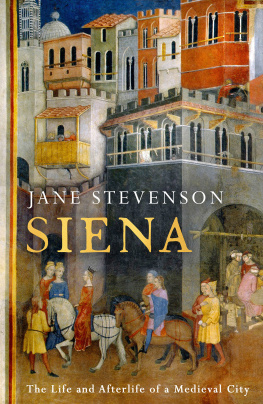

S I E N A

JANE

STEVENSON

S I E N A

The Life & Afterlife

of a Medieval

City

www.headofzeus.com

Bird'seye view plan of Siena by M. Merian, 1638

The rooftops of Siena

Kai Gilger, Wikimedia Commons

First published in the UK in 2022 by Head of Zeus Ltd,

part of Bloomsbury Publishing Plc

Copyright Jane Stevenson, 2022

The moral right of Jane Stevenson to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act of 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of both the copyright owner and the above publisher of this book.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN (HB) 9781801101141

ISBN (E): 9781801101165

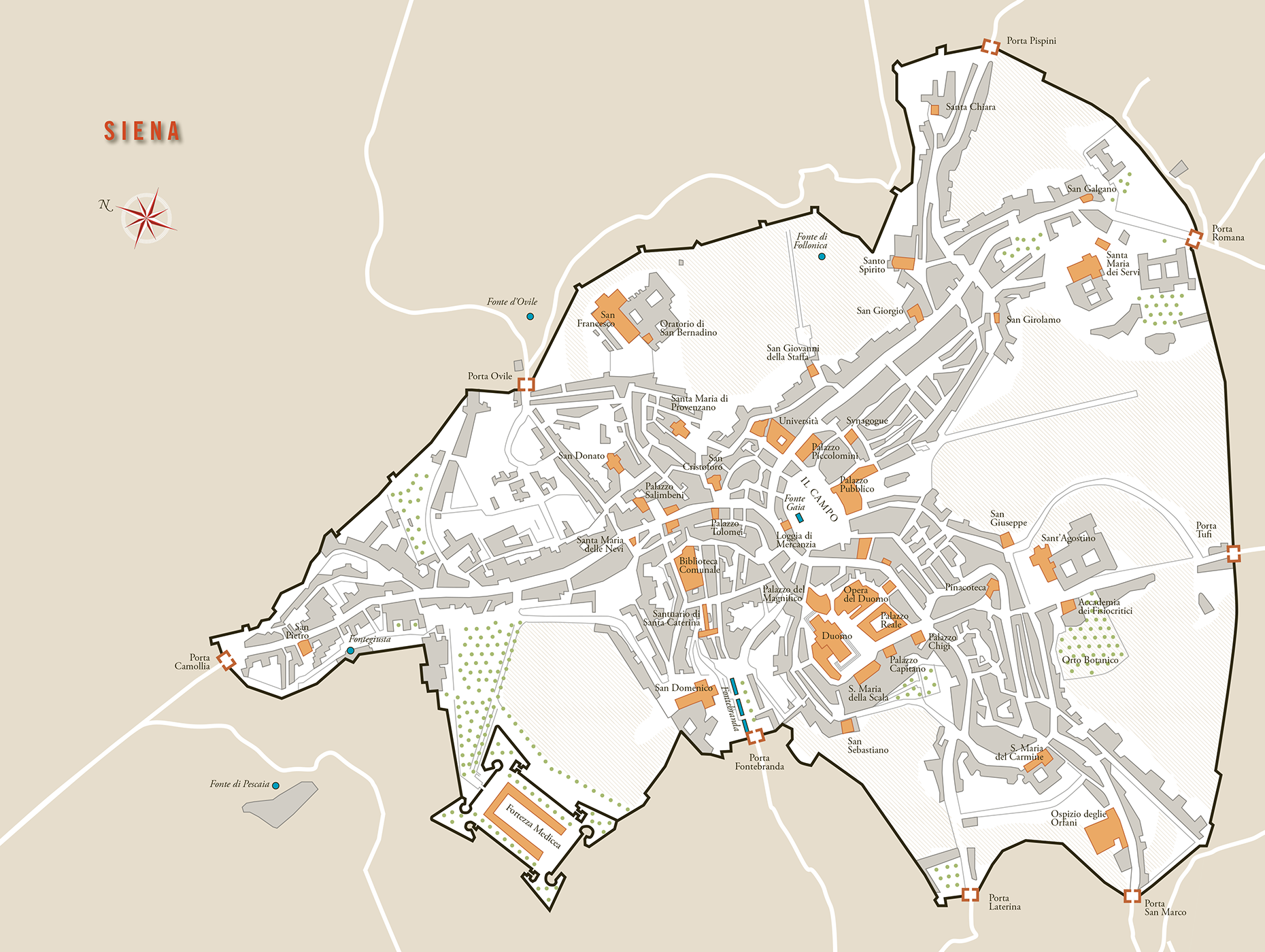

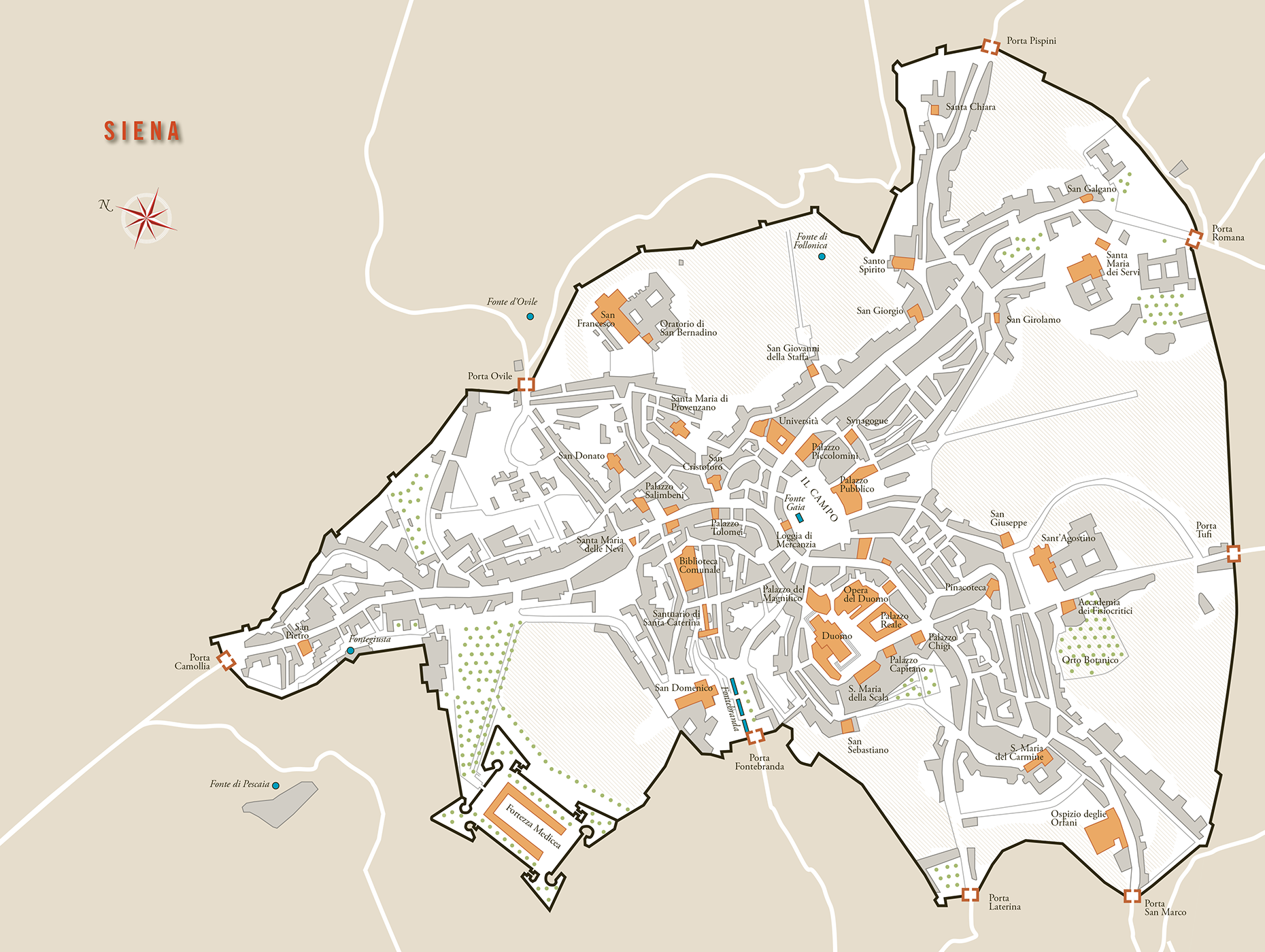

Maps by Isambard Thomas

Colour separation by DawkinsColour

Head of Zeus Ltd

First Floor East

58 Hardwick Street

London EC1R 4RG

WWW . HEADOFZEUS . COM

For Mark and Shamsu,

with much love

The ceiling of the Piccolomini Library in the Duomo

Steve Speller / Alamy Stock Photo

CONTENTS

1

G EOGRAPHY AND PREHISTORY

2

E ARLY C HRISTIAN S IENA

3

N EW B EGINNINGS

4

S IENA , C ITY OF THE V IRGIN

5

T HE D EVELOPMENT OF THE C OUNTRYSIDE

6

T HE M AKING OF THE C ITY

7

T HE D UOMO

8

E ARLY S IENESE A RT

9

T HE B LACK D EATH AND AFTER

10

S IENESE S AINTS AND H ERETICS

11

P IUS II AND THE R ENAISSANCE IN S IENA

12

P ANDOLFO THE M AGNIFICENT AND H IGH R ENAISSANCE S IENA

13

S IENESE A RT : T HE R ENAISSANCE AND A FTER

14

T HE F ALL OF THE R EPUBLIC

15

M EDICI R ULE

16

T HE P ALIO

17

T HE C ITY AND A RCADIA

18

A V ERY G REAT S IMPLICITY

19

S ENA V ETUS

Maps Isambard Thomas

Maps Isambard Thomas

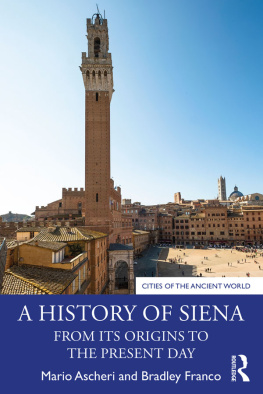

Siena is one of the best loved cities in Italy, in Europe, in the world. It offers a vision of medieval civic perfection: narrow, enfolding brick streets curving along airy hillsides, all leading in the end to the ample brick-paved slope of the Piazza del Campo, the great town square with its soaring bell tower, and the bright water of Fonte Gaia rippling sunlight up on the carved marble of its walls. This feeling of having entered a place sustained by a benign past is nourished by the absence of cars, largely kept out of the city centre, which in itself gives