Copyright 2013 by The University Press of Kentucky

Scholarly publisher for the Commonwealth,

serving Bellarmine University, Berea College, Centre College of Kentucky, Eastern Kentucky University, The Filson Historical Society, Georgetown College, Kentucky Historical Society, Kentucky State University, Morehead State University, Murray State University, Northern Kentucky University, Transylvania University, University of Kentucky, University of Louisville, and Western Kentucky University.

All rights reserved.

Editorial and Sales Offices: The University Press of Kentucky

663 South Limestone Street, Lexington, Kentucky 40508-4008

www.kentuckypress.com

17 16 15 14 13 5 4 3 2 1

Maps by Dick Gilbreath, University of Kentucky Cartography Lab.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

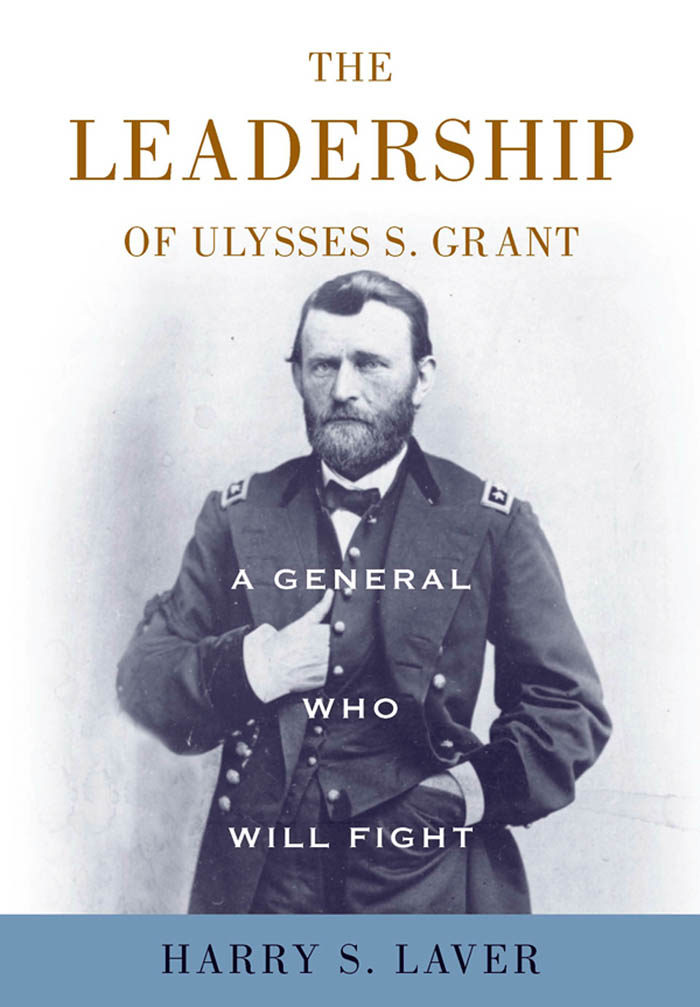

Laver, Harry S.

A general who will fight : the leadership of Ulysses S. Grant / Harry S.

Laver.

pages cm

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-0-8131-3677-6 (hardcover : alk. paper)

ISBN 978-0-8131-3678-3 (pdf)

ISBN 978-0-8131-4075-9 (epub)

1. Grant, Ulysses S. (Ulysses Simpson), 1822-1885Military leadership.

2. United StatesHistoryCivil War, 1861-1865Campaigns.

3. Command of troopsCase studies. I. Title.

E672.L38 2012

This book is printed on acid-free paper meeting the requirements of the

American National Standard for Permanence in Paper for Printed Library

Materials.

Manufactured in the United States of America.

| Member of the Association of

American University Presses |

I have pursued mine enemies, and overtaken them:

neither did I turn again till they were consumed.

I have wounded them that they were not able to rise:

they are fallen under my feet.

For thou hast girded me with strength unto the battle.

Psalm 18:3739

Well Grant, weve had the devils own day, havent we?

Yes, lick em tomorrow though.

April 6, 1862

Introduction

A Great Force of Will

The Commander must have a great force of will.

