T HE ENTIRE NATION , even the world, had been fixated for months, but no one could be certain when it would happen.

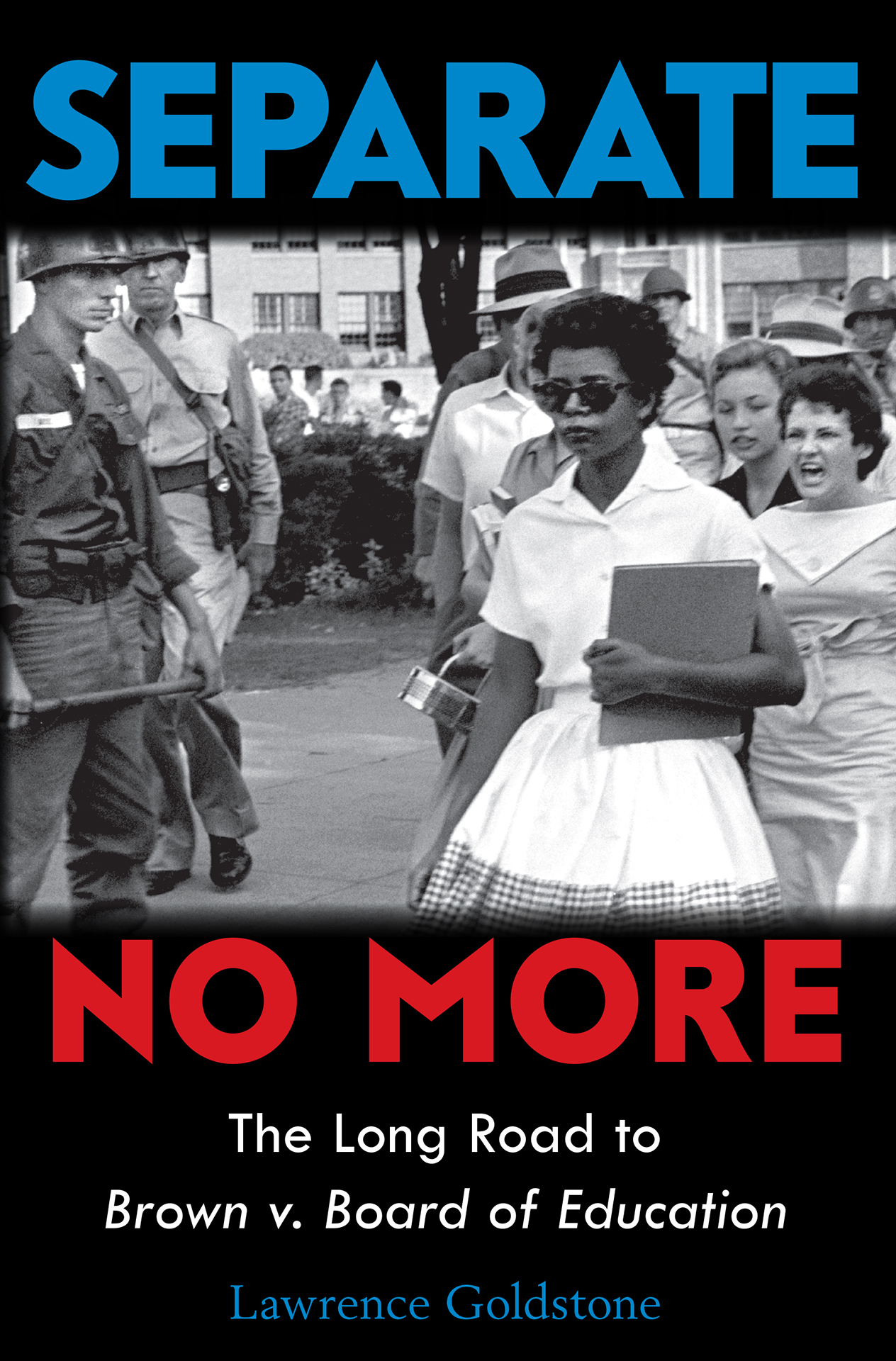

Every Monday in the spring of 1954, in Washington, DC, spectators had jammed into the gallery of the United States Supreme Court to await the decision of the nine justices as to whether the separation of black children from white children in Americas public schools would remain mandated by law. Since 1896, in the landmark case Plessy v. Ferguson , the doctrine of separate but equalstrict racial segregationhad been ruled acceptable under the United States Constitution. But in five cases that had first been heard in December 1952 and then argued again before nine white men in December 1953, a group of lawyers led by an African American, Thurgood Marshall, had attacked that principle, claiming that no arrangement by which Americans were legally separated by race could possibly be consistent with our most sacred founding document. The decision in those lawsuits, grouped together and known by the lead case Oliver Brown et al. v. Board of Education of Topeka, Shawnee County, Kansas , or more simply Brown v. Board of Education , would either cement a system that was the centerpiece of white rule in the Southand parts of the Northor be the first step in breaking down that structure and proclaiming racial equality under the law.

