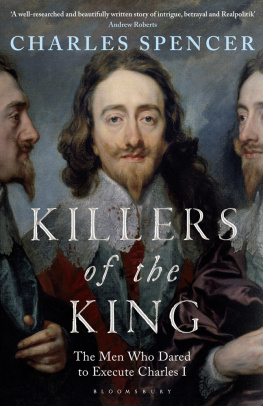

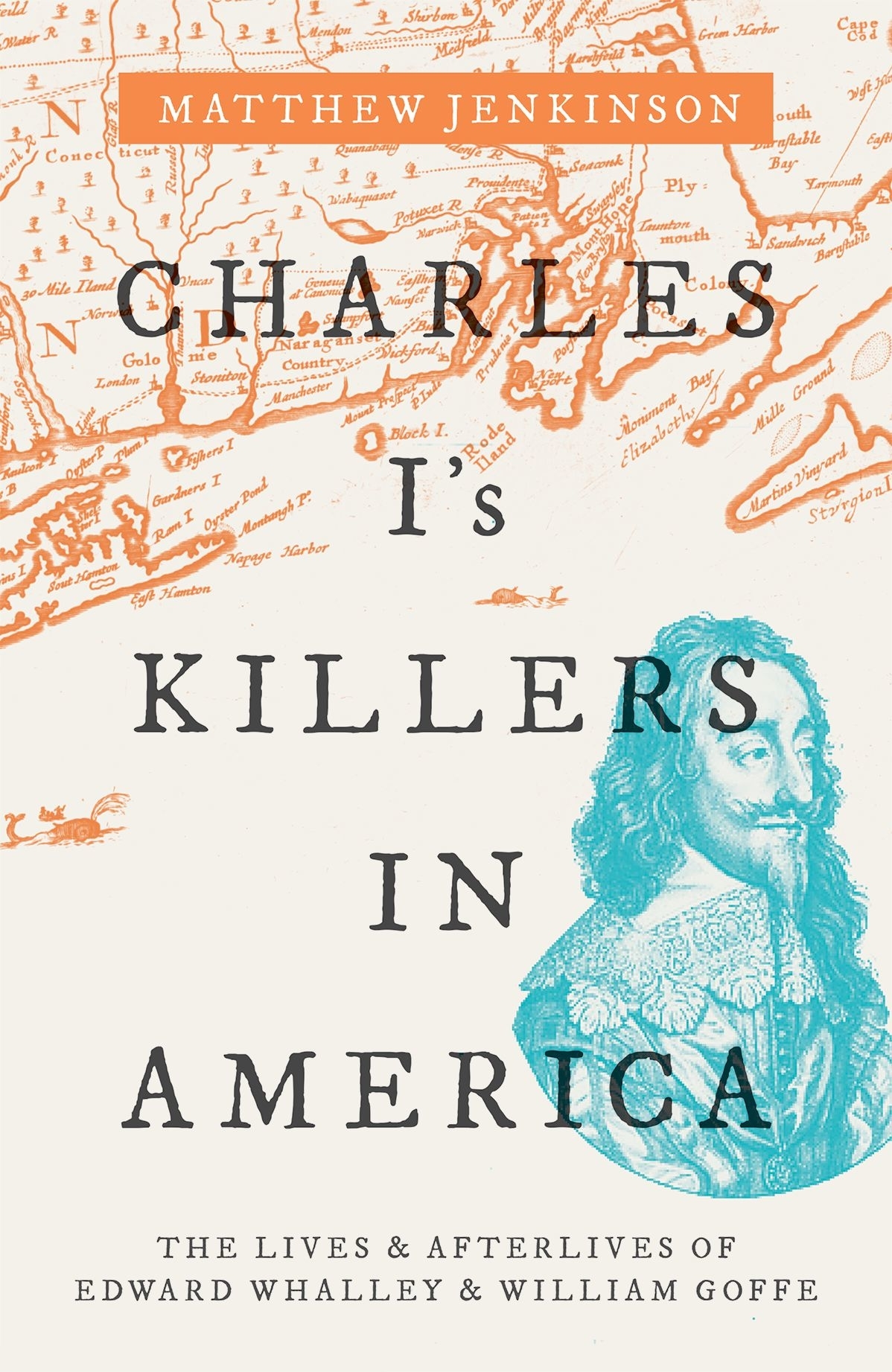

CHARLES Is KILLERS IN AMERICA

Great Clarendon Street, Oxford, ox 2 6 dp , United Kingdom

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the Universitys objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide. Oxford is a registered trade mark of Oxford University Press in the UK and in certain other countries

Matthew Jenkinson 2019

The moral rights of the author have been asserted

First Edition published in 2019

Impression: 1

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of Oxford University Press, or as expressly permitted by law, by licence or under terms agreed with the appropriate reprographics rights organization. Enquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope of the above should be sent to the Rights Department, Oxford University Press, at the address above

You must not circulate this work in any other form and you must impose this same condition on any acquirer

Published in the United States of America by Oxford University Press

198 Madison Avenue, New York, NY 10016, United States of America

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

Data available

Library of Congress Control Number: 2018956450

ISBN 9780198820734

ebook ISBN 9780192552570

Printed and bound in Great Britain by Clays Ltd, Elcograf S.p.A.

Links to third party websites are provided by Oxford in good faith and for information only. Oxford disclaims any responsibility for the materials contained in any third party website referenced in this work.