Carl von Clausewitz

Sunday, April 6, 1862, dawned quietly as Ulysses S. Grant sat down at the breakfast table of the Cherry mansion in Savannah, Tennessee. Shuffling through a stack of mail on the table, he leaned forward to take the first sip of coffee when up the Tennessee River valley came the rumbling of artillery fire. With the cup poised at his lips, he paused, listened for a moment, then returned the coffee to the table and announced to his staff, Gentlemen, the ball is in motion. Lets be off. Making their way out the front door and down stone steps crafted years ago by slaves, he and his staff were soon on board the Tigress, whose crew was frantically working to get up a head of steam for the nine-mile trip south to Pittsburg Landing. There, an army of Federal soldiers was camped near a small log Methodist church known locally as the Shiloh Meeting House. Inexplicably, Grant had established his headquarters at distant Savannah on the opposite, eastern side of the river, and, while he spent most of each day with his army, this Sunday morning the Confederates had caught him as unaware as a sleeping sentry.

For the men of Grants command, the day had begun with the drowsy routine of a Sunday morning. As the first streaks of light ribboned from the eastern sky, nearly forty thousand Union soldiersand calling them soldiers at this point of the war required a bit of imaginationawakened to the clank of pots and pans, the scent of wood smoke and bacon. Mostly farm boys from Iowa, Indiana, Illinois, Ohio, and other midwestern states, this was a green army; some had signed up in January or February, others only a few days ago. The newer regiments had just received their muskets and had yet to master the manual of arms, the precise choreography of loading and firing the weapon. A smattering knew how to march in column and form a line of battle; fewer could maneuver as a unit on the field, even without the unnerving hiss of bullets and shrapnel. The men of Maj. Gen. John McClernands First Division were the veterans, survivors of the action two months earlier at Forts Henry and Donelson. There, they had caught a glimpse of the mysterious Rebels, delivered their first volley and received the same, and in the process won the first Union victories of the war. But they were the exception; most of the men at Shiloh had not seen the elephant, and so, despite an abundance of bravado and unearned confidence, they were an army of little training and even less experience, not knowing enough to be wary or watchful. The failure to keep good guard was a shortcoming, not just of these green soldiers and their company captains, but of their senior officers as well, including the army commander, Grant. Now, like most mornings, breakfast campfires drew the men together in small circles, where they contemplated another day of close-order drill and the likely annoyance of a late afternoon rain.

The pop and crackle of desultory musket fire coming from the south was the first indication that something was amiss. Roughly a mile and a half from Shiloh Church, where Fifth Division commander Brig. Gen. William T. Sherman had established his headquarters, Maj. Aaron B. Hardcastles Third Battalion of Mississippians had attacked. The vanguard of Gen. Albert Sidney Johnstons forty-thousand- strong Army of the Mississippi, Hardcastles Rebels were driving Union pickets back through forty-acre Fraley field. From across the South, Johnston had gathered this host of Confederates in Corinth, Mississippi, twenty-two miles southwest of Pittsburg Landing. Considered by Jefferson Davis to be the Souths best field commander, Johnston had set his army in motion three days earlier with the objective of striking a fatal blow to Grants invaders before Don Carlos Buells Army of the Ohio, moving south from Nashville, could reinforce. Brushing aside the concerns of Gen. P. G. T. Beauregard, the

When around nine oclock Grant disembarked from the Tigress at Pittsburg Landing, he found along the riverbank a roiling mass of men who had fled the fighting, panicked horses straining in their harnesses, and officers shouting with equal futility at both. He ordered more ammunition to the front; then, although still on crutches because of a sprained ankle, he mounted with assistance and made his way forward in search of the fight. On the Union right flank, Sherman and his Fifth Division had put up a stout defense at Shiloh Church before falling back to Jones field, less than a mile from the landing, and that is where Grant found him around ten oclock. A bloody bandage bound up Shermans right hand, which throbbed from a wound suffered earlier in the day. It might well have been much worse; seconds before Sherman was hit, an aide, Priv. Thomas Holliday of Illinois, took a bullet to the head, spattering brain and blood across Shermans face and uniform. Nevertheless, there was fire in his eye, and, seeing that Sherman was doing all he could with what he had, Grant moved to the left to visit his other division commanders. At the center of the battle line, he came on Benjamin Prentiss, the forty-two-year-old Illinois politician who now wore the stars of a brigadier general. Prentiss, whose Sixth Division had absorbed the first Confederate blows in Fraley field, had collected the remnants of his command and spread them out along an old wagon trace that ran perpendicular to the Confederates line of advance. After assessing the situation, Grant gave orders to Prentiss that were as grim as they were concise: hold your position at all hazards. Wheeling his horse around, he headed back north, looking to cobble together a