Dedicated to the memory of Private Joseph Thomas Bartlett, 14782, of the 1st Battalion Dorsetshire Regiment, who lost his life on 20 August 1915, a days march from the battlefield of Agincourt

First published 2015

Amberley Publishing

The Hill, Stroud

Gloucestershire, GL5 4EP

www.amberley-books.com

Copyright W. B. Bartlett, 2015

The right of W. B. Bartlett to be identified as the Author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyrights, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

ISBN 9781445639499 (PRINT)

ISBN 9781445639604 (eBOOK)

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without the permission in writing from the Publishers.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

Typesetting and Origination by Amberley Publishing

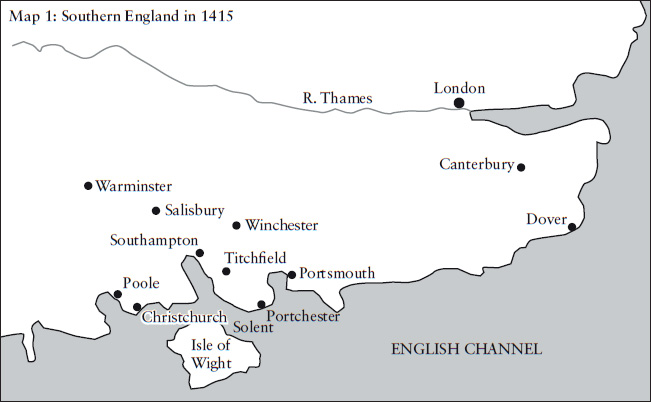

Map redrawing by Thomas Bohm, User Design Illustration

Printed in the UK.

CONTENTS

MAPS

INTRODUCTION

What follows is not so much a history as an interpretation. There are a number of chroniclers who wrote about the Battle of Agincourt both at the time and in the years, decades and centuries that followed. It might be thought that this makes us more certain of our facts, but this is not so. The chroniclers wrote with specific audiences in mind, to make a point either for or against a certain cause, and in the process they were not above making up a fact or two; such at least we can assume from our general knowledge of human nature, not to mention the contradictions that appear in the various accounts.

It is impossible to write the definitive story of the Battle of Agincourt; not only has the story become varnished with layer after layer of myth, but the original sources often contradict each other in key details. As a result, anyone who writes of Agincourt is forced to paint their own personal picture of events. Not everyone will agree with the end result, but this is what makes the study of history interesting.

But there is one thing that nearly all the chroniclers, both English and French, agree about, and that is the remarkable nature of Henry Vs triumph. If there is a consistency to be found among most of the chroniclers it is in the conclusion that the English were significantly outnumbered by their French foe and that their victory represented a triumph over great adversity. This is how the battle has been remembered, partly of course thanks to a truly remarkable Englishman by the name of William Shakespeare.

Much has been done in recent years to interpret the battle properly and some outstanding historical research, in particular by Professor Anne Curry of the University of Southampton, has painstakingly recreated precious information such as the Muster Rolls of all those who embarked for France from England in August 1415. This has enabled others to understand much more about the campaign than would ever have been the case in the past, and all those who wish to understand the Battle of Agincourt are forever in the debt of such experts for their insight and talent as well as their hard work.

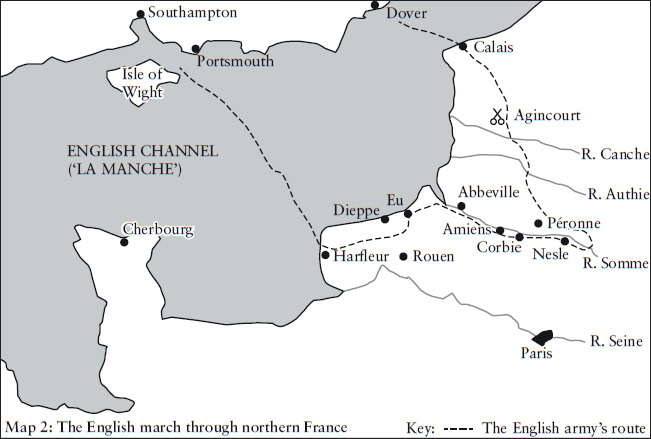

Walking the ground in southern England and north-western France has been a rewarding exercise in itself, and many an interesting site remains from those days. The site of the battlefield still remains atmospheric (if one ignores the painted cardboard figures of archers and knights now present in the hedges that make a slightly surreal impression on modern visitors), informative up to a point and, on a soggy October day, truly muddy.

