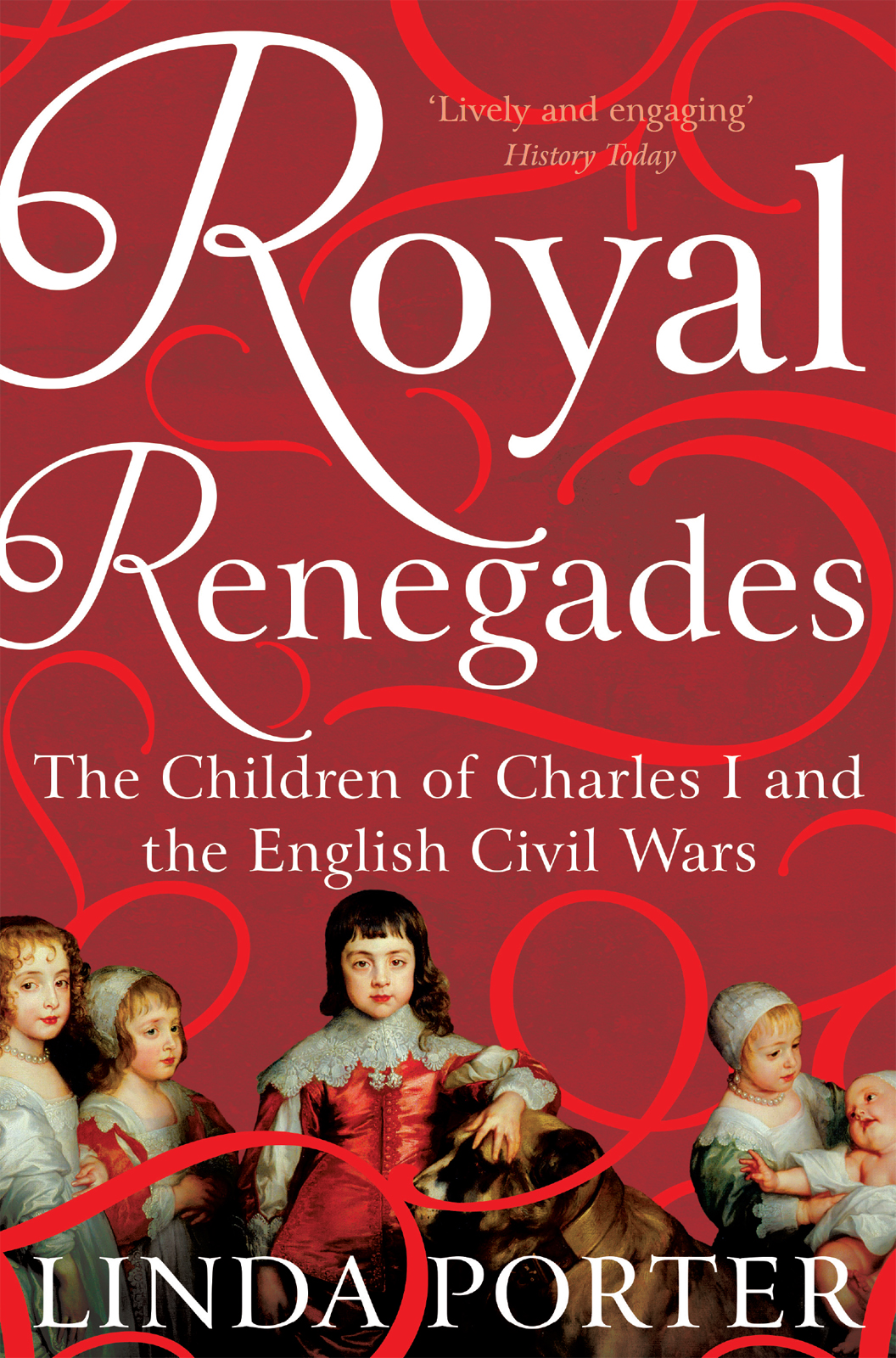

L INDA P ORTER

Royal Renegades

The Children of Charles I and the English Civil Wars

PAN BOOKS

For Emma and Phil

Contents

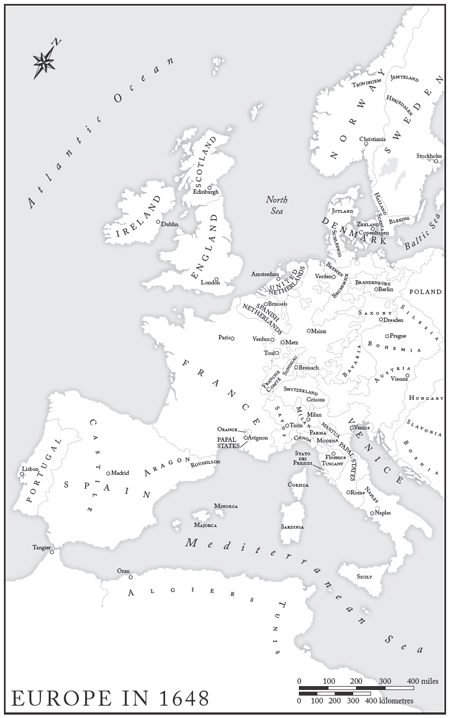

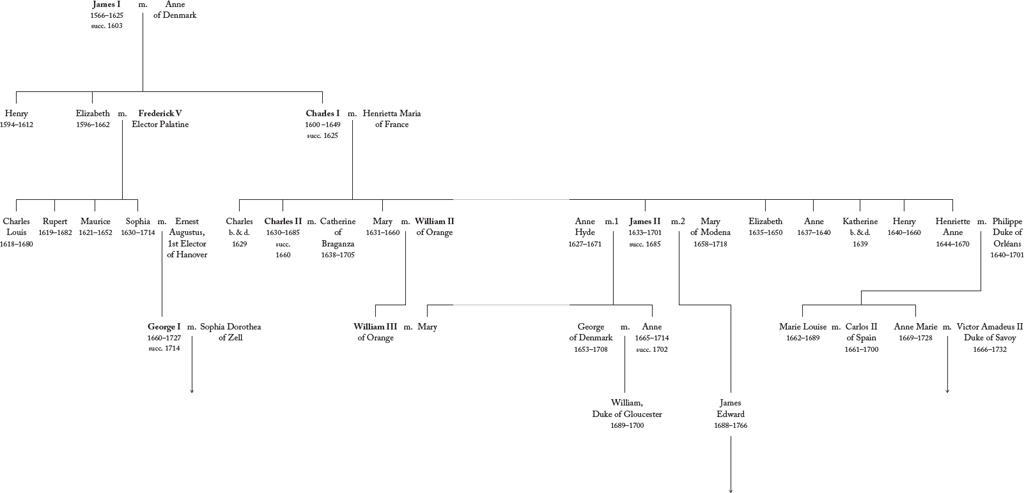

House of Stuart

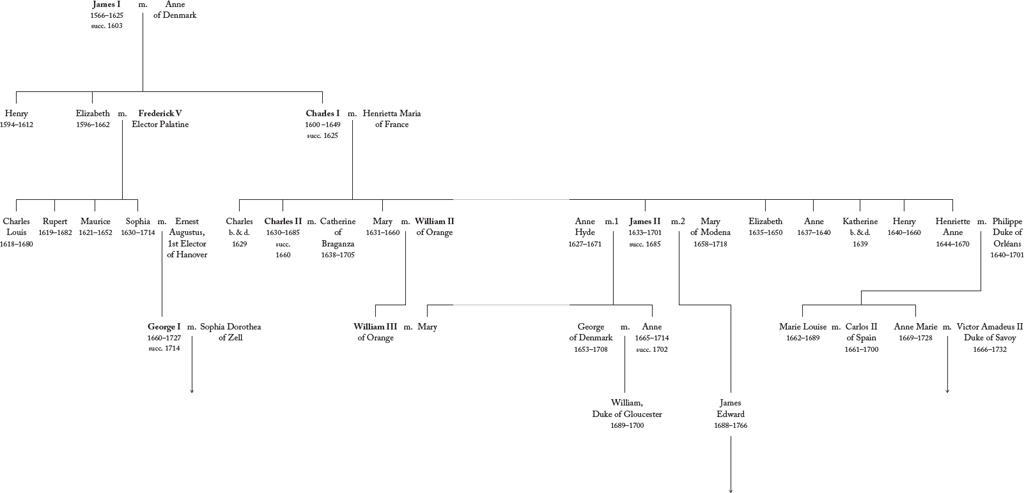

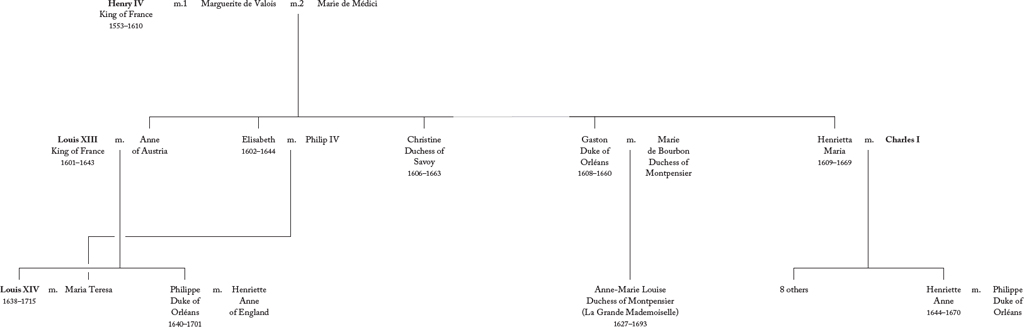

House of Bourbon

Prologue

D OVER , 13 J UNE 1625

He was looking at her feet. She was not quite as short as reports had led him to expect. Could she be wearing heels? French women were renowned for their attention to appearance and detail. They were far less restricted than their counterparts at the stifling Spanish court, where he had gone, in person, to seek his first bride. And this girl was no bashful infanta. The self-possessed teenager who stood before him followed his gaze, speaking up for herself immediately. Sire, she said, raising the hem of her dress, I stand upon mine own