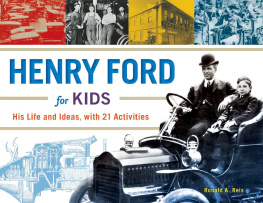

HENRY FORD, A LIFE

In the storybooks, Henry Fords fate was set in motion one day in the summer of 1876, when the thirteen-year-old was riding in a wagon with his father near Detroit. They came upon an enormous road roller - steam-powered, self-propelled, glittering with brass, and clanking mightily. As he was to write forty-seven years later, I can remember that engine as though I had seen it only yesterday... I was off the wagon and talking to the engineer before my father knew what I was up to. That moment gave us the assembly line, the automotive society, suburbia, the shopping mall, and children bickering in the back seat - in short, the world as we know it.

Actually, that account isnt far off the mark. Never mind that thousands of other boys saw similar machines without triggering epiphanies. Never mind Fords demons, his sanctimonious certainty, and the fact that he wasnt an exceptionally good long-term strategist. He was unique, a genius.

Ford was perfectly tuned to his time. While other automakers were turning out expensive toys for rich men, he made sturdy, practical cars that everyone could afford and everyone could drive. His moving assembly line slashed the cost of production. His network of franchised dealers nurtured car ownership and promoted gas stations and better roads. As well see, when his time passed him by, he couldnt adapt to the new world he himself had made. In the end, Henry Ford remains a titan.

Down On the Farm, Up On the Automobile

Henry Ford was born on July 30, 1863, less than a month after Gettysburg, the bloodiest battle of the American Civil War - a time inconceivably remote to us today. He was the first of six children of a prosperous farmer in Greenfield Township, near Dearborn, eight miles from the burgeoning city of Detroit. Declared a state in 1837, Michigan remained a backwater, and the Ford family hacked out a living cutting trees, farming, and fishing.

Henrys first memory was of his father showing him a birds nest. At the age of seven, Ford strode off to a one-room schoolhouse to begin his education. Thanks to his mother and a McGuffey reader, he knew his alphabet and could read somewhat. But school occupied only his winters and the rainy seasons; planting and harvesting dominated the rest of the year.

At the Scotch Settlement School, Henry shared a desk with Edsel Ruddiman, and the two became fast - and, it turned out, life-long - friends. Henry would even name his only son after Ruddiman.

The primary influence in Henrys life, though, was not his friends but his mother. She promoted the virtue of hard work. Life will give you many unpleasant tasks to do, she told him. Your duty will be hard and disagreeable and painful to you at times, but you must do it.

From early childhood, Henry showed an affinity for machinery and a disdain for farm chores. He aint much of a farmer, his father, William, often remarked. He is more of a tinkerer. His sister Margaret recalled her older brothers refusal to do his chores:... that little devil was the laziest bugger on the face of the earth!... Henry would work along all right until ten oclock in the morning, and then he would want a drink of water, but he would never come back!

Henrys avoidance of work had its root in his mothers doctrine of labor that led to results. Hard work meant nothing, she counseled, if it accomplished nothing. Henry wanted things done with the least loss of time and energy, his sister Margaret recalled. If a job could be done more simply, that was the way it should be done. The farm gates were hard to open and close, so Henry made hinges for these gates and a mechanism for opening them and closing them without getting off the wagon.

At the age of twelve, just four months before his fateful encounter with the road roller, Henrys world shattered. His mother, pregnant with her seventh child, died. I thought a great wrong had been done to me when my mother was taken, he later wrote. The house was like a watch without a mainspring.

At sixteen, Ford - a born mechanic, as his mother liked to say - trudged off to Detroit to become an apprentice in a machine shop. He was fired after six days - legend has it because he had the temerity to solve a problem his superiors could not.

Fords father found another apprenticeship for him, only to lure him back to the farm with the offer of forty acres of woodlands. Ford soldiered on, taking solace in cutting wood and working on farm machinery. He opened his own sawmill and married Clara Bryant, the daughter of a neighboring farmer. Some of the first lumber he cut, he wrote later, went into a cottage on my new farm, and in it we began our married life. It was tiny - only thirty-one square feet - but to it he added a workshop. There, he began tinkering with gas engines, first with one cylinder, then with two. I read everything I could find, he said, but the greatest knowledge came from the work.

Then, in 1890, he went to work as an engineer and machinist for the Edison Illuminating in Detroit. With the $45 he took home each week, he and Clara rented a house on Bagley Avenue. Behind it, he erected a brick shed where he could work on his engines.

When he became Edisons chief engineer in 1893, he still had time to spare for his avocation. Horseless carriages were part of the engineering zeitgeist by then, though most people were thinking of steam or electric-powered cars. Ford developed and built his own internal-combustion motor. In 1896, he produced what he called his Quadricycle. It was a four-wheeled buggy, steered by a tiller, with two cruising speeds and no reverse. He finished it shortly before 4:00 a.m. one day in June, and it wouldnt fit through the door of his workshop. So he had to knock down part of the wall to drive it out.

Thomas Alva Edison himself gave the contraption his blessing, and Ford was encouraged enough to get backing from a local lumber baron and start a company to produce his automobiles. It failed in short order, and so did a second, but the third - begun with $28,000 of investors money in 1903 - eventually became the Ford Motor Company.

Success was by no means assured. Clear as it was to Henry Ford that the auto was the wave of the future, that prediction seemed dubious at the turn of the twentieth century. As Harvard Business School Professor Richard S. Tedlow points out, the United States had none of the infrastructure needed for an automotive society. There were no filling stations, no network of improved roads, no repair shops, no insurance policies, no traffic lights or rules of the road. Cars didnt have windshield wipers or headlights or even weatherproof bodies. They were expensive and prone to break down, and no bank would lend money to buy one.

Even worse for the future of a mass market, the dynamics of the auto business made for a relentless drive to produce luxury cars. High-end autos were easier to sell to wealthy customers interested in the latest gadgets. They were also easier to make since their high profit margins could pay the skilled craftsmen who were needed to tinker the uneven parts together. The few entrepreneurs who sensed the possibilities for a mass market were frustrated. Alanson P. Brush, for one, sold a car for as little as $500, but it was as unreliable as it was cheap. Ransom E. Olds did better early on with his merry Oldsmobile, but he lost control of his company to financiers who preferred to cater to the high-end market.

Henry Ford faced the same unstoppable force. His principal backers wanted him to build cars they would like to drive, especially his six-cylinder Model K. But Ford turned out to be a surprisingly good corporate infighter, pitting his investors against each other and making and breaking alliances until, by 1907, he had won voting control of his business. He was left with a lifelong distrust of financiers and bankers; thirty years later, he set up a new company with his son Edsel and began to shift Ford company assets to it. That was just a ruse to convince his remaining investors to sell their shares to him, but it worked, and, at his death, Ford stock was all family-owned.