So far, the men and women who had sat breathlessly each week, hoping to witness history, had gone home disappointed. No one but the justices themselves and select court personnel knew which cases would be chosen for any given decision day. (Rulings now are usually issued on Tuesday or Wednesday.) Even after a session began, the roster of cases for that day was not announced, but rather decisions were issued one by one, in whatever order the justices had chosen. Brown had yet to be among them.

Expectation had begun to turn to frustration. Even the reporters who had regularly been a part of the crowds had taken to spending their Mondays in the pressroom, one flight down from the courtroom, content to get their information from printed copies of the opinions rather than hearing them read out in person.

May 17 promised to be no exception. Before the session began, reporters were told it looked like a quiet day. And so, few members of the press were present when the clerk ordered everyone to stand as the justices marched in, led by recently appointed Chief Justice Earl Warren, and then called the court to order with the traditional oration: The Honorable, the Chief Justice and the Associate Justices of the Supreme Court of the United States. Oyez! Oyez! Oyez! All persons having business before the Honorable, the Supreme Court of the United States, are admonished to draw near and give their attention, for the Court is now sitting. God save the United States and this Honorable Court!

After the spectators sat, the justices began the days work. The first case was read, then a second, and then a third. While every case is important, none of these would have anywhere near the national impact of Brown . But then, in the pressroom, the Courts information officer, Banning E. Whittington, suddenly put on his coat and told the reporters, Reading of the segregation decision is about to begin in the courtroom. You will get the opinions up there.

Every reporter bolted out of the room and ran up the stairs.

Brown v. Board of Education is perhaps the most widely recognized Supreme Court case in American history. But for all its renown, most Americans know little about the case itself or the great changes in American society that propelled the Supreme Court to rule as it did.

When Brown was argued, Plessy v. Ferguson was more than a half century old, and the crushing Jim Crow laws that the decision had enabled and affirmed had doomed black people throughout the South to a social, political, and economic environment that was simply slavery in a new form. African Americans were denied even the most fundamental rights of citizenship; were regularly jailed, brutalized, and murdered; and could not effectively access a legal system that bragged hollowly about guaranteeing equal rights to all. To make certain that black Americans would remain apart from and inferior to whites, their children were forced into a two-tiered and wholly unequal system of education.

But after America emerged from the Second World War, change began to press itself on American society. For the first time, many whites began to question why their black fellow citizens were treated as people to be shunned, debased, and denied the same opportunities to succeed as they so freely enjoyed. From the military barracks to the baseball field to the courtroom, African Americans had begun to demonstrate that not only could they match the achievements of whites, but they could often exceed them. Still, as of May 17, 1954, segregation remained the law of the land. On that day, the Supreme Court of the United States would decide if it wished to join the march to equality or attempt to stand in its way. No matter what decision they made, the course of American history would be forever changed.

T HIS BOOK INCLUDES QUOTED MATERIAL FROM PRIMARY SOURCE DOCUMENTS, SOME OF WHICH CONTAINS RACIALLY OFFENSIVE LANGUAGE . T HESE PASSAGES ARE PRESENTED IN THEIR ORIGINAL, UNEDITED FORM IN ORDER TO ACCURATELY REFLECT HISTORY .

O N J UNE 7, 1892, Homer Plessy, a thirty-four-year-old-shoemaker, purchased a first-class ticket on the East Louisiana Railroad for a thirty-mile journey from New Orleans to Covington, Louisiana. Although the light-skinned Plessy appeared to be nothing more than a well-spoken, well-dressed workingman, he was in fact an octoroon , meaning he was one-eighth black. According to an 1890 Louisiana statute, Act 111, known as the Separate Car Law, no one with black blood could ride in railroad cars reserved for whites. Although the law stated that the separate facilities for the two races must be equal, they never were. People of color were required to ride in the smoky, dingy, broken-down car just behind the locomotive, which became known as the Jim Crow car.

Homer Plessy had not wandered into the whites-only car by accident, nor was he unaware that he was forbidden to be there. He had entered intentionally and had been asked to do so by a group called the Citizens Committee to Test the Constitutionality of the Separate Car Law. The group had been founded on September 1, 1891, and consisted of doctors, lawyers, newspaper publishers, and prominent businessmen. Almost all were mixed race. Their leader, Louis Martinet, held degrees from both medical school and law school, and edited a local weekly. They had raised $30,000, a large sum of money in those days, to attempt to have the Separate Car Law overturned by the United States Supreme Court.

Louis Martinet and his fellows were part of the most vibrant and accomplished African American community in the South, and perhaps in the entire nation. Since the early eighteenth century, New Orleans, then under French rule, had boasted a population of educated, able, free black men and sometimes women. They referred to themselves as Black Creoles, or gens de couleur libres (free people of color). These men and women had prospered both before the Civil War and during Reconstruction; they had sent their children to college; they had visited Europe; some had even owned slaves of their own. The number of free black people in Louisiana17,462 in 1850was far greater than in any other Southern state. Fewer than 2,000 lived in neighboring Mississippi.