CONTENTS

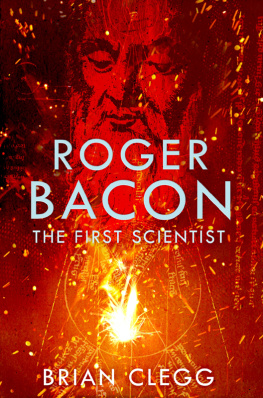

CHAPTER ONE

Turmoil and Opportunity: Roger Bacon's England

CHAPTER TWO

Logic and Mysticism: Aristotle, Plato, and Christianity

CHAPTER THREE

Logic and Theology: The Evolution of Scholasticism

CHAPTER FOUR

Dogma, Drink, and Dissent: The University of Paris

CHAPTER FIVE

Rebels in Gray Robes: Oxford

CHAPTER SIX

Science Goes Mainstream: The Rise of Albertus Magnus

CHAPTER SEVEN

The Dumb Ox: Thomas Aquinas

CHAPTER EIGHT

The Miraculous Doctor: Roger Bacon at Oxford

CHAPTER NINE

Autocracy in the Order of St. Francis

CHAPTER TEN

Theology Becomes a Science: The Logic of Thomas Aquinas

CHAPTER ELEVEN

The Great Work

CHAPTER TWELVE

Seeing the Future: The Scientia Experimentalis of Roger Bacon

CHAPTER THIRTEEN

Knowledge Suppressed: The Conservatives Respond

CHAPTER FOURTEEN

Enigmas and Espionage: The Strange Journey of Dr. Dee

CHAPTER FIFTEEN

Brilliant Braggart: Francis Bacon

CHAPTER SIXTEEN

The Trail of the Cipher Manuscript

CHAPTER SEVENTEEN

The Making of the Most Mysterious Manuscript in the World

CHAPTER EIGHTEEN

MS 408

CHAPTER NINETEEN

The Unfinished Legacy of Roger Bacon

TO EMILY

AND TO JED

Sad it is to think of what this great man might have given to the world... He held the key to treasures which would have freed mankind from ages of error and misery. With his discoveries as a basis, with his method as a guide, what might not the world have gained! Thousands of precious lives shall be lost, tens of thousands shall suffer discomfort, privation, sickness, poverty, ignorance, for lack of discoveries and methods which... would now be blessing the earth.

ANDREW DICKSON WHITE

Cofounder, Cornell University, 1895

Man, in so far as he is man, has two things, bodily strength and virtues, and in these he can be forced in many things; but he has also strength and virtues of soul. In these he can be neither led nor forced, but only hindered. And so, if a thousand times he is thrown into prison, never can he go against his will unless the will succumbs.

ROGER BACON

Opus Tertium, 1268

Prologue

IN LATE FALL OF 1912, Wilfrid Michael Voynich, a prominent London book dealer on a buying expedition to the continent, chanced upon a collection of rare illuminated manuscripts stuffed into some old wooden chests at Villa Mondragone, a secluded castle in Frascati, Italy. The castle was then the home of a Jesuit school, but the collection had evidently been hastily secreted a century earlier when Napolon's voracious armies were hurling Europe into war and chaos. Many of the manuscripts were marked as belonging to Pierre-Jean Beckx, the 22nd general of the Society of Jesus, who had died twenty-five years before. They also held the seals of the dukes of Ferarra, Parma, and Modena, some of Italy's preeminent noble families.

The school was badly in need of funds, and Voynich knew that he could have his pick of the lot. Aware that there was a strong market for illuminated manuscripts back in England, as they combined the lure of antiquity with rich decorations in brilliant blues, reds, and golds, he pored eagerly through the chests, sorting out the most valuable and those in the best condition. There was one volume, however, that intrigued him precisely because of its lack of beauty. Voynich himself described it as an ugly duckling. It was just over two hundred pages and small, only six by nine inches, about the size of a current-day hardcover. The pages were vellum and the cover was blank. No title or author's name was visible anywhere. There was a letter attached, on which was written a date1665 or 1666, Voynich couldn't be surebut he knew immediately from looking at the script and the style of the writing that the manuscript itself was actually much older.

