The English Civil War

DAVID CLARK

POCKET ESSENTIALS

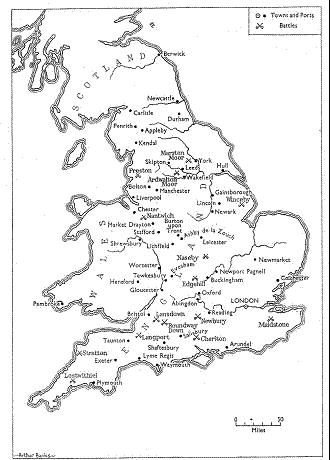

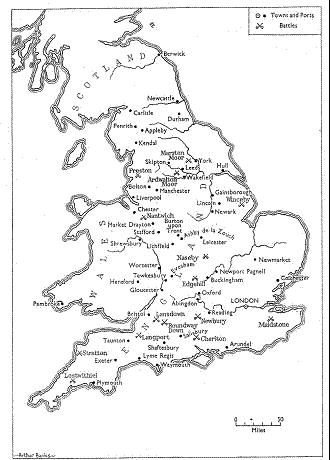

The Principal Battles and Places of the Civil War

Contents

Introduction:

Playing the Game

This Kingdom hath been too long at peace .

Sir Edward Cecil, Viscount Wimbledon

The English Civil War was a conflict in which no one, especially the King, intended to play by the rules and, as such, it was said to mark the end of the age of chivalry. It was strictly a gloves off contest. Many of the leading participants changed sides often for gain and those who remained loyal often went unrewarded by their masters. Those who had been impoverished by their support of Charles I would have to fight tooth and nail to win recognition and recompense from his son at the Restoration.

The objective of Parliament appeared to be simple enough: to capture the King to win. The problem was that the King could only be placed in check; he could not be removed from the board. No one had thought through the implications of the Kings refusal to concede defeat. Sooner or later, it was thought, he had to see sense but, as far as he was concerned, his situation was non-negotiable: he had been appointed by God, and it was no mans business to dispute his Divine Right to rule as he saw fit.

The Kings intransigence, from 1629 onwards, created a tense situation in which something had to give, and everybody wanted a piece of the action. Best placed to take advantage of the crisis were those close to the monarch, favourites such as the Duke of Buckingham had been. They often failed to perform their duties satisfactorily, but this was of secondary importance to their critics, whose main reason for resentment was the fact that they themselves were excluded from taking advantage of opportunities for personal profit afforded by appointment to high office.

Another major player with an eye for the main chance was the Queen. A practising Catholic, she was treated with suspicion by Parliamentarians and Royalists alike, for she would stop at nothing to promote the cause of Rome in her husbands realm. Like Margaret of Anjou, queen to King Henry VI, before her, Henrietta Maria provided the practical initiative that her husband lacked in rallying support for his cause. At one juncture, she toyed with the idea of fielding her own army and a number of women did go so far as to take up arms. However, the heroism of most of the women whose stories have come down to us occurred within a conservative background of domesticity, as exemplified in the devotion to their husbands of Margaret, Duchess of Newcastle and Lucy Hutchinson, wife of Parliamentarian Colonel John Hutchinson, in times of great hardship.

Also close to the King was the Archbishop of Canterbury, William Laud. Just as the movement of a bishop on a chess board is restricted, so the power of senior clergy was limited to matters ecclesiastical. Hearkening back to the days of Cardinal Wolsey, Laud wanted to extend this boundary, and he and his followers developed increasingly influential roles in secular affairs. As far as the Parliamentarians were concerned, episcopacy had to be eliminated. Throughout the war years, rarely did there appear a major piece of legislation which bore no reference to this priority.

In addition to Anglicans and Catholics, there were also the Puritans, for whom the Reformation had not gone far enough. Religion, they argued, was a personal matter, between worshipper and God; there was no need for a priesthood or elaborate rituals. Puritans were particularly active in Parliament and came to be identified as the voice of parliamentary opposition to the crown.

At least many of the knights, or landed gentry, played according to the rules. It was natural that they should do so, for their privileged way of life owed as much to the maintenance of the status quo as did that of the King. By giving their support to Charles, they could look forward to further preferment: knights were elevated to the peerage and peers, in turn, promoted to dukes. Often, their tenants were treated like vassals. When war came, they were expected to follow their lords into battle, much as their ancestors had done in the days of the Wars of the Roses.

The pawns in the game were many. Some 80,000 combatants were killed over the period 164249, most of the bodies being interred in mass graves close to battlefields. The ordinary soldier cared little for whom he fought, and it was common practice for prisoners to agree to change sides and fight for their captors. Non-combatants normally made themselves agreeable to whichever army happened to be in the neighbourhood. Others, in remote locations, appeared not to know that a war was being fought. There is a story of a Long Marston farm labourer who, when asked whom he was for, King or Parliament, allegedly replied: What? Be them two fallen out, then? In the final analysis, any Royalist, regardless of rank, could expect to be sacrificed in order to save the King. Thus, the Earl of Strafford went to the block to mollify the Kings fiercest front-bench critics, while the Marquess of Montrose was condemned to death to facilitate Charles IIs policy of appeasement towards his fathers former enemies.

The key players were those who had no place on the board: the minor gentry who occupied the no-mans land between influence and obscurity, the sons of prosperous merchants or people like Oliver Cromwell, who described himself as by birth a gentleman living neither in any considerable height nor yet in obscurity. They were electable, which is to say that they were able to stand for Parliament. But, once elected, they were unable to exert much influence. Of what use is a parliament which is created for a specific purpose at the behest of the King, and which is condemned to oblivion immediately afterwards? They liked to see themselves as crusaders, waging a holy war on behalf of the people they represented. To an extent this was true but, since most of the population did not have a vote, they represented a minority a bigger minority than the one which was already clinging to power but a minority none the less. When they attained power, they pulled up the ladder very smartly. Everyone seeks an opportunity to strut and fret his hour upon the stage. It was their turn. This was their hour.

163437: The Board

I hope for blood sake he will be welcome, though I believe he will not much trouble the ladies with courting them, nor be thought a very beau garcon... Give your good counsel to Rupert, for he is still a little giddy, though not so much as he has been. I pray tell him when he does ill, for he is good-natured enough, but doth not always think what he should do.

Letter from the Queen of Bohemia to Sir Henry Vane, written prior to Prince Ruperts first visit to England in February 1636

On 28 August 1628, a lieutenant of infantry named John Felton loitered nervously in the Greyhound Inn on Portsmouths High Street. He stood apart from the general conviviality, for he had a very specific purpose in mind. He was there to kill a man. Despite the nature of his calling, he was armed only with a cheap knife, purchased at a cutlers shop on Tower Hill, but this mean weapon would do the job well enough, provided he kept his nerve. His meticulous planning even involved the preparation of a written confession, which he had sewed carefully into his hatband.

Passed over for promotion, owed some 80 pounds in back pay and still suffering from wounds received during an ill-fated expedition to La Rochelle, Felton bore a grudge against the man he considered responsible for all his misfortunes and, indeed, for the woes of the English nation. There were many who would have agreed with him. As his unsuspecting quarry came into view, Felton lunged towards him, drew the knife and drove it deep into his heart. It all happened so quickly that the unfortunate individual could only gasp in astonishment before he fell to the floor, stone dead.

Next page