Bridgeman Images.

dvoevnore/Shutterstock.

Isambard Thomas, Corvo.

Isambard Thomas, Corvo.

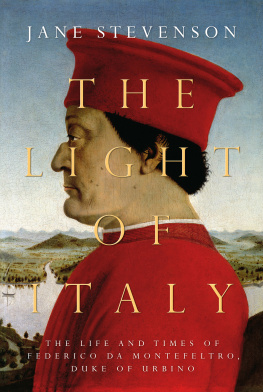

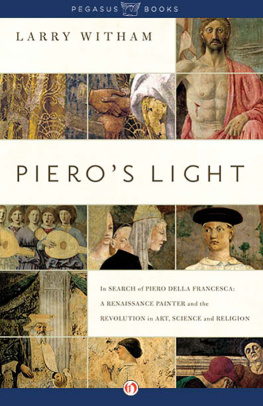

There are few paintings more famous than Piero della Francescas double portrait of Battista and Federico da Montefeltro. Facing one another in profile, their presentation suggests a pair of coin portraits: the reference to the antique that is so characteristic of the Renaissance. Battista is portrayed as a woman in her twenties, with the waxen pallor admired in her time; she is festooned with jewels, her golden hair is elaborately dressed, and her expression is neutral. Federicos image shows a man in his fifties, lips thoughtfully pursed, with sagging jowls. On his jaw is the scar of an abscess, which nearly killed him when he was eleven. In contrast to the idealized image of his wife, his portrait has something of the unflinching realism of ancient Roman funerary sculpture. Also, in contrast to his wifes brocade and jewels, he is plainly dressed in scarlet. But though his garb is plain, it is made of very costly cloth: kermes, the dye from which scarlet was made, was fabulously expensive.

Duke and Duchess preside over an ideal landscape: Piero della Francescas double portrait of Federico and Battista, his second wife.

Bridgeman Images.

The painting is not exactly lying, but it is certainly being economical with the truth. When it was painted, Battista was dead, aged only twenty-six, her tiny body worn out by as many as ten pregnancies in twelve years of marriage. In life, she was diminutive, and her complexion was sanguine. That means there was colour in her face, and she lost her temper easily, though she cooled just as quickly. She also wasnt blonde; her hair was chestnut brown. She was clever, she was an eager student of the classics, Greek as well as Latin, and she spoke up for herself. Piero della Francescas image is not a portrait of a living woman, it is a picture of how her husband wanted her remembered. And Federico, as he appears here? He looks every inch Pater patriae , the father of his country, and, as an admiring observer of the Urbino court, Baldassare Castiglione, called him, the light of Italy: la luce dellItalia . His is one of the most curated images in the history of the world. One immediate truth the painter conceals is that the duke is in profile not merely to evoke antique coinage, but because his right eye was missing, lost in a tournament when he was twenty-eight. Due to this disfigurement, he was almost never depicted full-face, and consequently there are no sculptural representations of him made in his own time. But there are dozens of images of this mild, fatherly profile: he often appears in the manuscripts he commissioned for his famous library, and he is also represented in a number of full-sized paintings and relief sculptures.

