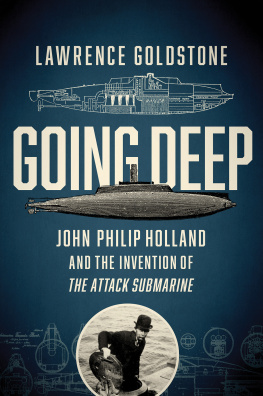

GOING DEEP

Pegasus Books Ltd.

148 W 37th Street, 13th Floor

New York, NY 10018

Copyright 2017 Lawrence Goldstone

First Pegasus Books edition June 2017

Interior design by Maria Fernandez

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in whole or in part without written permission from the publisher, except by reviewers who may quote brief excerpts in connection with a review in a newspaper, magazine, or electronic publication; nor may any part of this book be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or other, without written permission from the publisher.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available.

ISBN: 978-1-68177-429-9

ISBN: 978-1-68177-484-8 (e-book)

Distributed by W. W. Norton & Company, Inc.

www.pegasusbooks.us

To Nancy and Lee

CONTENTS

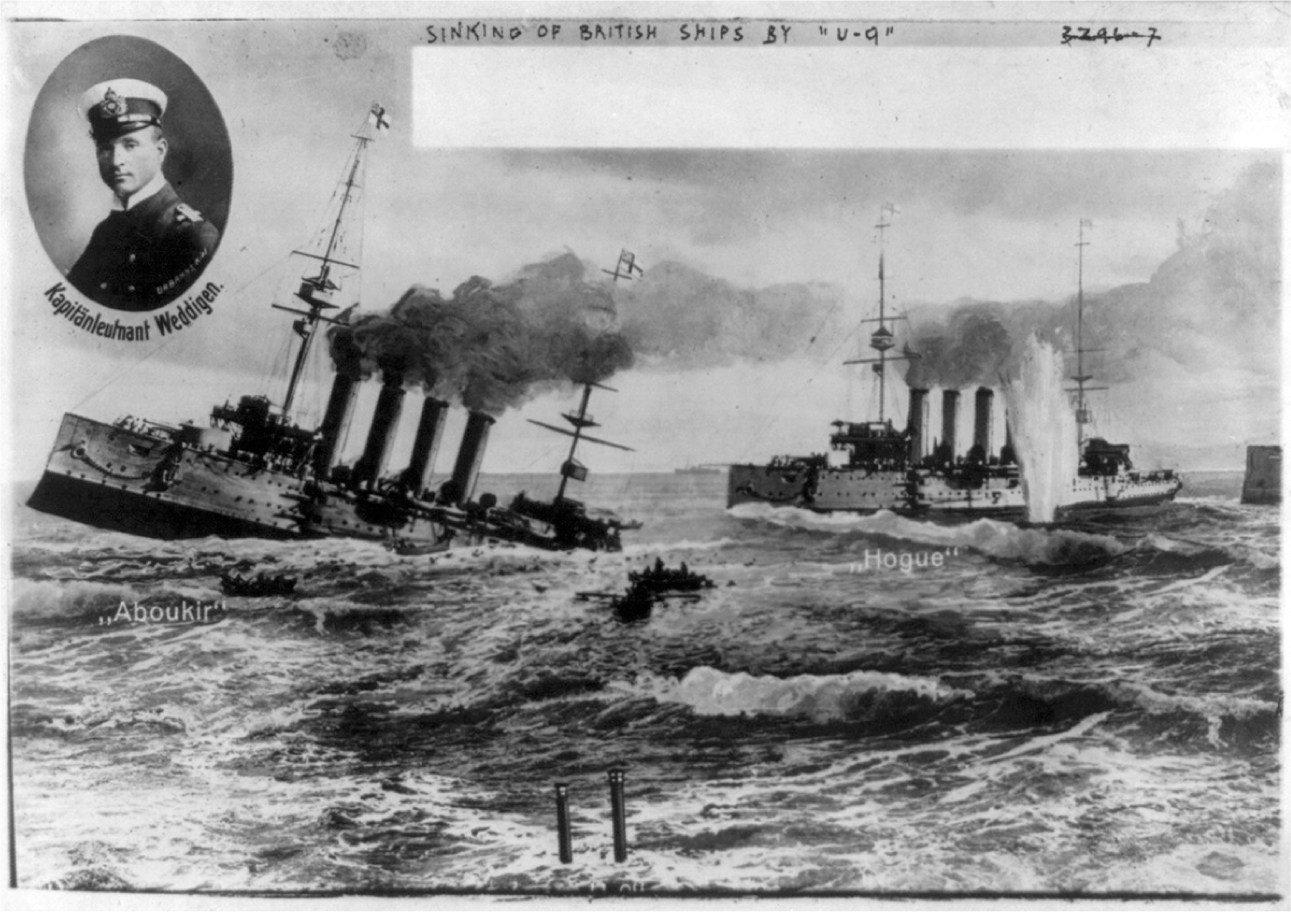

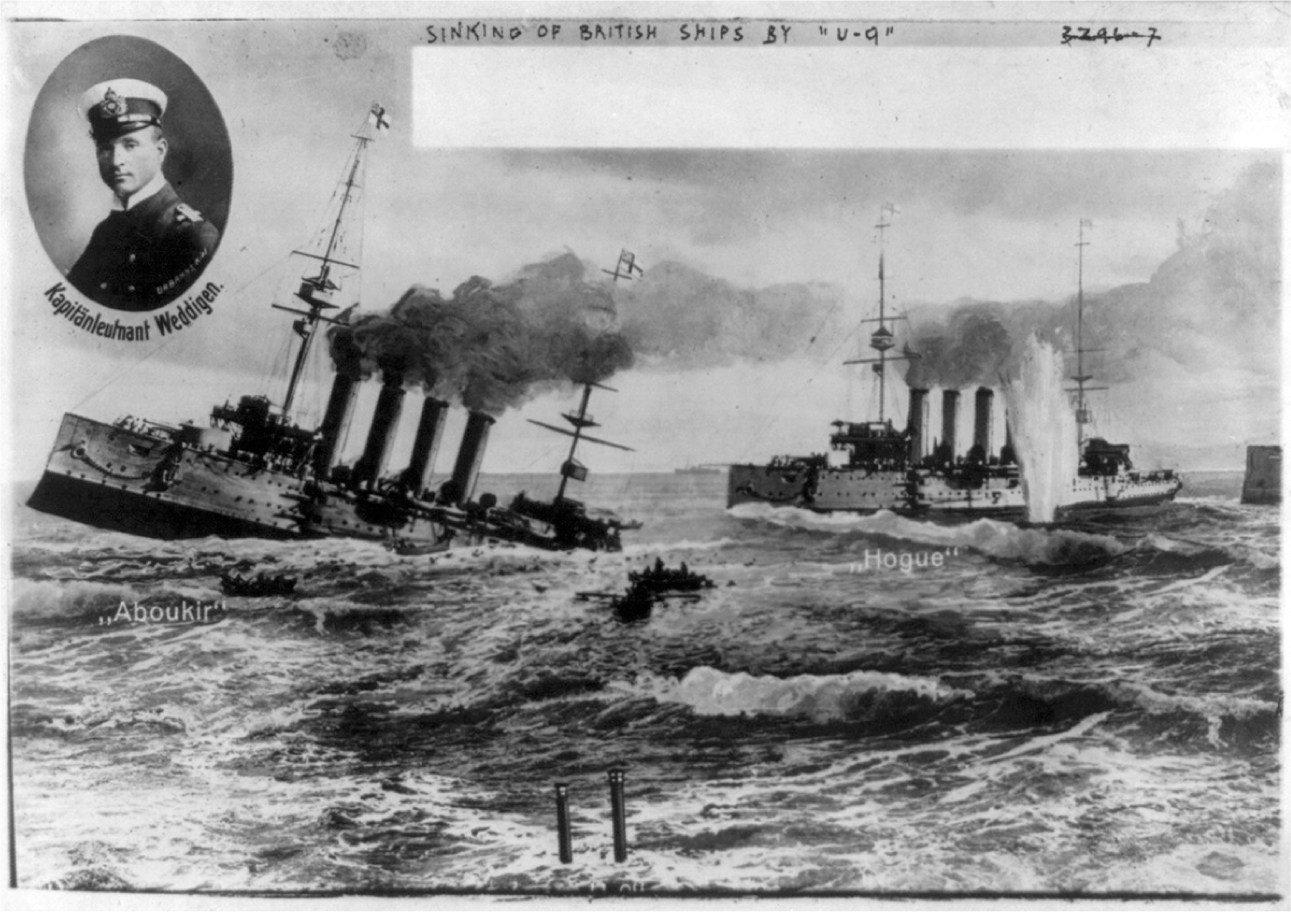

S eptember 22, 1914, 3:00 A.M. Six weeks into a war that was to become the bloodiest in human history. A tentative calm had finally descended on the North Sea after three days of savage storms, and the British Admiralty ordered a resumption of patrols off the coast of Holland. An hour before dawn, three aging battle cruisers were sent out to take positions on the line, three miles apart. While the ships were old, the crews were not. The Aboukir , the Hogue , and the Cressy were part of a five-boat contingent manned mostly by young reservists and thus nicknamed the Live Bait Squadron. They would certainly be so that day. With the seas still rough, the cruisers usual destroyer escort was ordered to remain at anchor.

