Table of Contents

This book is dedicated to my loving wife,

Susan Weidemoyer Bonekemper;

my ever-supportive parents,

the late Edward H. Bonekemper II and Marie H. Bonekemper;

my inspirational Muhlenberg College history professor,

Dr. Edwin R. Baldrige;

and my departed British/Bermudian Civil War

connoisseur and friend, John W. Faram.

INTRODUCTION

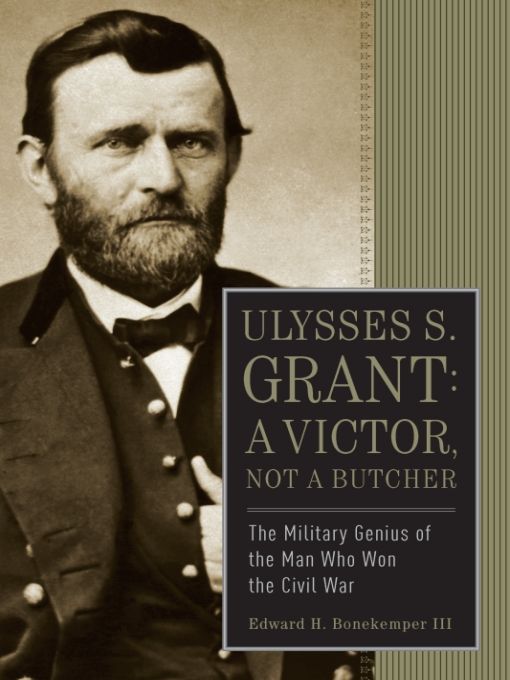

Many casual readers of Civil War history come to the conclusion that Robert E. Lee wrought miracles with an outnumbered army and that, by contrast, Ulysses S. Grant was a butcher who slaughtered his own men and won solely by brute force and sheer numbers. Over decades of reading about the Civil War, I have come to contrary conclusions about both men.

Discussions about Robert E. Lee with my late father-in-law, Alfred W. Weidemoyer, led to our concluding that Lee had escaped blame for his many failures during the war and to my writing How Robert E. Lee Lost the Civil War. A brilliant and well-read friends insistence that Grant was a butcher has encouraged me to write this book. As I wrote this book, my continuing research only deepened my conviction that Grant was a great general whose reputation was besmirched by early Civil War historians who had motives of their own and that his generalship has never received the credit it deserves for winning the Civil War.

In these pages, I attempt to summarize Grants Civil War battles and campaigns with a particular focus on whether his casualties reflected butcher-like conduct. I conclude that he conquered the western third of the Confederacy with a minimum of casualties, drove a stake into the middle of the Confederacy with minimal losses again, and then came east to win the war with tolerable casualties in less than a year. Far from being a butcher, Grant relied on maneuver, speed, imagination, and persistencein addition to forceto win the Civil War.

In addition to my narrative and arguments, I have included three appendices that support my position. Appendix I contains a summary of historians treatment of Grantfrom the Lost Cause historians of the early post-war period to those who have reconsidered and revived his record. Appendix II contains a comprehensive summary of various parties estimates of the casualties that both sides suffered in the battles and campaigns in which Grant was involved; it provides casualty estimates drawn from a variety of Civil War books, articles, and documents. Finally, Appendix III discusses the surprising closeness of the presidential election of 1864, an election that affected Grants approach to battle in 1864 and the outcome of which was affected by Grants aggressive nationwide campaign of that year.

Preface

THE GREATEST CIVIL WAR GENERAL

Why has Grant so often been labeled a butcher and Robert E. Lee a hero? Accusations that Grant was butchering his own soldiers first began during the warparticularly during his aggressive 1864 campaign against Lee to secure final victory for the Union. During that campaign (the Richmond or Overland Campaign), Mary Todd Lincoln said, [Grant] is a butcher and is not fit to be at the head of an army. On June 4, 1864, Union Secretary of the Navy Gideon Welles wrote in his diary, Still there is heavy loss, but we are becoming accustomed to the sacrifice. Grant has not great regard for human life. One Southerner said at the time, We have met a man this time, who either does not know when he is whipped, or who cares not if he loses his whole army.

The butcher accusations continued in the early post-war period. As early as 1866, a southern writer, Edward Pollard, referred to the match of brute force to explain Grants victory over Lee. Even northern historians criticized Grant. In 1866, New York Times war correspondent William Swinton wrote in his Campaigns of the Army of the Potomac that Grant relied exclusively on the application of brute masses, in rapid and remorseless blows. John C. Ropes told the Military Historical Society of Massachusetts that Grant suffered from a burning, persistent desire to fight, to attack, in season and out of season, against entrenchments, natural obstacles, what not.

Beginning in the 1870s, former Confederate officers played a prominent role in criticizing Grantespecially in comparison to Lee. Lieutenant General Jubal A. Early, in an 1872 speech on Lees birthday, said, Shall I compare General Lee to his successful antagonist? As well compare the great pyramid which rears its majestic proportions in the Valley of the Nile, to a pygmy perched on Mount Atlas. In the 1880s, Lieutenant General Evander M. Law wrote, What a part at least of his own men thought about General Grants methods was shown by the fact that many of the prisoners taken during the [Overland] campaign complained bitterly of the useless butchery to which they were subjected....

Likewise, Lees former adjutant, Walter H. Taylor, elevated Lee at Grants expense in General Lee: His Campaigns in Virginia 1861-1865 with Personal Reminiscences, which was published in 1906. Of the Overland Campaign, Taylor said: It is well to bear in mind the great inequality between the two contending armies, in order that one may have a proper appreciation of the difficulties which beset General Lee in the task of thwarting the designs of so formidable an adversary, and realize the extent to which his brilliant genius made amends for the paucity of numbers, and proved more than a match for brute force, as illustrated in the hammering policy of General Grant. Taylor also claimed that [Grant] ... put a lower estimate upon the value of human life than any of his predecessors....

Sometimes the accusation has been more subtle, as in Robert D. Meades 1943 book on Judah Benjamin: In the spring of 1864 Grant took personal command of the Union Army in Virginia and, with a heavily superior force, began his bludgeoning assaults on Lees weakened but grimly determined troops. A 1953 dust jacket on a Bruce Catton book said (contrary to Cattons own views): [The Army of the Potomacs] leader was General Ulysses S. Grant, a seedy little man who instilled no enthusiasm in his followers and little respect in his enemies. In 1965, pro-Lee historian Clifford Dowdey said of Grant: Absorbing appalling casualties, he threw his men in wastefully as if their weight was certain to overrun any Confederates in their path. In terms of generalship, the new man gave Lee nothing to fear, and described Grant as an opponent who took no count of his losses. A 1993 article in Blue & Gray Magazine referred to the butchers bill of the first two weeks of the Overland Campaign.

Historian Gregory Mertz said it well:

Grant enjoyed little of the glory for his contributions to the [Army of the Potomacs] ultimate success, and was the recipient of much of the blame for the disasters. Despite moving continually forward from the Wilderness to Petersburg and Richmond, ultimately to Appomattox, and executing the campaign that ended the war in the East, Grant has received little credit, and is most remembered for the heavy losses of Cold Harbor, which tagged him with the reputation of a butcher.

Even today, examples abound. In 2001, a reporter wrote: Despite occasional flashes of brilliant strategy and admirable persistence, Grant still comes off looking like a butcher in those final months. Another reporter, writing in 2002 and regarding him as an intellectual lightweight, referred to last-in-class types, such as Ulysses S. Grant.