Lawrence Goldstone - Stolen Justice: The Struggle for African American Voting Rights

Here you can read online Lawrence Goldstone - Stolen Justice: The Struggle for African American Voting Rights full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 2019, publisher: Scholastic Inc., genre: Politics. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:Stolen Justice: The Struggle for African American Voting Rights

- Author:

- Publisher:Scholastic Inc.

- Genre:

- Year:2019

- Rating:4 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Stolen Justice: The Struggle for African American Voting Rights: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "Stolen Justice: The Struggle for African American Voting Rights" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

Stolen Justice: The Struggle for African American Voting Rights — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "Stolen Justice: The Struggle for African American Voting Rights" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Contents

A NOTE TO READERS:

This book includes quoted material from primary source documents, some of which contains racially offensive language. These passages are presented in their original, unedited form in order to accurately reflect history.

TO NANCY AND LEE

M ARTIN L UTHER K ING , J R ., gave his first address at the Lincoln Memorial during the Prayer Pilgrimage for Freedom on May 17, 1957. In this speech, he argued that the betrayal of disenfranchised Americans offered the best argument for why the struggle for voting rights is so essential for economic and social justice. King declared, Give us the ballot, and we will no longer have to worry the federal government about our basic rights. In the following years, the modern civil rights movement continued its struggle for voting rights. By April 1964, Malcom X angrily expressed the frustration that many felt by the lack of progress. Ominously, he warned, Itll be the ballot or the bullet. Indeed, by 1968, both Malcolm X and King had been assassinated, but it was Kings vision of justice that came to be broadly accepted. In early 1964, the overwhelming majority of states approved the Twenty-Fourth Amendment to the Constitution, which banned the poll tax, thus finally barring economic barriers to voting. Later that year, Congress enacted the Civil Rights Act of 1964 with a comprehensive Voting Rights Act to follow in 1965.

After providing a concise and beautifully written history of enfranchisement in the United States of America, Stolen Justice: The Struggle for African American Voting Rights details the many ways in which voting rights were systematically denied to African Americans. Beginning this history with an account of voting privileges in the early days of the republic, Lawrence Goldstone provides a lively account of the conflicts between the Founding Fathers in their fashioning of electoral processes. To be sure, voting was a state matter, resulting in a patchwork of different rules and regimes. In all cases, slaves were excluded, but in these early days, free men of color were allowed to vote in a surprising number of states, North and South. However, the rollback was swift, especially in the South, and as the Union expanded, fewer states offered voting rights to nonwhites. Eventually, even states in the North restricted voting rights to white men. As Goldstone explains, by 1860, only a handful of Northern states allowed men of color to vote. That year New Yorkers defeated an effort to remove a property qualification that applied only to black voters. As a result, only 6 percent of free blacks in the North were registered to vote in the antebellum era.

In Stolen Justice , Goldstone describes the forces that led to the Reconstruction Acts of 18671868 and the brief period in which the vote was extended to all male freedmen over twenty-one years of age. I have seldom seen such a clear and straightforward description of the passage of the Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amendments as is presented in this book. Aiding in his historical account, Goldstone has added illustrations, photographs, and a remarkably helpful glossary of terms. Of course, the majority of Stolen Justice is concerned with the almost immediate attacks on the rights of African Americans following the Civil War. From the violence that began with the founding of the Ku Klux Klan within a year of Lees surrender at Appomattox to the judicial rulings that chipped away at voting rights promised in the Fifteenth Amendment, Stolen Justice charts the victories of the movement to codify white supremacy in the American South. In his consideration of the judicial challenges to the Fourteenth Amendment, Goldstone begins with the compelling story of the Louisiana Slaughter-House Cases , in which the seemingly banal problem of where New Orleans could locate butchers ended up shifting power away from federal protections and toward state rights. Other surprising cases are cited in this volume, including Strauder v. West Virginia (1880), in which decisions about the racial makeup of a jury began with the case of a confessed ax murderer. In every topic cited in Stolen Justice , the author infuses his history with vibrant personalities, fascinating details, and outrage at racial injustice.

In the very divisive political period in which we find ourselves, it is important to remember the critical importance of voting rights for all Americans. Contemporary attempts to rig voting outcomes including extreme gerrymandering of state legislative and congressional district lines, the enactment of harshly restrictive voter ID laws, draconian restraints on early voting, and the purging of voter rolls should alarm all concerned citizens. Stolen Justice reminds us of our ongoing responsibility to protect voting rights.

Dr. Henry Louis Gates, Jr.

Director of the Hutchins Center

for African & African American Research

Harvard University

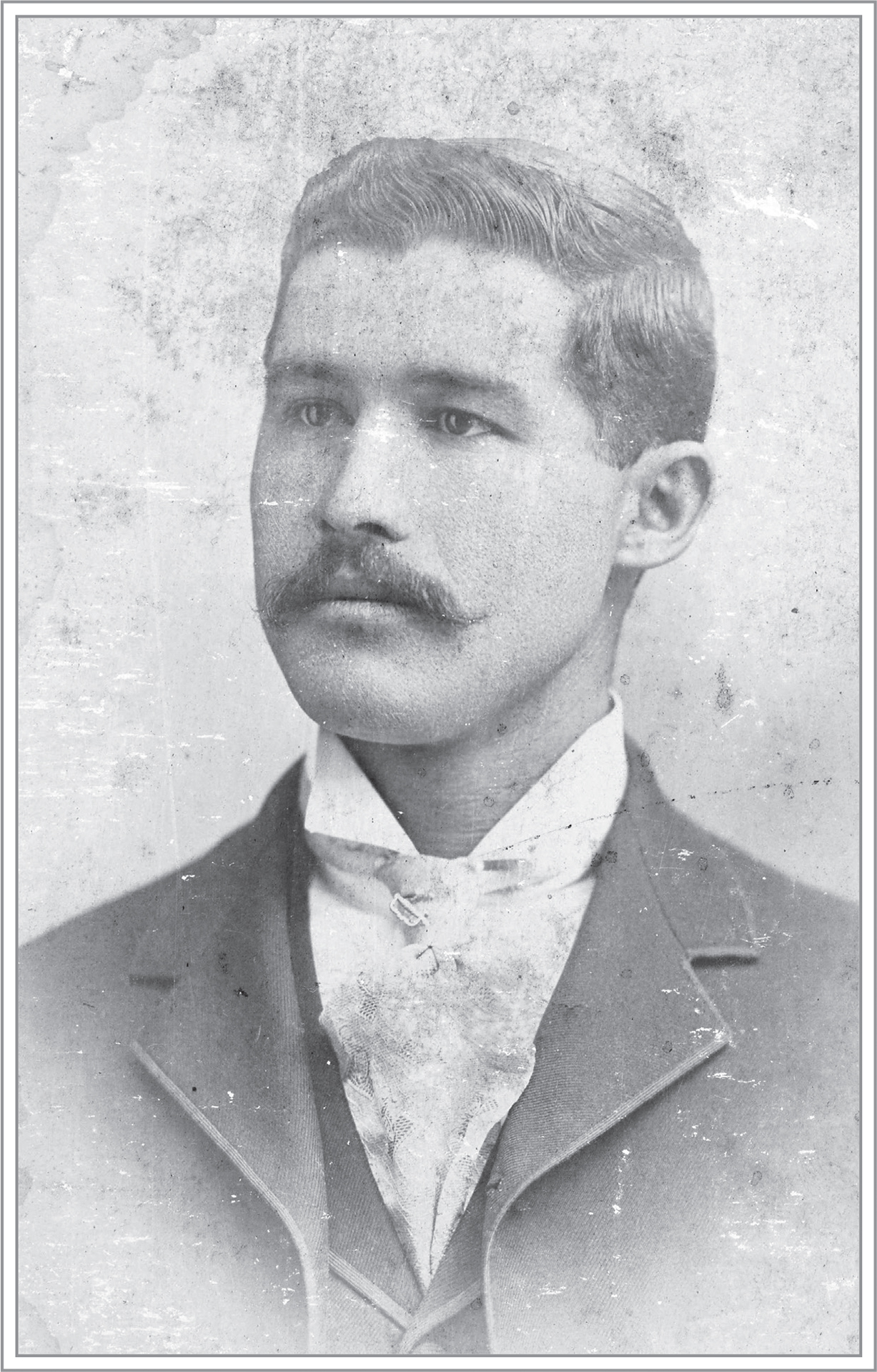

Alex Manly.

B Y A UGUST 1898 , A LEX M ANLY , a thin and handsome man, only thirty-two years old, had made himself into a remarkable American success story. He was a respected community leader in Wilmington, North Carolina; owned and edited the Daily Record , the citys most widely read newspaper; served as the deputy register of deeds; and taught Sunday school at the Chestnut Street Presbyterian Church. And, although he was the grandson of Charles Manly, a former governor of North Carolina, Manlys achievements were in no way a result of family connections.

That was because his grandmother Corinne had been one of Charles Manlys slaves.

Although he was light-skinned, with features that could easily be taken for white, Alex Manly never forgot his African American identity. In fact, the Daily Record was billed as The Only Negro Daily Paper in the World. What made Manlys achievements more unusual was that, by 1898, virtually all of the gains made by African Americans in the 1870s, during Reconstruction, had been swept away by the white supremacists who had once again taken control of state governments across the South. American citizens who happened to be African American were often treated little better than when they had been slaves. Many could not work where they chose or live where they chose; they were often brutalized by whites, arrested under the flimsiest of excuses, and subjected to beatings, rape, and even murder with little or no protection from the local police or courts. In fact, it was not unusual for the local police to be among the worst offenders. And despite anything the United States Constitution may have promised, fewer and fewer African Americans in the South were still able to vote.

But Wilmington, then North Carolinas largest city, was an exception, a thriving port on the Atlantic coast that was also an outpost of racial harmony. More than eleven thousand of its twenty thousand residents were African Americanformer slaves or their descendantsand black men owned a variety of businesses frequented by members of both races, from jewelry stores to real estate agencies to restaurants to barber shops. Although the mayor and city council remained almost entirely white, there were black police officers and firemen.

Members of both races voted regularly and without intimidation. African Americans voted Republican, then the party of equal rights, and exerted a good deal of influence in Wilmington. Democrats, however, the party of white supremacy, had for decades controlled the state house in Raleigh. But in 1894, North Carolinas Populist Party, a group of mostly small farmers, almost all of whom were white, had tired of the Democratic ruling elite and joined with black Republicans to force Democrats from state government.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «Stolen Justice: The Struggle for African American Voting Rights»

Look at similar books to Stolen Justice: The Struggle for African American Voting Rights. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book Stolen Justice: The Struggle for African American Voting Rights and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.