In memory of

B.E. Bevill

H.F.B. Bevill

E.J. Jenkinson

L.E.S. Jenkinson

Preface

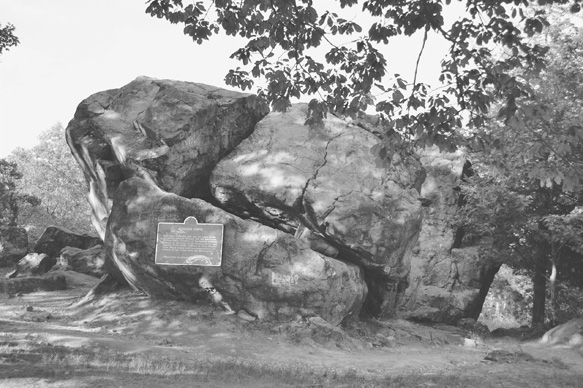

If you drive about three miles north-west of Yale University, up the winding roads of New Havens West Rock Park, you come to a collection of large boulders. These rocks or erratics were deposited between ten and twenty thousand years ago, when a layer of glacial ice melted at the end of the last ice age, leaving a small network of narrow passages that are just large enough to conceal two adults from public view. A small plaque on one of the rocks notes that this hiding place was used, in the 1660s, by two men who had been complicit in the trial and execution of Charles I, the only king in British history to be tried and then put to death. Indeed, these men had signed the kings death warrant. On the run from agents sent to bring these regicides to justice, Edward Whalley and William Goffe concealed themselves in what is now called the Judges Cave (the apostrophe has been removed). If we go forward three hundred and fifty years, the cave is still there and is still being used for the purposes of concealment; though, in the early twenty-first century, this is the concealment of young couples anxious to keep their liaisons away from disapproving eyes. The rocks themselves are covered in graffiti (see ), some of which reflects the affection between various couples. The only inscription that appears to have any connection whatsoever to the devout Puritan regicides declares Dear God, thank you for this cave. It is unclear whether the graffitis author is thankful for its concealment of Whalley and Goffe, for its geological interest, or for the opportunity to pursue a relationship away from parental scrutiny.

Figure 1. Photograph of the Judges Cave, New Haven, featuring twenty-first-century graffiti

This is not what one would imagine at a site that was for a long time revered as a symbol of Americas liberty and the fight against British tyranny. The cave was so symbolic of revolution, in fact, that the French revolutionary Charles Maurice de Talleyrand-Prigord, who contributed to the writing of The Declaration of the Rights of Man (1789), visited it in 1794 and made a very animated and impassioned address in French in relation to [Whalley and Goffe], their amor patriae, and their love of freedom. Goffe went from being apprenticed to a London grocer in 1634 to being one of the most familiar characters in nineteenth-century American literature: a proto-American revolutionary. The regicides became the subject of fascination in many cultural forms, thousands of miles away from, and centuries after, their births. Now comparatively little attention is paid to the regicides in America or to the inscription on the cave in New Haven.

This book plots the rise and decline of the regicides in Americahow and why they were celebrated (or, sometimes, criticized), and how and why their story was manipulated, twisted, and distorted to suit different political sympathies and cultural tastes, across three and a half centuries. Charles Is Killers in America is not simply the story of the regicides on the run, as exciting as their flight may have seemed. Their story carries with it intriguing historical and ideological baggage that continued to be unpacked and repackaged in various cultural forms on both sides of the Atlantic, but especially in America, into the twenty-first century. So this book plots the lives and afterlives of Edward Whalley and William Goffeand, to a lesser extent, John Dixwell, a third regicide in Americafrom their role in the English civil wars to the point at which the Judges Cave turned from historical monument to make-out point. By investigating these microhistorical figures over a long period of cataclysmic change it is possible to inform a number of wider issues: the relationship between crown and colonies in the late seventeenth century; the presence of the English regicide in debates surrounding the American Revolution; and the persistence of the regicides in Americas founding narratives and the forging of a distinct American national identity. We can see how one of the most dramatic moments in British historythe execution of Charles Iwas remembered and represented across the Atlantic over subsequent centuries.

Acknowledgements

I am grateful to the Huntington Library for awarding me Mayers Research Fellowships in 2011 and 2014. The Eatons and Juan Gomez were generous hosts and convivial companions while I researched and wrote in California, while Cory Way, Gay and Alison Amherst, and Tom Vignieri kindly provided accommodation while I worked in Cambridge, Mass., and Boston. I would like to thank Will Capel, Robert Gullifer, William Lawrence, Matthew Neufeld, David Smith, George Southcombe, and William Whyte, and the anonymous readers for Oxford University Press, who read early drafts and made several helpful suggestions to improve them. I also benefited from conversations with Jonathan Fitzgibbons, Tim Harris, and Steve Hindle. Thanks are also due to the staff at the following institutions who have been especially helpful: the Bodleian Library, Oxford; the British Library, London; the Houghton Library, Harvard; Merton College, Oxford; New College, Oxford; the Parliamentary Archives, London; the National Portrait Gallery, London; the New Haven Museum.

Susan Doran, Paulina Kewes, and Desmond King were supportive in helping to find the original manuscript a home. Luciana OFlaherty, Martha Cunneen, and Solene van der Wielen at OUP have been very helpful in guiding the book to publication. Ideas and material from Chapters 4 and 5 were presented at Clive Holmess retirement conference at Lady Margaret Hall, Oxford, in September 2011. I am grateful to the editors of the volume that arose from that conference, George Southcombe and Grant Tapsell, for allowing me to reuse some material here. It was while working on my DPhil under Clive Holmess robust and good-humoured supervision that I came across the printed transcript of the trials of the regicides and Charles Is death warrant, in which I first noticed a regicides disappearing act. Without the expert tutelage of Keith Baker, Adrian Green, and Toby Osborne I would not have been reading for a DPhil at all.