At 6:30 A.M. , the three ships separated to take up their stations. Almost immediately, a huge explosion shook Aboukir , which was seen to reel violently, and then settle down with a list to port. The two other ships turned at once to steam to her aid. When they had closed sufficiently to lower cutters to pick up survivors, the Hogue to Soon after that, the Cressy exploded amidships and, like the other two, sank almost immediately.

Two Dutch vessels appeared quickly and helped rescue 60 officers and 777 men. But another 60 officers and some 1,399 sailors died in the explosions, were roasted to death, or drowned.

In this singular battle, lasting less than ninety minutes, the three British cruisers had been attacked by a vessel that, until six weeks earlier, had never been employed by the German navy, or, in a real sense, by any navy at all. It sailed not on the sea, but under it.

It was only after the Aboukir and the Hogue had been torn apart that Captain Robert W. Johnson, aboard the Cressy , realized what had befallen his comrades, although too late to save them or himself. According to the official report, five minutes after Captain Johnson maneuvered the ship so as to render assistance to the crews of the Hogue and Aboukir ... a periscope was seen on the starboard quarter, and fire was opened. The track of the torpedo she fired at a range of from 500 to 600 yards was plainly visible, and it struck on the starboard side just before the after bridge.

The periscope belonged to submarine U-9 , commanded by dashing, thirty-two-year-old Kapitnleutnant Otto Weddigen. The boat was 188 feet long and only 19 feet across. Its crew of twenty-six officers and men lived in impossibly cramped conditions, stuffed along with provisions and armaments into a narrow cylinder that provided little room to move and even less to sleep. Fans to circulate the air were so feeble that most of the sailors were left constantly gasping for breath, even when U-9 was running on the surface. Heat from the engines was stifling and sanitary facilities were worse than in a prison. But neither Weddigen nor his crew would ever register a single complaint. They were pioneers, entrusted with a potent new weapon they were certain would be instrumental in their nations victory.

Postcard depicting Weddigens triumph

Weddigen had gained his commission four years earlier, when U-9 first put to sea, and just days before he left on patrol, he had been married to his childhood sweetheart. With the sinking of the Aboukir , Hogue , and Cressy , U-9 s captain became a national hero. I reached the home port on the afternoon of the 23rd, he said later, and on the 24th went to Wilhelmshaven to find that news of my effort had become public. My wife, dry-eyed when I went away, met me with tears. Then I learned that my little vessel and her brave crew had won the plaudit of the Kaiser, who conferred upon each of my co-workers the Iron Cross of the second class and upon me the Iron Crosses of the first and second classes.

