THE ENGLISH CIVIL WAR

The English Civil War 1640-1649

Martyn Bennett

First published 1995

by Pearson Education Limited

Published 2013

by Routledge

2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon OX14 4RN

711 Third Avenue, New York, NY 10017, USA

Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an informa business

Copyright 1995, Taylor & Francis.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers.

Notices

Knowledge and best practice in this field are constantly changing. As new research and experience broaden our understanding, changes in research methods, professional practices, or medical treatment may become necessary.

Practitioners and researchers must always rely on their own experience and knowledge in evaluating and using any information, methods, compounds, or experiments described herein. In using such information or methods they should be mindful of their own safety and the safety of others, including parties for whom they have a professional responsibility.

To the fullest extent of the law, neither the Publisher nor the authors, contributors, or editors, assume any liability for any injury and/or damage to persons or property as a matter of products liability, negligence or otherwise, or from any use or operation of any methods, products, instructions, or ideas contained in the material herein.

ISBN 13:978-0-582-35392-3 (pbk)

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from

th e British Library

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Bennett, Martyn.

The English Civil War, 1640-1649/Martyn Bennett.

p. cm. (Seminar studies in history)

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 0-582-35392-0

1. Great BritainHistoryCivil War, 1642-1649 I. Title.

II. Series.

DA415.B36 1995 94-46858

941.06'2dc20 CIP

Contents

Such is the pace of historical enquiry in the modern world that there is an ever-widening gap between the specialist article or monograph, incorporating the results of current research, and general surveys, which inevitably become out of date. Seminar Studies in History are designed to bridge this gap. The books are written by experts in their field who are not only familiar with the latest research but have often contributed to it. They are frequently revised, in order to take account of new information and interpretations. They provide a selection of documents to illustrate major themes and provoke discussion, and also a guide to further reading. Their aim is to clarify complex issues without over-simplifying them, and to stimulate readers into deepening their knowledge and understanding of major themes and topics.

Readers should note that numbers in square brackets [5] refer them to the corresponding entry in the Bibliography at the end of the book (specific page references are given in italic). A number in square brackets preceded by Doc. [ Doc. 5 ] refers readers to the corresponding item in the Documents section which follows the main text. Words asterisked at first occurrence are defined in the Glossary.

