen Castor |

THE HOUSE OF STUART

| James I | Thomas Cogswell |

| Charles I | Mark Kishlansky |

| [Cromwell | David Horspool] |

| Charles II | Clare Jackson |

| James II | David Womersley |

| William III & Mary II | Jonathan Keates |

| Anne | Richard Hewlings |

THE HOUSE OF HANOVER

| George I | Tim Blanning |

| George II | Norman Davies |

| George III | Amanda Foreman |

| George IV | Stella Tillyard |

| William IV | Roger Knight |

| Victoria | Jane Ridley |

THE HOUSES OF SAXE-COBURG & GOTHA AND WINDSOR

| Edward VII | Richard Davenport-Hines |

| George V | David Cannadine |

| Edward VIII | Piers Brendon |

| George VI | Philip Ziegler |

| Elizabeth II | Douglas Hurd |

For the three Ms

Preface

I have lived with Charles I for more years than I care to remember. With such intimacy comes ambivalence. He was a man and a monarch who has never been given his due even if his reign was a disaster for his three kingdoms. Highlighting his virtues downplays his faults, while emphasizing his vices downplays his achievements. Removing some blame from Charless shoulders and placing it on those of his opponents rebalances our understanding of the mid-seventeenth-century crisis. Such an undertaking is not likely to make Charles or this author more popular. But a shift of perspective opens wide new vistas of historical understanding. It is hoped that seeing the king from his point of view will force a re-evaluation of historical interpretations that have remained unchanged for centuries.

It was Montaigne who first said, I wrote you a long letter because I didnt have time to write a short one. Writing an abbreviated biography was an equally terrifying challenge. It enforced not only an economy of style, but an economy of perspective. Relating only what the reader needed to know in order to follow the story meant ignoring much of significance and making hard choices. In all cases I have opted for narrative flow rather than interpretive complexity. My aim has been to make Charles an easy read despite his being a complex man.

During the time frame of this study, England used the Julian calendar in which the year was reckoned to begin on 25 March. In this book, all dates are given New Style with the year beginning on 1 January. In an aristocratic society, men acquired titles and elevations of rank during their lifetime. I have taken the liberty of designating them by the title by which they are known historically even if they hadnt yet received it by strict chronology. Finally, matters of money present challenges both historical and contemporaneous. Most statements of royal revenue and debt are approximations and are best used as comparisons rather than absolutes. For the curious, there are a number of calculators of the historical worth of money. In spending value, 100 in 1625 is equivalent to 16,000 in todays money. Finally, spelling and punctuation have been modernized in quotations from primary sources.

Mark Kishlansky

Cambridge, Mass.

Prologue

Even his virtues were misinterpreted and scandalously reviled. His gentleness was miscalled defect of wisdom; his firmness, obstinacy; his regular devotion, popery; his decent worship, superstition; his opposing of schism, hatred of the power of godliness.

Charles I is the most despised monarch in Britains historical memory. Considering that among his predecessors were murderers, rapists, psychotics and the mentally challenged, this is no small distinction. In most modern accounts, he is portrayed as a mean, petty and vindictive tyrant who brought misery to his subjects and ruin to his nation. However, Charles did not earn these censures by having an aberrant personality; indeed his characteristics were mostly laudable. He had refined sensibilities and loved art, music and dance as a connoisseur rather than as a dilettante. He was a religious man, at prayers daily, attentive to sermons, and he died a martyr to his Church. Abstemious, he dined moderately and diluted his wine to keep a clear head. His court was in decorous contrast to the boisterous one he inherited. He himself was never obscene in his speech, or affected it in others.neither mistresses nor lovers, and a doting father before his children were ripped from him by the disaster of civil war. He even aspired to make England a great European power. All of this should have weighed in his favour.

Charles lived in an age that attributed historical catastrophes to the will and personality of individuals. In a monarchy, the king was the obvious prime mover. But many contemporaries found only modest faults in his character. The Earl of Clarendon, who knew the king better than most, believed that he was too soft, unwilling to slip the iron fist inside the velvet glove. The Archbishop of Canterburys chaplain, Peter Heylyn, who also observed the king first hand, remembered a maxim of King Charles that it was better to be deceived, than to distrust. This piety, Heylyn regretted, proved a plain and easy way unto those calamities which afterwards were brought upon him. If these were grievous faults, then grievously did he pay for them.

The process of demonization began in the 1640s among Parliamentarians who blackened the reputation of the king. They spoke of tyranny and claimed that the monarch had pursued a malignant and pernicious design of subverting the fundamental laws and principles of government.minister, they spun a fantasy of a king so bent on destroying his own people that he planned to turn an Irish army loose in England. Thus when it became necessary to raise an army to suppress the Irish Rebellion, it was impossible for Parliament to trust the king to lead it. While overt criticism of Charles in Parliament was still largely muted in the early 1640s, the unlicensed press proved less circumspect. The king was satirized, caricatured and traduced. All of this made it possible to take up arms against him and ultimately to bring him to his death.