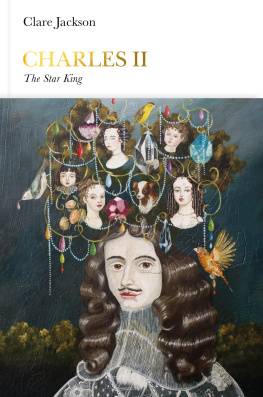

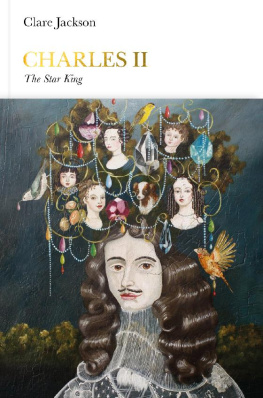

Clare Jackson

CHARLES II

The Star King

Contents

Penguin Monarchs

THE HOUSES OF WESSEX AND DENMARK

| Athelstan | Tom Holland |

| Aethelred the Unready | Richard Abels |

| Cnut | Ryan Lavelle |

| Edward the Confessor | James Campbell |

THE HOUSES OF NORMANDY, BLOIS AND ANJOU

| William I | Marc Morris |

| William II | John Gillingham |

| Henry I | Edmund King |

| Stephen | Carl Watkins |

| Henry II | Richard Barber |

| Richard I | Thomas Asbridge |

| John | Nicholas Vincent |

THE HOUSE OF PLANTAGENET

| Henry III | Stephen Church |

| Edward I | Andy King |

| Edward II | Christopher Given-Wilson |

| Edward III | Jonathan Sumption |

| Richard II | Laura Ashe |

THE HOUSES OF LANCASTER AND YORK

| Henry IV | Catherine Nall |

| Henry V | Anne Curry |

| Henry VI | James Ross |

| Edward IV | A. J. Pollard |

| Edward V | Thomas Penn |

| Richard III | Rosemary Horrox |

THE HOUSE OF TUDOR

| Henry VII | Sean Cunningham |

| Henry VIII | John Guy |

| Edward VI | Stephen Alford |

| Mary I | John Edwards |

| Elizabeth I | Helen Castor |

THE HOUSE OF STUART

| James I | Thomas Cogswell |

| Charles I | Mark Kishlansky |

| [ Cromwell | David Horspool ] |

| Charles II | Clare Jackson |

| James II | David Womersley |

| William III & Mary II | Jonathan Keates |

| Anne | Richard Hewlings |

THE HOUSE OF HANOVER

| George I | Tim Blanning |

| George II | Norman Davies |

| George III | Amanda Foreman |

| George IV | Stella Tillyard |

| William IV | Roger Knight |

| Victoria | Jane Ridley |

THE HOUSES OF SAXE-COBURG & GOTHA AND WINDSOR

| Edward VII | Richard Davenport-Hines |

| George V | David Cannadine |

| Edward VIII | Piers Brendon |

| George VI | Philip Ziegler |

| Elizabeth II | Douglas Hurd |

Note on the Text

In Charles IIs reign, the Julian (Old Style) calendar was in use throughout his three kingdoms of England, Scotland and Ireland; this was ten days behind the Gregorian (New Style) calendar followed in continental Europe. In this book, 1 January is taken as the start of each year, as had been the case in Scotland since 1600, although the English New Year officially started on 25 March. In quotations from primary sources, original orthography has usually been modernized and punctuation amended.

1

The Star King

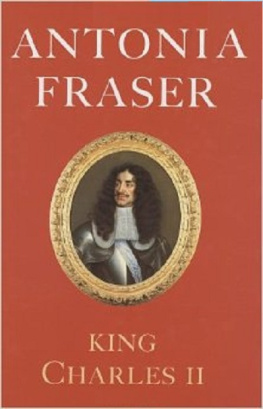

If you were to stop someone on the street and show them images of British monarchs through the ages, Charles II would be among the most recognizable. As the cover of this volume vividly confirms, few kings so readily embody the distinct texture of their period: for many, the Merry Monarch is the Restoration. Lusciously flowing dark ringlets and sumptuously rich Cavalier attire evoke nostalgic impressions of baroque theatricality, swashbuckling extravagance and sexual innuendo. In popular memory, costume dramas and romantic fiction, Charles is affectionately remembered as one of this countrys most charismatic and affable monarchs. He was that rare phenomenon: a king with real star quality.

Precisely because of this correlation, however, few monarchs have acquired so polarized a posthumous reputation. Scholarly opinion has preserved a more equivocal distance, refusing to be seduced by this kings popular appeal. To aspiring biographers, Charles presents a challenge, having repeatedly evaded attempts to capture his personality. Since contemporary accounts of his character yield only a prevailing feeling of unreachability, frustrated historians have reluctantly concluded that the man inside the king

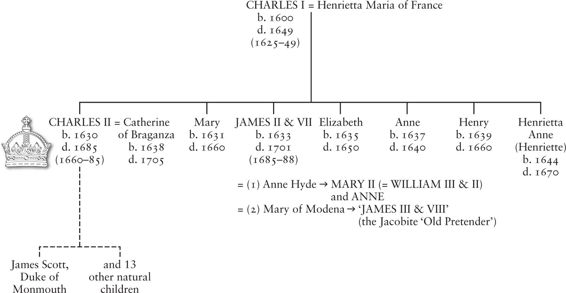

This biography emphasizes instead the vital importance that Charles attached to popular perceptions and public representations of his kingship. No other monarch in British history has succeeded as king after a republican experiment. No other monarch was thus so acutely aware of the extent to which, following a largely peaceful restoration to his English, Scottish and Irish thrones in 1660, his survival as monarch depended on his subjects goodwill after two traumatic decades that had seen prolonged and bloody civil wars, culminating in his fathers execution, and a period of republican and military rule dominated by , followed by four chapters focusing on visual, ceremonial, literary and posthumous depictions of Charles II. This thematic approach reflects not only this particular monarchs preoccupations, but also our own modern obsessions with external appearance and presentational spin.

An appreciation of this kings performance is thus key to probing his personality. Indeed, as an avid supporter of Restoration theatre, Charles was adept at donning different roles, of which being monarch was just one. As an eight-year-old, he had been advised by his governor, William Cavendish, Earl of Newcastle, that a king must know at what time to play the king, and when to qualify it and, during the civil wars, Charles preserved his life precisely by disguising his identity and successfully impersonating his humblest subjects while on the run from Parliamentarian enemies.personal letters, unlike his father or his grandfather James I and VI.

To get to know this king, therefore, readers need to recognize the sheer instability of Charles IIs world. Unpredictability hung in the air of Restoration Britain and little could be taken at face value or guaranteed as permanent. A pervasive mood of secrecy, deception and equivocation meant that even ostensibly devout Anglicans were suspected of being covert papists; parliamentary grants to wage war against France were raised while Charles simultaneously negotiated with the French court for clandestine financial subsidies in return for avoiding war; government spies posed as common highwaymen; and the debauched excesses of Charless aristocratic court threatened to eclipse traditionally plebeian sexual mores.

Charless claim to be the Star King derives, however, from the very day of his birth, 29 May 1630, when a brilliant star shone brightly in the daytime skies over London. The star now thought to be either the planet Venus or the remnants of a supernova was hailed as a significant portent, equivalent to the star that heralded Christs birth in St Matthews Gospel and led the biblical Magi to Bethlehem. As the poet Robert Herrick confirmed: