Advance praise for

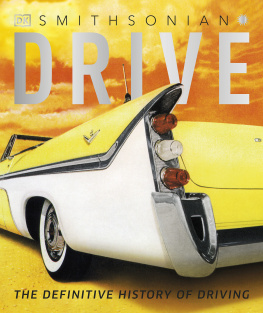

DRIVE!

In suitably fast-paced prose, Goldstone tells the enthralling story of the fraught early days of the Horseless Age. The cast in the high-stakes battle includes brilliant engineers, Gilded Age tycoons, and reckless daredevils both on the track and in the boardrooma heady mix of motors, money, and testosterone. Silicon Valleys billionaires have nothing on these guys for either ingenuity or ruthlessness.

R OSS K ING , author of Brunelleschis Dome

Drive! is an exquisite treasure. Titanic court battles; personal feuds among robber barons; hair-raising, death-defying early automobile races; and a slice of history, beautifully researched and written, that shaped the country in the early twentieth centurythere is something in this book for all lovers of epic, transformative struggles.

D ALE O ESTERLE , Reese Chair, Moritz College of Law, Ohio State University

A wonderful, story-filled saga of the early days of the auto ageWhile aspects of Goldstones book will be familiar to auto buffs, the story is so compelling and well-crafted that most readers will be swept up in his vivid re-creation of a bygone era. The book abounds with detailed accounts of races, auto shows, and heroic cross-country journeys and explains in plain English the advances in automotive engineering that transformed early vehicles from playthings of the wealthy to functional, low-cost cars for the masses. Horse Is Doomed, read one headline in 1895. This highly readable popular history tells why.

Kirkus Reviews (starred)

Copyright 2016 by Lawrence Goldstone

All rights reserved.

Published in the United States by Ballantine Books, an imprint of Random House, a division of Penguin Random House LLC, New York.

B ALLANTINE and the H OUSE colophon are registered trademarks of Penguin Random House LLC.

All photos courtesy of the Library of Congress unless otherwise indicated.

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGING-IN-PUBLICATION DATA

Names: Goldstone, Lawrence, author.

Title: Drive! : Henry Ford, George Selden, and the race to invent the auto age / Lawrence Goldstone.

Description: First edition. | New York : Ballantine Books, 2016. | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2016002581 (print) | LCCN 2016010457 (ebook) | ISBN 9780553394184 (hardback) | ISBN 9780553394191 (ebook)

Subjects: LCSH: AutomobilesHistory. | Automobile industry and tradeHistory. | AutomobilesDesign and constructionHistory. | Automobile drivingHistory. | Transportation, AutomotiveHistory. | BISAC: HISTORY / United States / 20th Century. | TRANSPORTATION / Automotive / History. | BIOGRAPHY & AUTOBIOGRAPHY / Science & Technology.

Classification: LCC TL15 .G645 2016 (print) | LCC TL15 (ebook) | DDC 338.4/762922209041dc23

LC record available at http://lccn.loc.gov/2016002581

ebook ISBN9780553394191

randomhousebooks.com

Book design by Christopher M. Zucker, adapted for ebook

Cover design: David G. Stevenson

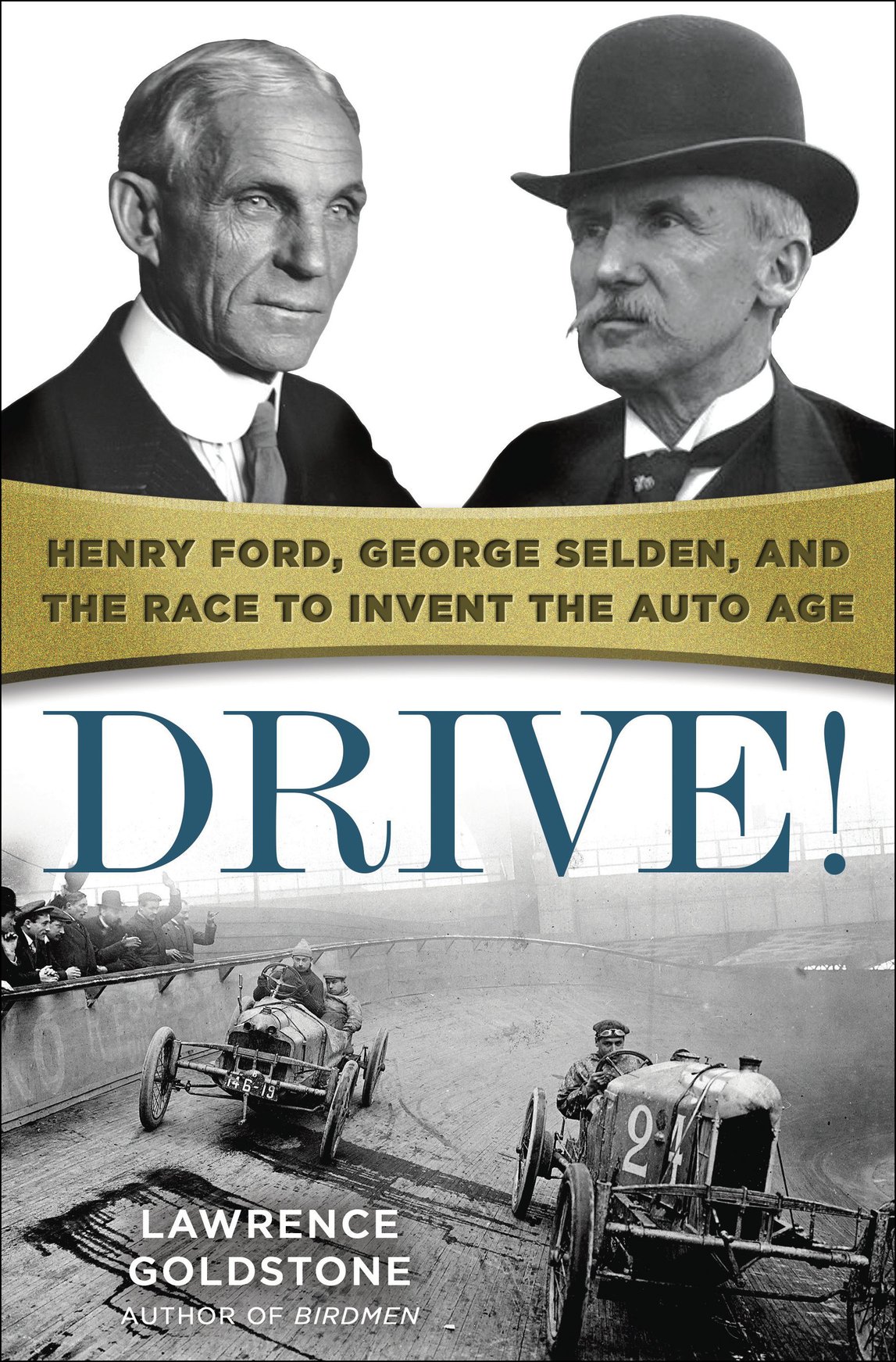

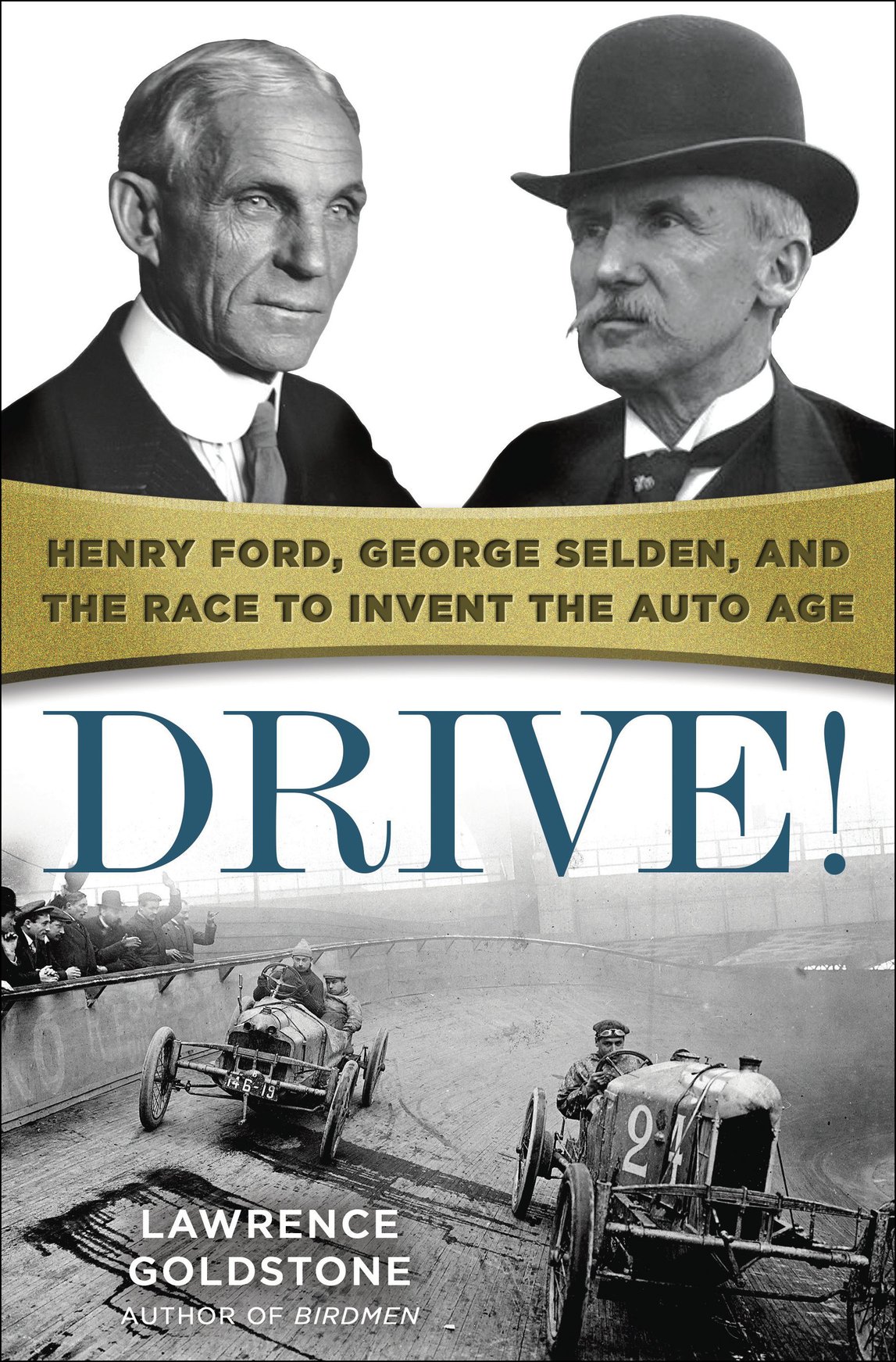

Cover photographs: Henry Ford, courtesy of The Henry Ford; George Selden PhotoQuest/Getty Images; velodrome photos by Maurice-Louis Branger Roger-Viollet/The Image Works

v4.1

ep

Contents

PROLOGUE

O n November 30, 1900, a ruling was handed down in United States district court in Buffalo, New York, that seemed certain to alter the landscape of America, both literally and figuratively. It would propel a few to wealth rivaling that of the Vanderbilts, Astors, and Belmonts and perhaps even approaching the Croesian heights of Pierpont Morgan himself. But for the majority of Americans, the decision foretold higher prices for a potentially inferior version of an item soon to become a necessity.

On that day, Judge John R. Hazel affirmed that, according to a patent granted in 1895, the gasoline-powered automobile had been invented by one and only one man, George Baldwin Selden of Rochester, New York. As a result, each and every gasoline vehicle produced in the United States could be sold only with the permission of the inventor and must include tribute in the form of licensing fees, the amount to be determined by the patents owners.

Any edict of this magnitude was bound to generate controversy, as Hazels did, but this decision featured a particular oddity that made the ruling positively bizarre: George Selden had never and would never attempt to build any form of the device he had claimed as his exclusive property.

The lack of an actual product, however, promised to have as little impact on George Seldens bank balance as it had on his lawsuit. In an era when monopoly interests were defended by the courts and venerated by large segments of the ruling elite, the granting of sweeping licenses on minimal evidence of utility was not considered outlandish. The beleaguered patent office, drowning in applications both serious and frivolous, had become little more than a way station on the road to riches. For the next eleven years, George Selden