feet. I have no help by art. Thus high am I, and neither higher nor lower. Her forthrightness was in contrast to her opening words to him, the carefully considered proprieties of international diplomacy and wifely duty. She had come to this country to be used she assured him. Little did she know that he was far from confident himself.

How could he be? The twenty-five-year-old monarch always known to his father as Baby Charles, the boy who could not walk until he was four because of rickets, who had become the unexpected heir when his gifted elder brother died so suddenly of typhoid, had served a long apprenticeship under the watchful gaze of his clever but unfathomable father, James, the sixth Scottish king to bear that name but the first of England. Now, after just three months on the throne, kingship was as new to this spare, short young man (he was only five feet four inches tall) as the role of queen consort was to this even more diminutive girl of fifteen. Yet the excitement and nervousness that he had felt when he left Canterbury that morning to meet his bride for the first time was alleviated by her winsome mixture of assertion and submission. He took her aside into a private apartment, away from the gaze of their courtiers, so that they could have some time alone together before facing the world as a couple.

There the stress and unfamiliarity of her situation suddenly unnerved her. She confided that she was afraid she would make mistakes and asked him not to be angry with her if she gave offence unintentionally. Acknowledging that her youth and ignorance of English customs might cause difficulties, she asked that he would advise and correct her himself, rather than put her through the humiliation of being upbraided by an intermediary. The king was charmed. He reassured her that she had not fallen into the hands of strangers. God had sent her to be his wife.