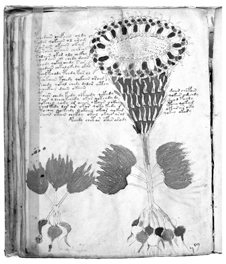

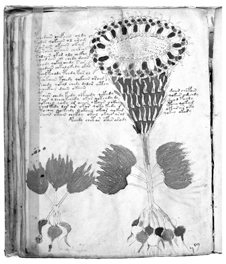

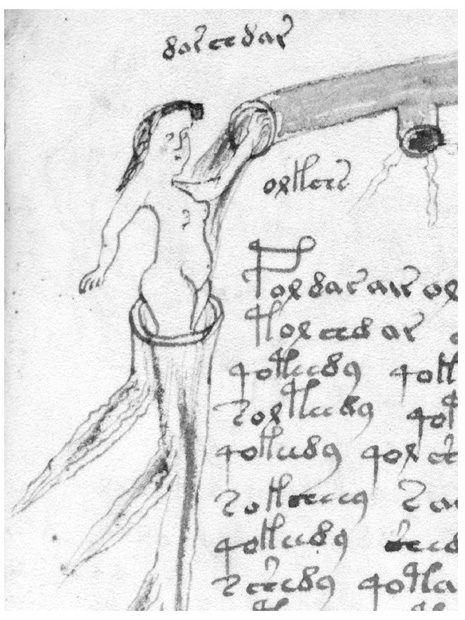

A plant illustration from the Voynich manuscriptBEINECKE RARE BOOK AND MANUSCRIPT LIBRARY, YALE UNIVERSITY

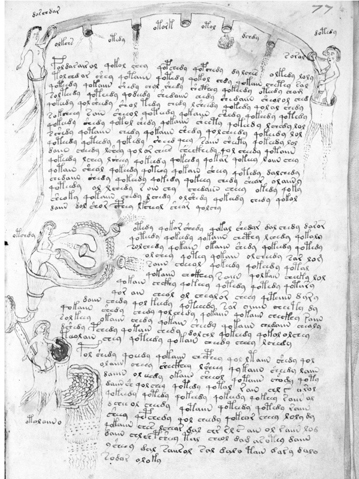

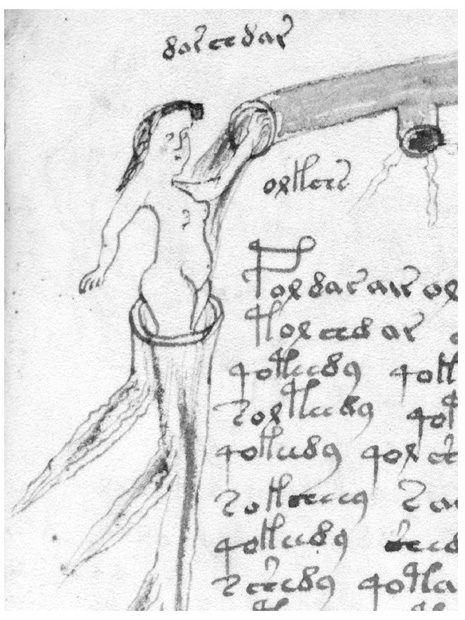

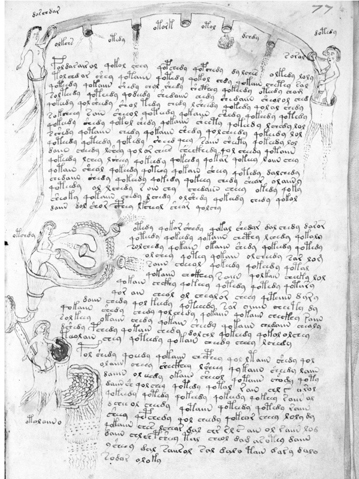

What attracted his attention even more than the text were the illustrations that appeared on almost every pagesometimes in the margins, sometimes in the body of the work. There were hundreds of themexotic-looking plants, quaint astronomical and astrological symbols and charts, and, most bizarre, strings of tiny naked women cavorting in a variety of fountains, waterfalls, and pools. The work appeared to be some sort of encyclopedia of natural science, possibly for use in the practice of medicine. Examining the vellum pages, the calligraphy, the drawings, and the pigments used, Voynich, an expert medievalist, dated the manuscript as late thirteenth century. However, when he perused the odd cursive script itself, he realized that it wasn't Latin, or any other known language for that matter. He could make no sense at all of what was written. With some further examination, he discovered whythe entire manuscript was in cipher.

An example of Voynich scriptBEINECKE RARE BOOK AND MANUSCRIPT LIBRARY, YALE UNIVERSITY

Detail from a Voynich manuscript pageBEINECKE RARE BOOK AND MANUSCRIPT LIBRARY, YALE UNIVERSITY

No thirteenth-century manuscript of this length and detail written in cipher had ever been found before, and Voynich knew that he had stumbled upon something of exceptional importance. The sense of intrigue fascinated him as well. The knowledge had evidently been meant to be hidden. But why? What was there in these drawings of bathing women and lush plants that posed a threat to the author or to the intended reader? Or had the author taken these precautions because he feared repercussions if his book fell into the wrong hands?

Wilfrid Voynich was no stranger to conspiracy. He had been born in Lithuania in 1865, the son of Polish aristocracy. He attended the universities of Warsaw and Moscow, where he fell in with the Russian anarchist Sergius Stepniak. Stepniak, who was subsequently arrested and imprisoned for attempting to assassinate the chief of the Russian secret police, eventually escaped and fled to England. Stepniak's anarchist movement had a great influence on Lenin's older brother Alexandr, who was caught in a similar plot to assassinate the tsar and was executed in 1888.

Next page