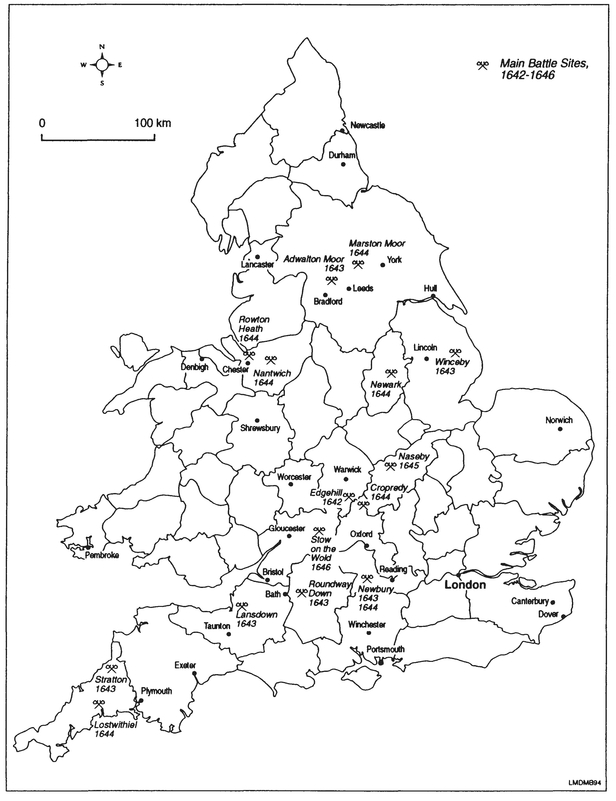

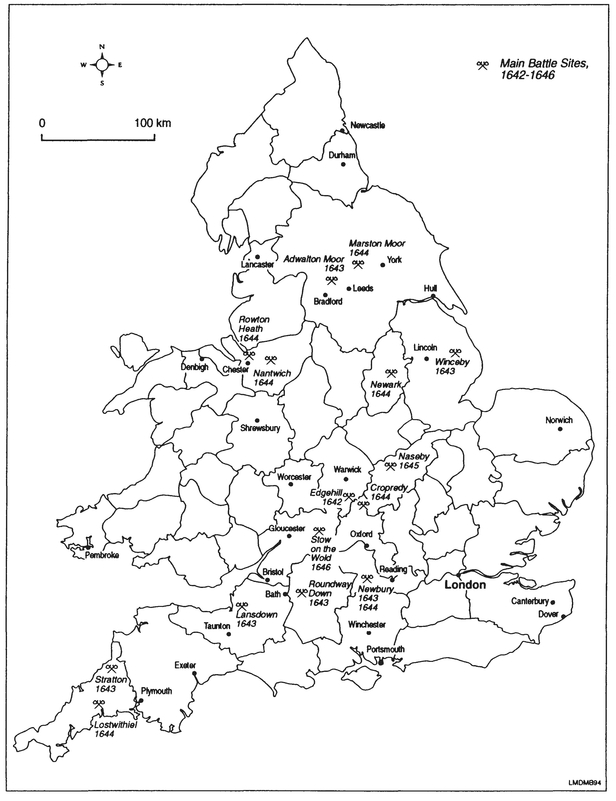

| 1. | Principal battles in England and Wales, 1642-46 |

I would like to thank the General Editor, Roger Lockyer, for his invaluable assistance during the completion of this work. Thanks are also due to Dr Deborah Tyler-Bennett for her comments on the text. I must also thank the staff of the International Studies Department at Nottingham Trent University, and in particular Angela Brown, for their encouragement and interest, and the Faculty of Humanities for allowing me a sabbatical term in which to work on the book. I have also to thank the students of Loughborough University History Department, the Adult Education Department at Leicester University and, in particular, the third-year students in the Humanities Faculty at Nottingham Trent, with whom I have discussed these issues over the past ten years. I must also acknowledge the encouragement of Dr Marilyn Palmer, who first engaged me on such discussions at Loughborough.

Maps by Linda Dawes.

For my father

Principal battles in England and Wales, 1642-46

During the 1630s, Charles I had reigned without the aid of a Parliament, At the same time he had embarked upon major religious changes and sought to create an impression of vigour and power abroad, without becoming embroiled in the wars on the Continent. He had financed his government by means of a series of revamped and exhumed medieval financial measures. The efficacy of his rule dubbed the 'Personal Rule' or the 'Eleven Years' tyranny', depending upon the standpoints of contemporaries and historians has been much debated. Some historians point to the increased effectiveness of the fleet, upon which Charles had spent the income of Ship-money* levies, and the concomitant increase in prestige; others to the unpopularity of the tax and the resistance which all Charles's levies provoked [56; 95; 100; 104]. There can be no doubt that the religious imperialism of King Charles, the attempt to create a uniformity of worship or at least of order in the Church throughout his three kingdoms, was at best provocative, at worst destructive, not only of the religious independence of the three kingdoms, but potentially of the monarchy itself. It was clear to many Scottish people in 1637 that the attempt to impose religious change upon Scotland was misplaced and ill considered; Charles had not only challenged the Scottish Church, the Kirk, but throughout his reign had threatened Scottish law and property rights [91; 104], Such was not clear to Charles, who ignored the resistance which he had provoked from many sections of Scottish society, and saw only a challenge to the elevated view of the monarchy which had led him to refrain from giving any explanation of his motives in his dealings with Scotland during the previous twelve years of his reign. His persistence in stressing his authority and his insensitivity to the popular will in Scotland drove his northern kingdom to take up arms in defence of itself and its Church. The war which followed in 1639 was brief and militarily inconclusive. Both sides showed themselves to be at least superficially willing to prevent further escalation and negotiations were entered into. Whilst this gave rise to a truce - the Pacification of Berwick, June 1639 - it was clear that the basic issues had not been resolved.

The war of 1639 petered out in a way that was not really satisfactory for either side. Charles I was convinced, along with others, that he could have won a military victory with just one more push. The Scots were convinced that Charles had not relinquished what he saw as his right to force a unified religion on his British kingdoms - although this view has been challenged by John Morrill, who sees Charles insisting upon order, and in particular an Episcopalian* order, in the Scottish Kirk (and in Ireland) rather than upon an imperial uniformity across the Churches of all three of his kingdoms [91]. It was Charles's attempt to impose a revised version of the Book of Common Prayer* on Scotland which provoked the revolt which united all sections of Protestant Scotland aside from the minority Episcopalians [57; 74; 107]. The war left Charles in dire financial straits, yet it was in the spirit of a war-maker that Charles summoned his first parliament for eleven years. It met on 13 April 1640 as the Pacification of Berwick finally collapsed and amidst the Crown's chronic financial problems; the projected resumption of war was estimated to require 100,000 per month, which the King did not have. There existed a range of expectations of the new parliament very different from those held by the King. For Charles, it was there solely to support him by providing money in the face of what he portrayed as Scottish rebellion and aggression; he and some members of his Privy Council believed that Parliament would rally behind him and provide the means to continue the war. As encouragement and an example the King had already, through the work of Thomas Wentworth, Lord Deputy in Ireland, gained the vote of subsidies* from the Dublin Parliament. Alongside this Charles had proof positive that the Scots were acting in a traitorous manner: a copy of a letter from prominent Scots to Louis XIII of France, asking for assistance. These circumstances explain why the King, in summoning Parliament, did not - as the Lord Keeper, Baron Finch, explained, 'require their advice but immediate vote of supplies'.