Historical texts can often reflect the time period that they are written in and new information is constantly being discovered every day. This book was originally published in 1995 and much has changed since then. While every effort has been made to bring this book up to date, it is important to consult multiple sources when doing research.

Copyright 1995 by Jules Archer

Foreword 2015 by Sky Pony Press, an imprint of Skyhorse Publishing, Inc.

First Sky Pony Press Edition 2015

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any manner without the express written consent of the publisher, except in the case of brief excerpts in critical reviews or articles. All inquiries should be addressed to Sky Pony Press, 307 West 36th Street, 11th Floor, New York, NY 10018.

Sky Pony Press books may be purchased in bulk at special discounts for sales promotion, corporate gifts, fund-raising, or educational purposes. Special editions can also be created to specifications. For details, contact the Special Sales Department, Sky Pony Press, 307 West 36th Street, 11th Floor, New York, NY 10018 or .

Sky Pony is a registered trademark of Skyhorse Publishing, Inc., a Delaware corporation.

Visit our website at www.skyponypress.com.

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available on file.

Cover design by Brian Peterson

Cover photo credit: Library of Congress

Print ISBN: 978-1-63220-604-6

Ebook ISBN: 978-1-63220-765-4

Printed in the United States of America

Interior picture credits:

Pictures 1-1, 1-2, 1-3, 1-10, 2-9 and 2-10: National Archives.

Pictures 1-9, 1-11, 2-3, 2-4, 2-6 and 2-7: Library of Congress.

Pictures 1-4, 1-6, 1-12, 2-1 and 2-8: The Bettmann Archives.

Pictures 1-5, 1-8, 2-2, 2-5, 2-11, and 2-12: Illinois State Historical Library.

Picture 1-7: Culver Pictures, Inc.

To my grandchildren,

Zoe Alena and Nikkita Paige Archer,

and Dr. Sue Hand Archer

CONTENTS

FOREWORD

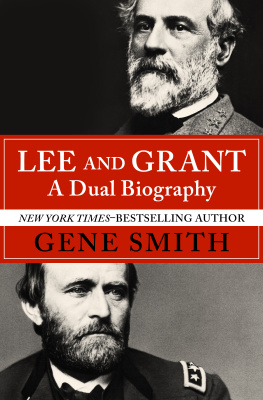

Americans like discussing their heroes in pairs: George Washington and Abraham Lincoln; Babe Ruth and Lou Gehrig; Meriwether Lewis and William Clark; and, of course, Ulysses Simpson Grant and Robert Edward Lee.

Seeing double, as Jules Archer invites us to do for Grant and Lee in A House Divided , gives us an opportunity to look at two individuals and begin to understand how they were unique in their own way. At the same time, it also helps identify the experiences and attitudes they shared. The traits that belong only to one person are probably not going to be the ones that command attention or serve as examples for others. These traits are simply personal peculiarities, not traces of genius. But when two people with very similar traits, habits, or expectations are pitted against each other during trying times, we are most likely looking at the real elements of their greatness.

Ulysses S. Grant and Robert E. Lee came from very different backgrounds. Lee was born in Virginia to a family with four generations of prominent military men; his father was one of George Washingtons favorite lieutenants during the American Revolution. But Lees father, however good a soldier he was, spent away the familys money, home, and reputation, and abandoned them (including Robert). Roberts devotion ran instead toward his mother, Ann Carter Lee, and it was his mothers vast web of relations who put a roof over his head and saw that he was educated.

Grants early life was almost the exact opposite. His mother, Hannah, was distant and uninvolved. It was Grants father, Jesse, who was determined that his son should amount to somethingalthough that something never reached very high. The Grants, unlike the Lees, had no famous ancestors.

Grant and Lee both attended West Point, largely because it offered a free college education in return for service in the United States Army after graduation. But from that point, the lives of the two young men again diverged greatly. Grant hated West Point. His most earnest wish was for Congress to close it down, and he graduated closer to the bottom than to the top of his class. Lee, as Jules Archer shows, was awarded the highest honor of his class and later returned to serve for several years as superintendent in the 1850s.

The two got their first taste of war in the same conflict, the Mexican War of 184648. But once more, the experience sent them in very different directions. Lee was praised and promoted. Grant got much less praise, and was assigned to a miserable post in the Far West, which ultimately drove him to alcoholism. Afterwards, he was forced to resign from the army. Grant then flopped in every business venture he undertook for the next six years.

But the back stories of these men and their past is of very little consequence when compared to the characteristics they shared. These characteristics brought them challenge, fame, and a collision of wills that still marks our nation.

One trait common to both was a deep drive to succeedLee, by duty, and Grant, by a deep streak of unwillingness to admit failure. In 1861, as the nation was being torn in two by secession and civil war, Lee was presented with a gift he could only have dreamt-of back in his cadet days at West Point: command of the entire US Army as it moved to subdue the secessionists new Southern Confederacy. Lee had little sympathy with secession, and even less with the secessionists motiveto protect slavery in the Confederate states. But Virginia had chosen to throw its lot with the Confederacy and Lee felt bound by ties of family, of home, and of history to follow his state. He declined the offer, resigned from the US Army, and put himself at the disposal of the Confederate Army instead.

Grant on the other hand, had no conflict over his loyalty to the United States, though he did have difficulty persuading people to forget his record of failure and alcoholism. But at the beginning of the Civil War anyone with even a shadow of military experience was needed. Once in command, Grant never looked back. Archer digs into Grants own writings for the words which capture Grants temperament: One of my superstitions had always been when I started to go anywhere, or to do anything, not to turn back, or stop until the thing intended was accomplished. Beginning with his capture of the twin Confederate outposts, Fort Henry and Fort Donelson, in February of 1862, Grant was described by one officer as a man who dismisses all possibility of defeat.... If his plans go wrong he is never disconcerted but promptly devises a new one and is sure to win in the end.

Another characteristic which Grant and Lee shared was a clear understanding of what their duty would cost others. Neither enjoyed war for wars sake. Archer reminds us that Grant had all the instincts of a pacifist and that Lee wrote a letter to his wife early in the war, wishing he could retire to private life, so that I could be with you and the children. But Lee knew that unless the Confederacy was willing to expend every effort, and quickly, it would inevitably lose. Grant, likewise, understood that victory in the war would never be complete until slavery had been torn up by the roots. There had to be an end of slavery, Grant said years later. No convention, no treaty was possibleonly destruction. In the end, both were right. The Confederacy failed to make the effort Lee called for and it was crushed. And Grant refused to consider any form of peace short of unconditional surrender.