one the feeling of returning to a quieter, simpler world. It is a city to be explored at a walking pace; the narrow streets lined with tall brick houses provoke surprise and discovery; emerging into a sunlit square, with a neighbourhood restaurant adorned with pots of geraniums and basil, and a decorative ceramic panel with the symbol of one of the seventeen contrade (districts or wards) on the wall at the corner. Or you come upon a church you never remember seeing before, like the breathtaking glimpse of Santa Maria in Provenzano seen down the narrow slope of the Via Lucherini, baroque stone and sunlight at the end of the shadowy street. Siena is a wonderful place to get slightly lost in.

The Miracle at the Pool of Bethesda by Sebastiano Conca (1731), behind Vecchiettas Risen Christ (1476) in Santissima Annunziata.

Sailko, Wikimedia Commons

Although the overwhelming impression which any visitor receives is of an astonishing concentration of art and architecture from the late Middle Ages, there are also subtle survivors from the Renaissance, Baroque and Romantic eras. Few who have come upon them will forget the sense of personal discovery which accompanied, for example, the realization that the four statues on the Renaissance triumphal arch which frames the altar of the Piccolomini Chapel in the cathedral are little-known early works of Michelangelo. Or that one of Pinturicchios scenes in the Piccolomini Library attached to the cathedral shows an enchantingly Italianized and idealized imagining of the king of Scotland enthroned in a loggia on the shores of the Firth of Forth. Or that one of the most complete baroque theatres in Europe is concealed within the venerable structure of the Palazzo Pubblico; or that the church of the Santissima Annunciata in the great Hospital of Santa Maria della Scala has an east wall frescoed with Christ at the pool of Bethesda, the entire fresco a virtuoso exercise in perspective and illusion, a towering vision of great colonnades and sunny hillside temples. And as the Via Enea Silvio Piccolomini approaches the Porta Romana, there are the sphinx-topped gate piers of a shadowy villa garden, and an exquisite neoclassical gazebo or summer house is perched on the boundary wall.

Monteriggioni: built by the Sienese as a defence against Florence, encircled by its thirteenth-century walls and towers.

