I n the year 1000, England had been a united kingdom for less than a century. In 927, Athelstan king of Wessex and Mercia, the grandson of Alfred the Great, had conquered Northumbria, so extinguishing the last segment of independent Scandinavian rule. There had been periods after this when more than one king ruled in England, but they had not lasted long. By the turn of the millennium, the latest king of the Wessex line, Ethelred the Unready, was engaged in endless campaigning and diplomacy to preserve the frontiers of that kingdom and extend his influence over his neighbours. To the west lay the politically fragmented country of Wales, the border with which had been defined by the eighth-century linear earthwork Offas Dyke from Basingwerk on the Dee to a point just east of the Wye estuary.

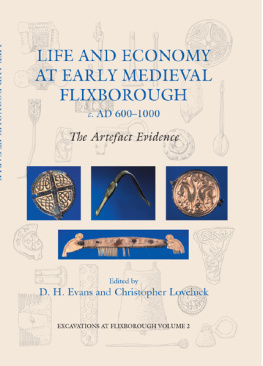

England in 1000 was a country whose population had been growing steadily for several centuries but may still have been some way short of the level reached in Roman times. Only one person in ten lived in towns and there was a heavy preponderance towards the east and south of the country. Among the iconic structures associated with the medieval English landscape, castles had not yet arrived and monasteries were relatively few in number although those which existed were exceptionally well-endowed, some with incomes which Domesday Book would later show to be comparable to the riches enjoyed by leading favourites of William the Conqueror. Parish churches were, as yet, mostly small and timber-built but they were certainly proliferating, and those serving rural settlements were often witness to an important process of transition, as nucleated villages and open arable fields farmed in common were coming to replace dispersed hamlets with individually farmed enclosed fields: but this was a phenomenon which had neither run its full course by 1000, nor would ever characterize large parts of England.

If the year 1000 can be taken for convenience as a starting point for the period covered by this book, 1540 may fairly be treated as its end. All periodization is of course open to challenge,

The political history of the intervening five centuries had revolved around two principal issues: first, the relationship between England and her neighbours, to north, west and south east, and second the extent to which power over the kingdom as a whole should be shared between the monarch and some form of representative assembly. One potential issue which never became the force it might have done was the identity of England and the English. The divisive legacy of 1066 that of a Norman/French lite ruling over the subjugated English masses eventually disappeared in the thirteenth century, following the loss of Normandy to France in 1204 and the triumph of the English language as the mother tongue even of the aristocracy. As late as 1405, three rebels against Henry IV optimistically partitioned England and Wales between them in a Tripartite Indenture. But these turned out to be fleeting affairs. Essentially, England retained its political cohesion throughout the period troops and taxes could be raised in the south to assist in the defence of the north despite there being some local adjustments to the frontiers from time to time and notwithstanding the existence of a few regions, notably Cheshire and Durham for much of the period, where the normal processes of royal government were modified so as to respect the privileges of a local potentate. Although the landscape of England was infinitely varied, politically the country was unified, in a way that medieval France, Germany, Spain and Italy were not. Local and regional affinities were certainly strong in medieval England, but there was general acceptance that these belonged within the context of one overarching kingdom. For the development of the English landscape, all this mattered. The kings journeys, the intermarriages between noble families, the selection of clergy for senior posts: all were conducted on a country-wide basis, contributing to a network of shared information about farming practices, building styles and skilled personnel across the country as a whole. Regional variations abounded, as anyone who crosses the country today through different terrain and geology can readily perceive, but so did connections between landscapes created in different parts of the kingdom.

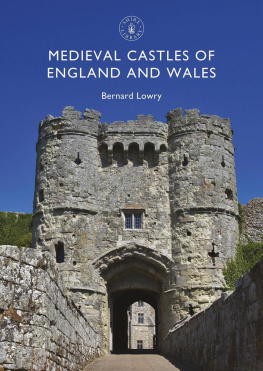

But if England was formally united, it was hardly ever politically isolated. For most of the reign of Cnut (101635), the kingdom was part of a Scandinavian empire embracing Denmark and Norway. Had Cnuts dynasty become established long-term, these Scandinavian links might have significantly shaped Englands political and cultural development, with manifestations in architecture, for example, which had more in common with Norway than with France. In the event, his line died out in 1042 and the next conqueror, William duke of Normandy, ruled kingdom and duchy together and went on to establish overlordship of Scotland and Wales. Through many vicissitudes, a political attachment to territory in France was to persist until Calais was eventually lost in 1558. Within the British Isles, Lordship of Ireland was added by Henry II in the 1170s, and although most of the country beyond what came to be known as the Pale (the area around the east coast ports) was subsequently left to its own devices, Wales and Scotland demanded more sustained attention; their bequests to the landscape include the fine series of castles built to secure Edward Is conquest of North Wales and the fortified pele towers which arose in the vulnerable northern shires after the Scots success at Bannockburn in 1314. Eventually, Wales would provide the base from which Henry VII launched his successful bid for the throne in 1485, the prelude to his sons Act of Union. In turn, a decisive English victory over the Scots at Flodden in 1513 would bring some peace for a generation, and a series of dynastic manoeuvres would unite the crowns of Scotland and England in the person of James VI and I in 1603.

The conduct of war and the question of how it should be paid for were issues which obliged medieval kings regularly to consult their subjects. The emergence of representative assemblies of the community of England can be traced to a period well before

An unfolding political narrative, dominated by Englands relations with her neighbours and by successive kings dealings with lords and commons, But they recur time and again, and it is appropriate here to give brief consideration to each of them in turn.

There is broad though not complete agreement among scholars over the trends in medieval population, but considerable disagreement over what the size of that population might have been. Archaeological evidence suggests that by the seventh century the population had begun to recover from a prolonged decline in the late-Roman and immediate post-Roman

Thereafter, estate surveys, rentals and the government enquiry which produced the Hundred Rolls of 1279 all demonstrate a burgeoning population. Cautious estimates of population totals for villages in Cambridgeshire, Essex, Leicestershire and west Yorkshire suggest a population density in 1300 very close to sometimes greater than that which pertained in the rural areas of these shires at the time of the 1801 census. If towns over 5,000 population

The trend of population in the second quarter of the fourteenth century is by no means certain. There is evidence of abandoned land especially in the more arable south and east, to set against a continuing search for new farmland in the more pastoral north and west. This is not of course the same as an improvement in the quality of life: bereavement remained a frequent experience and in many places it became a struggle to keep communal farming going, with too few people to till the land. But there can be no doubt that, in social and economic terms, the Black Death and its immediate aftermath must still be seen as one of the great turning points in English history.