Transcriber's Notes:

The corrections listed in the "ERRATA" paragraph have been made.

Further changes in the text are marked with a dashed blue line ; the original text is displayed when the mouse cursor hovers over it.

Greek words are marked with a dashed gray line ; a transcription is displayed.

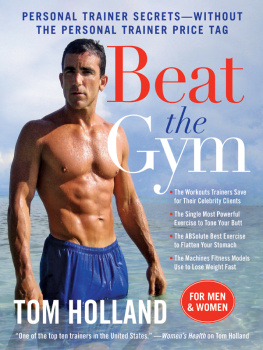

William Pitt, in later life. (From a painting by Hoppner in the National Portrait Gallery)

WILLIAM PITT

AND

THE GREAT WAR

BY

J. HOLLAND ROSE, Litt.D.

England and France have held in their hands the fate of the world, especially that of European civilization. How much harm we have done one another: how much good we might have done!Napoleon to Colonel Wilks, 20th April 1816.

Emblem

LONDON

G. BELL AND SONS, LTD.

1911

CHISWICK PRESS: CHARLES WHITTINGHAM AND CO.

TOOKS COURT, CHANCERY LANE, LONDON.

PREFACE

In the former volume, entitled "William Pitt and National Revival," I sought to trace the career of Pitt the Younger up to the year 1791. Until then he was occupied almost entirely with attempts to repair the evils arising out of the old order of things. Retrenchment and Reform were his first watchwords; and though in the year 1785 he failed in his efforts to renovate the life of Parliament and to improve the fiscal relations with Ireland, yet his domestic policy in the main achieved a surprising success. Scarcely less eminent, though far less known, were his services in the sphere of diplomacy. In the year 1783, when he became First Lord of the Treasury and Chancellor of the Exchequer, nearly half of the British Empire was torn away, and the remainder seemed to be at the mercy of the allied Houses of Bourbon. France, enjoying the alliance of Spain and Austria and the diplomatic wooings of Catharine II and Frederick the Great, gave the law to Europe.

By the year 1790 all had changed. In 1787 Pitt supported Frederick William II of Prussia in overthrowing French supremacy in the Dutch Netherlands; and a year later he framed with those two States an alliance which not only dictated terms to Austria at the Congress of Reichenbach but also compelled her to forego her far-reaching schemes on the lower Danube, and to restore the status quo in Central Europe and in her Belgian provinces. British policy triumphed over that of Spain in the Nootka Sound dispute of the year 1790, thereby securing for the Empire the coast of what is now British Columbia; it also saved Sweden from a position of acute danger; and Pitt cherished the hope of forming a league of the smaller States, including the Dutch Republic, Denmark, Sweden, Poland, and, if possible, Turkey, which, with support from Great Britain and Prussia, would withstand the almost revolutionary schemes of the Russian and Austrian Courts.

These larger aims were unattainable. The duplicity of the Court of Berlin, the triumphs of the Russian arms on the Danube, and changes in the general diplomatic situation, enabled Catharine II to foil the efforts of Pitt in 1791. She worked her will on the Turks and not long after on the Poles; Sweden came to an understanding with her; and Prussia, slighting the British alliance, drew near to the new Hapsburg Sovereign, Leopold II. In fact, the events of the French Revolution in the year 1791 served to focus attention more and more upon Paris; and monarchs who had thought of little but the conquest or partition of weaker States now talked of a crusade to restore order at Paris, with Gustavus III of Sweden as the new Cur de Lion. This occidentation of diplomacy became pronounced at the time of the attempted escape of Louis XVI and Marie Antoinette to the eastern frontier at Midsummer 1791. Their capture at Varennes and their ignominious return to Paris are in several respects the central event of the French Revolution. The incident aroused both democrats and royalists to a fury which foredoomed to failure all attempts at compromise between the old order and the new. The fierceness of the strife in France incited monarchists in all lands to importunate demands for the extirpation of "the French plague"; and hence were set in motion forces which Pitt vainly strove to curb. War soon broke out in Central Europe. His endeavours to localize it were fruitless; and thenceforth his chief task was to bring to an honourable close a conflict which he had not sought. It is therefore fitting that this study of the latter, less felicitous, but equally glorious part of his career should begin with a survey of the situation in Great Britain and on the Continent at the time of the incident at Varennes which opened a new chapter in the history of Europe.

In the present volume I have sought to narrate faithfully and as fully as is possible the story of the dispute with France, the chief episodes of the war, and the varied influences which it exerted upon political developments in these islands, including the early Radical movement, the Irish Rebellion of 1798, and other events which brought about the Union of the British and Irish Parliaments, the break up of the great national party at Westminster in 1801, and the collapse of the strength of Pitt early in the course of the struggle with the concentrated might of Napoleon.

That mighty drama dwarfs the actors. Even the French Emperor could not sustain the rle which he aspired to play, and, failing to discern the signs of the times, was whirled aside by the forces which he claimed to control. Is it surprising that Pitt, more slightly endowed by nature, and beset by the many limitations which hampered the advisers of George III, should have sunk beneath burdens such as no other English statesman has been called upon to bear? The success or failure of such a career is, however, to be measured by the final success or failure of his policy; and in this respect, as I have shown, the victor in the Great War was not Napoleon but Pitt.

To that high enterprise he consecrated all the powers of his being. His public life is everything; his private life, unfortunately, counts for little. The materials for reconstructing it are meagre. I have been able here and there to throw new light on his friendships, difficulties, trials, and, in particular, on the love episode of the year 1797. But in the main the story of the life of Pitt must soar high above the club and the salon to

... the toppling heights of Duty scaled.

Again I must express my hearty thanks to those who have generously placed at my disposal new materials of great value, especially to His Grace the Duke of Portland, the Earl of Harrowby, Earl Stanhope, E. G. Pretyman, Esq., M.P., and A. M. Broadley, Esq.; also to the Rev. William Hunt, D.Litt., and Colonel E. M. Lloyd, late R.E., for valuable advice tendered during the correction of the proofs, and to Mr. Hubert Hall of H.M. Public Record Office for assistance during my researches there. I am also indebted to Lord Auckland and to Messrs. Longmans for permission to reproduce the miniature of the Hon. Miss Eden which appeared in Lord Ashbourne's "Pitt, Some Chapters of his Life and Times," and to Mr. and Mrs. Doulton for permission to my daughter to make the sketch of Bowling Green House, the last residence of Pitt, which is reproduced near the end of this volume. In the preface to the former volume I expressed my acknowledgements to recent works bearing on this subject; and I need only add that numerous new letters of George III, Pitt, Grenville, Burke, Canning, etc., which could only be referred to here, will be published in a work entitled "Pitt and Napoleon Miscellanies," including also essays and notes.

J. H. R.

March 1911.