In Great Britain, the reaction was far different. Within days, the Admiralty issued a statement: The sinking of the Aboukir was of course an ordinary hazard of patrolling duty. The Hogue and Cressy , however, were sunk because they proceeded to the assistance of their consort, and remained with engines stopped, endeavoring to save life, thus presenting an easy target to further submarine attacks. The natural promptings of humanity have in this case led to heavy losses, which would have been avoided by a strict adhesion to military consideration. Modern naval war is presenting us with so many new and strange situations that an error of judgment of this character is pardonable.

War on the high seas had changed forever.

On August 12, 1914, roughly six weeks before Weddigen fired his torpedoes, John Philip Holland died of pneumonia at his home at 38 Newton Street in Newark, New Jersey. Holland, a former schoolteacher and once a choirmaster at his local church, was by all accounts a gentle, modest man, and he rated only a brief obituary in local newspapers. He had been born seventy-three years earlier on the west coast of Ireland, in County Clare. Gaelic was the chosen language in the Holland home, since his mother spoke no English. John had been a sickly child, plagued with chronic respiratory problems that followed him into adulthood and would eventually kill him. Because of his delicate health, he had been sent to the Christian Brothers for his education; he stayed on to teach but left the order just before he was to take his final vows. Shortly afterward, he immigrated to the United States, where he spent the remainder of his life. While he never waned in his passion for Ireland, Holland chose to be buried in his adopted homeland rather than the one of his birth.