It is hard, though, to walk the ground in the area of Agincourt, a peaceful farming landscape through which most English visitors rush from the Channel Tunnel at Calais to points further south in France, without being reminded of another, much bloodier battle, or more accurately series of battles, which took place on a world stage almost exactly 500 years later nearby. The example of the later sacrifice of ordinary men and women in the First World War serves as a salutary reminder that war is very rarely glorious, whatever the Shakespeares of this world would have us believe.

Most English families were affected by that later conflict, and mine most certainly was. It was in part as a result of my research for this book that I knelt for the first time by the grave of my great-grandfather Joseph Thomas Bartlett, buried in Dartmoor Cemetery just outside Albert, past which Henry V and his army marched on their way to the field of Agincourt. Private Bartlett lost his life on 20 August 1915, exactly 500 years after Henry V was laying siege to Harfleur. He died during a supposedly quiet time on the front, nearly a year before the famous Battle of the Somme began.

It was a humbling and emotional experience to remember the life of a twenty-nine-year-old from a working-class background who left behind him a widow and several young children, who would later face their own heroic struggle to survive during the terrible years of the Great Depression of the 1930s in particular, a struggle that helped create some of my own familys legends. Their ultimate victory too was, in its own way, a triumph against the odds. I could only find one simple phrase to enter in the visitors book at the cemetery thank you.

Life goes full circle. We will see in what follows that life could be as hard for a war hero in 1415 as it was in 1915, particularly in the remarkable story of Thomas Hostell. Agincourt told different tales for different people. For the king, Henry V, it was the day that shaped his legacy in history. For men-at-arms, such as Edward, Duke of York, it would also be a remarkable occasion. And for English archers such as Thomas Pokkeswell it would be a day that made legends of a class known simply as the English yeoman, to whom the triumph of Agincourt more than any others belongs.

1

PROLOGUE

I am afeard there are few die well that die in a battle.

William Shakespeare, Henry V, Act 4, Scene 1

Henry V, by the Grace of God King of England, Ireland and France. So at least Henry would have it, although there were some even in England who would dispute his right to be king of anywhere at all. But as he looked across the muddy, ordinary field in front of him, even the undemonstrative Henry would have allowed himself to feel a degree of self-satisfaction. For he had just struck a blow (or more to the point his army had) that would surely prove, in this age when might equated to right and the judgement of battle was equivalent to the judgement of God, that there was now no doubting his claim to rule on anyones part.

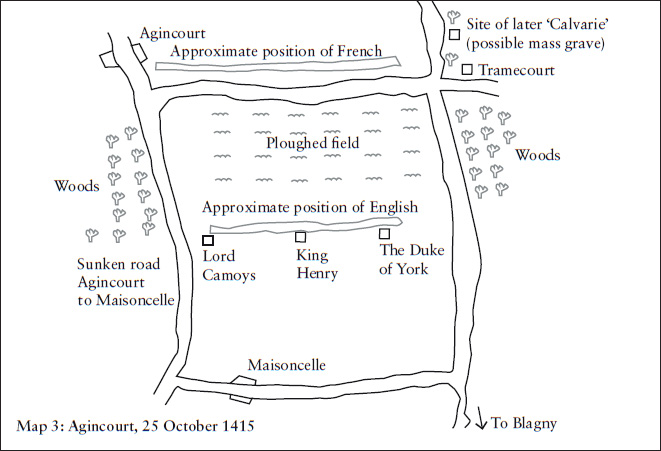

Yet for many round about him there was little to celebrate, for there, thrown up in heaps across the mud-choked ground, were pile after pile of the dead (mainly French but not exclusively so). There they lay; in the main still, bloodied, lifeless, a thick hedge of corpses (though wounded and dying there still were in plenty). As they had breathed out their last, their bodies pierced by arrows or their heads smashed in with poleaxes, they formed as effective a barrier against further French attacks as any wall made of stone would have done. The thousands of French soldiers behind them, whether or not they wished to make their way past them into the killing zone, were unable to do so. The English were protected from further French attacks by the cadavers of those they had already slain.