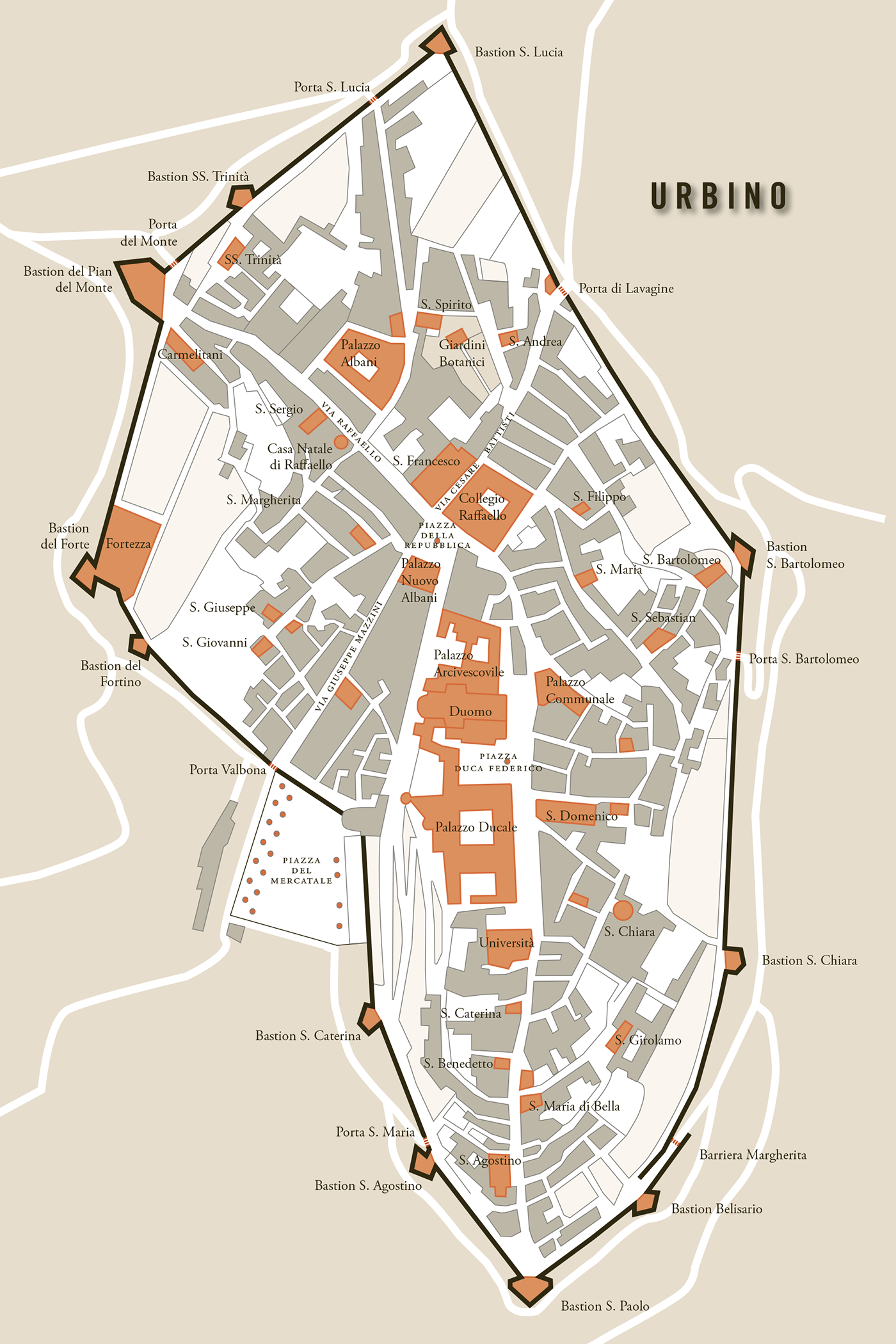

Urbino was indelibly fixed in the minds of a generation as the quintessential Renaissance city by episode four of Sir Kenneth Clarks BBC TV documentary series Civilisation , first aired in 1969. Urbino is such a sweet place so compact, so humane as for the palace of Urbino, it is the most ravishing interior in the world, he wrote from Italy to his close friend Janet Stone while he was working on his Renaissance episode, Man, the measure of all things. In the programme itself, he observes that life in the court of Urbino was one of the high benchmarks of Western civilisation. Florence, he thought, was the intellectual centre of the Renaissance, but Urbino, the ultimate expression of its ideals. He devotes a great deal of the programme to the spacious, dignified rooms of Federico da Montefeltros palace, but also includes enchanting long vistas of the timeless order of the surrounding country, with its dusty white farmhouses and dark cypresses on disciplined, terraced hillsides, and the blue Apennines rising up in the distance, the landscapes of Bellini and Giorgione.

Fifty years later, Urbino is still an idyllic hill town of steep streets lined with houses and palazzi of weathered brick. The life of the city is dominated by a large modern university, which has been inserted behind the faades of some of these structures with rare architectural tact: students make up a substantial sector of the population. Because it has been brought into the modern world with such sensitivity and loving care, it has the air of a Renaissance time capsule. It remains little visited by tourists and art lovers, partly because it is only accessible by car or bus. Only determined art lovers and the discerning take the trouble, so for many of its visitors it feels like a private discovery.