Gagliardi Photography, Shutterstock

In Siena none of the streets are straight because their gently unpredictable curves reflect the topography of the hills on which they are built. Secure between high walls of warm, pale brick, you lose sight of where you have come from without quite being able to see where you are going. But Siena is small, and you can be fairly sure that after another few steps, a slice of the Campo will appear, or the black and white flank of the cathedral, or the great, gaunt bulk of San Domenico will show up on the horizon, so that, once again, you are oriented. As Hisham Matar observes, Siena is as intimate as a locket you could wear around your neck, and yet as complex as a maze.

The historic centre predominantly consists of brick and stone, a place of warm earth tones. The houses open straight onto the street: Siena is not a place for private gardens, though there is plenty of green space and trees inside the walls. This is one of the most haunting and lovely aspects of Sienas townscape: the intense urbanity of the Campo is barely ten minutes walk from the Valle di Follonica, one of the peninsulas of country which extends almost into the heart of the city. Climb almost any street away from the Campo, and it will curve up to one of the citys three hills and offer sudden vistas of undulating countryside lying open under the sky. Looking out from the piazza in front of San Francesco, or coming to any of the brick-built city gates with their fragments of precious fresco under the arch, a fruitful and lovely countryside stretches away to the distant blue ridges of the hills. It is decorated with rows of cypresses and dotted with olive trees, neat rows of vines and patches of woodland, a vision of nature which, like the city itself, represents a vision from the past successfully brought forward into the present. This fruitful serenity, eloquent of olive oil, wine and country bread, enfolds the walls and towers of the city. Since the fourteenth century, Sienas prosperity has depended on its countryside and it is fitting that the two are so intimately related visually. There are only a handful of cities in Europe where the intertwining of town and country is so simply beautiful, and so mutually sustaining.