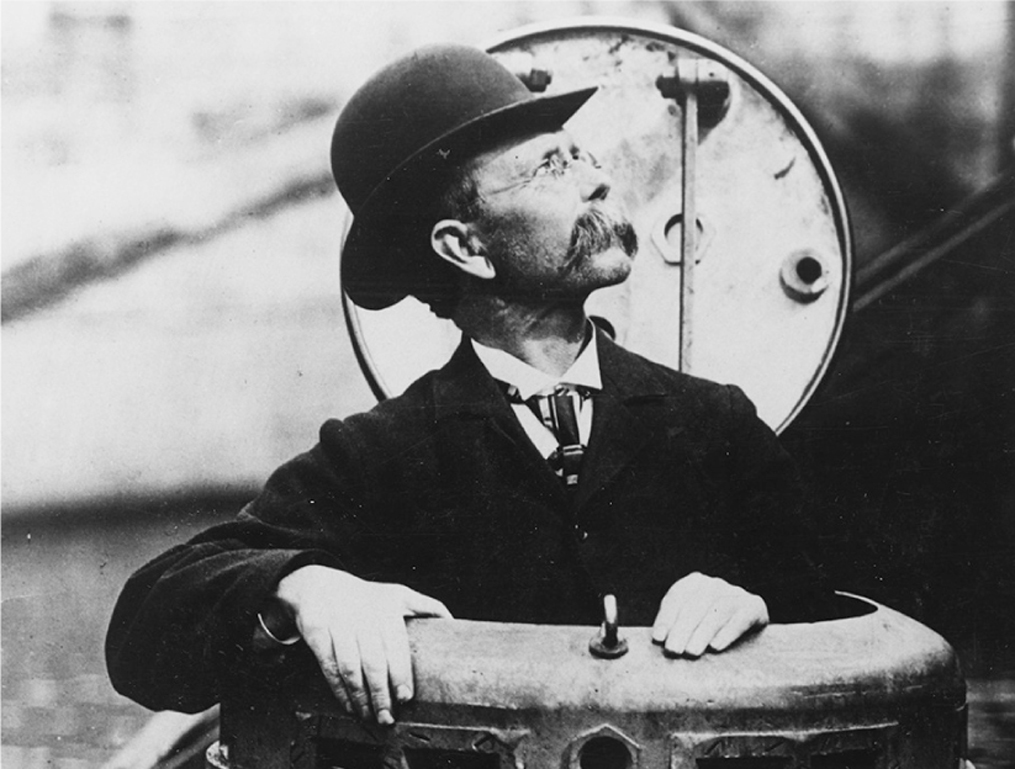

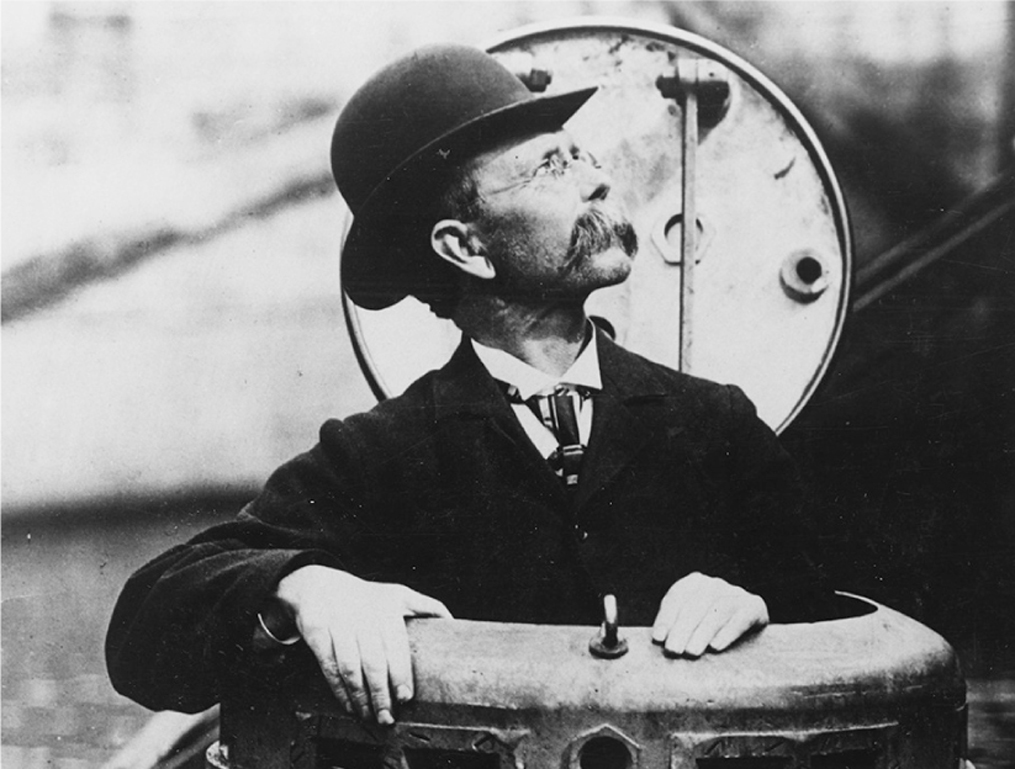

John Holland emerging from one of his creations.

Although he had died in near obscurity, John Holland cast a shadow over those fifteen hundred deaths in the North Sea and also the thousands of other encounters between traditional warships and this new instrument of stealth and surprise. He was then and still widely is considered the father of the modern submarine, but he would never know that he had helped create one of the defining killing machines of two world wars.

For millennia, the ocean depths have held as great a fascination as the heavens, and undersea travel has been a fantasy equal to the dream of flight. Just as virtually every society created fanciful machines to allow men to soar into the sky, there were similar fancies about devices that could sustain humans under the water. Leonardo, as did many of the greatest scientific thinkers, theorized about both but failed to bring either to fruition. But, like Wilbur and Orville Wright, who had also followed in many of the same footsteps, John Holland did not fail. For decades, combining insight with perseverance, and enduring frustration, trial, and much error, Holland turned imagination into reality. And, as with every journey of exploration, death waited constantly in the wings.

Next page