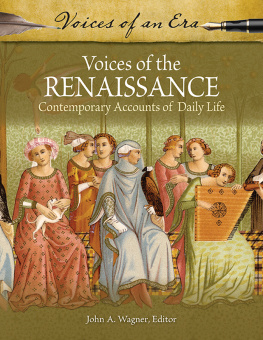

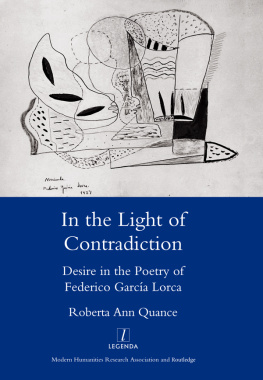

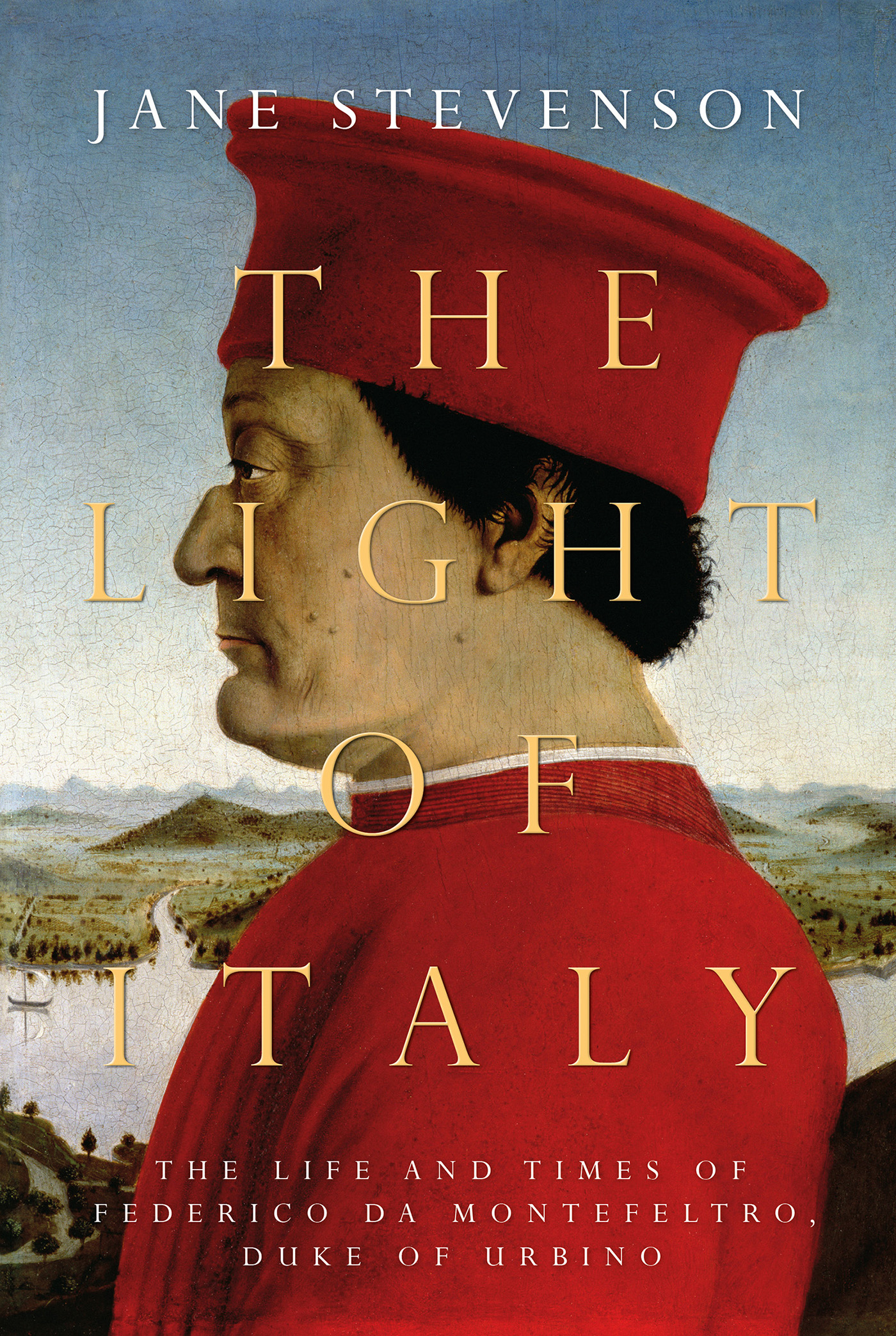

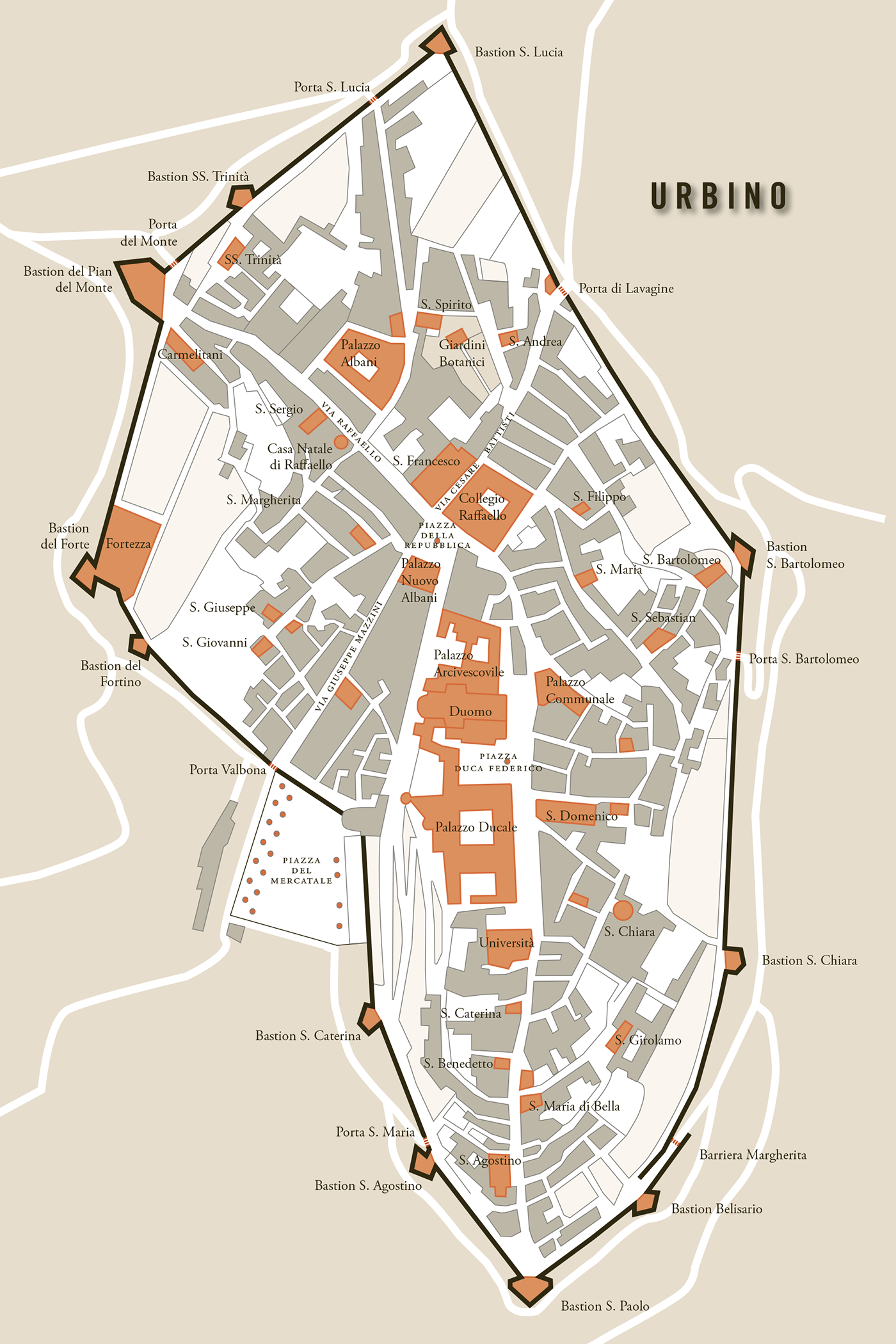

Federico reading, with the young Guidobaldo by his side, probably by Joos van Wassenhove.

Raffaello Bencini/Bridgeman.

The image of Duke Federico is central to any exploration of Urbino: the humanist warrior; the man who kept his promises in a faithless age; the Christian prince. Throughout the city, and his palace in particular, we are confronted by his personality. We see his values, his concerns, set forth in the art he commissioned. In the exquisite intarsia panels of his studiolo , copies of Cicero and Seneca lie piled up in fictive cupboards accompanied by musical instruments, and his Garter hangs casually from a hook. In another portrait hung in the studiolo , probably by Joos van Wassenhove, he sits rather stiffly upright, reading Gregory the Greats Moralia in Job , wearing full armour under his ducal robes, with his Garter buckled round his calf, and the insignia of the Order of the Ermine on his shoulders. He is accompanied by his little son, Guidobaldo.