and the savvy financiers who had hitched their wagons to his paper star collected fees from virtually every major manufacturer of motorcars in the United States. Many of the companies who had been on the wrong side of Judge Hazels decision soon banded together to form a sort of sub-monopoly, funneling fees to the Selden cabal while they extracted even larger fees from their customers. And so might it have continued, except for the energy, conviction, and out-and-out stubbornness of one man, a prototypical revolutionary, seething with contempt for an established order that had rejected him and willing to take any risk to wrench away its power.

In an irony that only two decades hence would elicit wonderor guffawsthat man was Henry Ford.

Ford, who would come to epitomize the very interests that he fought with ferocity in the Selden case, was, as his decade-long war of attrition began, a maverick with a dreamto bring the motorcar, then largely a plaything of the wealthy, to the villages and farms of America.

Many Americans believe that Henry Ford invented the modern automobile, or at least the assembly line and mass production. He did neither. In fact, there is no significant invention in automotive technology for which Ford could personally take credit. Nor was he the first man to consider the egalitarian possibilities of automobile marketing. Fords geniuslike that of Steve Jobs a century laterwas in his ability to improve and to adapt to the demands of the marketplace virtually any process or component with which he came in contact. To produce an automobile within the financial reach of the common man meant it had to be cheaper, lighter, and more reliable, so that was what Ford set his mind and his prodigious energies to create. Then, since the common man needs to be informed of the newest miracles of which he can avail himself, Ford, again like Jobs, also had both the ear and the flair for controlled overstatement that characterize the consummate salesman. That he projected cold sobriety in his public pronouncements made Fords self-promoting homilies that much more credible. Henry Ford might not have been the brilliant inventor of legend, but he was a man whose skills were the perfect match for his ambition.