To all who go about the manor of Kentwell

Contents

I

II

III

IV

V

VI

VII

VIII

IX

X

XI

XII

XIII

XIV

XV

XVI

XVII

XVIII

1 England in the Civil War

2 The Battle of Edgehill, 23rd October 1642

(Initial dispositions of both sides based on de Gommes plan and interpretation of texts)

3 I Newbury 1643: Initial Dispositions

4 The Sunderland Campaign, March 1644

5 The Battle of Marston Moor, 2nd July 1644

(Initial dispositions of both armies as depicted by de Gomme and James Lumsden)

6 The Lostwithiel Campaign, 1644

7 II Newbury, 1644: Initial Dispositions

8 The Battle of Naseby, 14th June 1645

(Initial dispositions of both armies as depicted by de Gomme with some assistance from Streeter)

9 The Battle of Dunbar, 3rd September 1650

10 The Battle of Worcester, 3rd September 1651

1 William Barriffe: as the author of The Young Artilleryman , Barriffe was one of the more influential figures in shaping infantry tactics during the English Civil War.

2 Cuirassier equipment as depicted in John Crusos Militarie Instructions for the Cavallrie and cribbed from an earlier work by Wallhausen. A number of individuals and Lifeguard units were equipped as cuirassiers.

3 Sir Thomas, afterwards Lord, Fairfax, Lord General of Parliaments forces.

4 Marston Moor: the Cromwell Monument, marking the approximate area in which he defeated Gorings cavalry in the closing stages of the battle. The Allied front line was probably drawn up along the road in front of the Monument, while the Royalist front line was in the distant hedgerow.

5 Streeters famous engraving of the Battle of Naseby.

6 Although the musket-rest was little used in the Civil War, this illustration from Jacob de Geyhns Exercise of Arms (1607) provides a good picture of a musketeers equipment.

7 The Swedish Brigade.

8 William Cavendish.

9 Marston Moor: the Allied position. The front line was almost certainly drawn up along the road in the foreground and the second line on the low ridge behind. The third line was hidden in the dead ground between this ridge and the higher one crowned by Cromwells Plump, seen in the distance.

10 Cavalry fight as depicted in Crusos Militarie Instructions for the Cavallrie .

All pictures are from the authors collection.

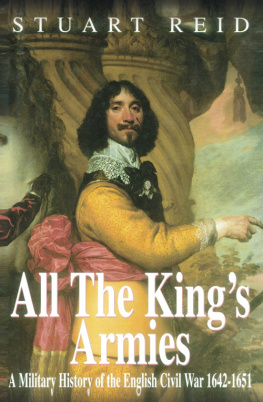

In the year of our Lord 1639 there began an unparalleled conflict in the three kingdoms of Britain. It is popularly known as the English Civil War, but it began first in Scotland, then spread to Ireland and by the time it ended a little over twenty years later, men had died on battlefields as far apart as Caithness and Cornwall, and from Flanders to Virginia.

This book is primarily a military history of the three periods of Civil War fought in England between 1642 and 1651. As such it has two principal objectives. The first and perhaps rather obvious one is to chronicle the military operations and to highlight those actions, battles and campaigns which had a more or less decisive effect upon the course of the war and its ultimate outcome.

Inevitably, decisions have had to be made as to which battles and incidents were important or at the very least merited some examination and which, regrettably, should be omitted or passed over with barely a mention. This is by no means as straightforward a task as it might at first appear, for there is always a tendency among historians to follow the available material and give undue prominence to events which are well documented, irrespective of their actual significance. An excellent case in point might be the action at Chalgrove Field in June 1643, and it is hard to escape a strong suspicion that Sir Ralph (later Lord) Hoptons high reputation owes much more to his very readable memoirs than to his military achievements. On the other hand, while the battle of Marston Moor is well documented, the campaign in Northumberland and the major battle outside Sunderland which preceded it are all but forgotten.

At the same time it has also been necessary in writing this study to adopt a flexible approach to the chronology of events. The war was fought on a number of fronts, and rather than switch from one to another at periodic intervals, it was thought best to follow each campaign from its outset to its end and only to switch at natural break-points. Thus it has been found helpful to treat the war on the central front and the war in the north as two entirely separate conflicts and, for example, to follow the fortunes of the Kings army in 1644 from Cheriton to the Second Battle of Newbury without interruption.

The second objective of this study is to examine the evolution of military doctrine during the war, and to illustrate the way in which military operations were influenced by the availability of arms and ammunition as much as by normal strategic and tactical considerations. An obvious case in point is the increasing reliance on firearms by both sides, which extended to many regiments abandoning pikes altogether before the process was partially reversed in the New Model Army created by Parliament in 1645.

I make no apology for paying scant regard in these pages to the political and religious aspects of the war. This is a study of how the war was fought on the battlefields, and I am pleased to leave discussion of its other aspects to those better qualified than myself.

In closing, it is customary to thank those who have assisted in some manner. They are of course a numerous band, but particular thanks are due to David Ryan, Dr Les Prince, Keith Roberts, John Tincey, John Barratt and all the other participants in the very lively discussion group centred on Partizan Press.

The Beginning of the Wars

As this is a military rather than a social, religious or political history of the English Civil War, it is sufficient for the present purpose to appreciate that the war was essentially a conflict between the forces of absolutism, as represented by the King himself and his Archbishop of Canterbury on the one hand, and the rising power of Parliament and the Protestant middle classes on the other.

In 1603 King James VI of Scotland had the great good fortune to succeed Queen Elizabeth to the English throne as well. Grateful for the opportunity to escape from the endless round of plots, coups and bloody murder which passed for court life in 16th-century Scotland, he hurried southwards with quite indecent haste to assume his inheritance. His new English court was probably just as much inclined to intrigue as his old Scottish one, but at least James now no longer had to contend with pitched battles fought within the confines of the palace itself, and armed gangs unceremoniously bursting into his bedchamber variously intent on intimidation, kidnapping, or even assassination.

As a monarch who had been forced to spend the greater part of his life in constant terror of its violent termination, James naturally warmed to the doctrine of the Divine Right of Kings, and was gratified to find that his new English subjects appeared willing at least to pay lip service to the concept. Nevertheless, he remained astute enough not to push his luck, and the doctrine remained no more than a useful philosophical idea rather than a political reality until the accession of his son, Charles I in 1625.

Unfortunately, Charles not only genuinely believed that he was by God anointed and consequently possessed of something akin to a Protestant equivalent of Papal infallibility, but he also attempted, initially with some success, to put the doctrine into practice by dismissing his less than co-operative Parliament in 1629 and ruling as an absolute monarch for the next eleven years. During this time his most pressing need was to raise sufficient revenue to meet his growing expenditures. Although the courts upheld his royal prerogative to do so without the authority of Parliament the imposition of additional taxes and in particular the extension of Ship-money to inland as well as coastal areas, proved particularly unpopular. Ultimately, however, it was to be his ecclesiastical policies that were his undoing.

Next page