The little queen had heard that before, from the priests and nuns who had instructed her in Paris and, most recently, from her ailing mother when they parted at Amiens in northern France. Marie de Mdici, the French queen mother, exhorted her youngest daughter, in a letter she was to keep with her, never to forget that you are a daughter of the Church and to pray daily for her husbands conversion to Catholicism. The king of England saw Gods intentions differently. But for now he embraced her warmly and, her confidence restored, they emerged together so that she could introduce her attendants and followers. There were many of them, for Henriette-Marie de Bourbon had arrived with a retinue worthy of her past as a French princess and her future as queen of England, the wife of Charles Stuart. She would lose the French version of her name quickly, discovering that one of the many disquieting things about her new situation was that no one, including her husband, could take her name seriously. He wanted her to be known as Queen Mary but she has come down to us as Henrietta Maria, one of Englands most notorious queens consort.

The precedents were not encouraging. The last French queen consort of England had been Margaret of Anjou, Shakespeares she-wolf of France, whose desperate attempts to hold the Lancastrian throne for her mentally ill husband, Henry VI, had caused his Yorkist opponents to characterize her as an unnatural termagant during the Wars of the Roses. Commentators in 1625 stayed politely quiet on this point, but there was no escaping the controversy caused by Henrietta Marias religion. The marriage of a Catholic princess to a Protestant monarch was unprecedented in Europe. Pope Urban VIII, whose dispensation was needed, saw in the proposed match the opportunity to alleviate the condition of English Catholics, viewed as an oppressed minority by the papacy. Hopes were even raised of the more distant possibility of restoring England to the old faith. The stipulations of the marriage treaty, signed in Paris on 10 November 1624, meant that the princess brought with her a dowry of 800,000 crowns, which was most welcome, and strict commitments regarding her religious rights and those of her children and household, which were not. Suspension of the penal laws against Catholics was agreed but, given parliamentary opposition, was never, in reality, going to happen. Furthermore, the English had given help over many years to the Huguenots, the French Protestants. The possibility of friction was real even before Henrietta set foot in her new country.

She did, though, definitely want to be queen of England and she had grown impatient during the protracted diplomatic negotiations, despite the charm and encouragement of James Hay, earl of Carlisle, the able Scot sent to talk terms with the chief minister of France, Cardinal Richelieu. Whatever the challenges, Henrietta wanted and expected a crown. In this she was very much her parents daughter. Not that she had known her father, Henry IV of France, the Protestant king of Navarre who had been heir to the throne as the Valois line faded. He had brought to an end the vicious blood-letting of half a century of religious warfare in France in the wonderfully pragmatic declaration that Paris was well worth a Mass. One of Frances most flamboyant and capable kings, his strong hold on the country was brutally ended by the knife of his assassin, Franois Ravaillac, a deranged former monk who got into his carriage on the afternoon of 14 May 1610, stabbing him twice. The king, who is said to have had premonitions of disaster, but was probably just suffering the cares of state, did not survive.

So the regency of a shocked country passed to his wife, the Italian Queen Marie de Mdici, daughter of a famous and still very wealthy house. Despite the fact that she had borne him three sons and two daughters, the couple were seldom on good terms, passing long periods when they would not speak to one another. Henry was twice Maries age, hopelessly given to philandering (there was a growing brood of illegitimate children by various mistresses) and though he was initially pleased by her blonde buxomness and penchant for flashing diamonds, her looks were already on the wrong side of ample when they married. By the time her last child, Henrietta Maria, was born in November 1609, Marie had long since become, in her husbands mind, a fat and fretting irritant who was always badgering him about his mistresses and the fact that, ten years after their marriage, she was still uncrowned. Henry IV publicly acknowledged that he found her boring. Yet he finally gave in about the coronation, and Marie was crowned at the abbey of Saint-Denis, north of Paris, the day before his murder. Despite her constant moaning, it can hardly have been the outcome she had wished for so soon after her day of triumph. Terrified and confused, the royal children spent the night of 14 May under armed guard in the Louvre.