Preface

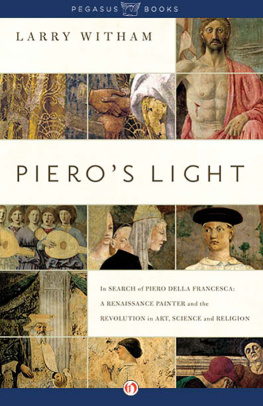

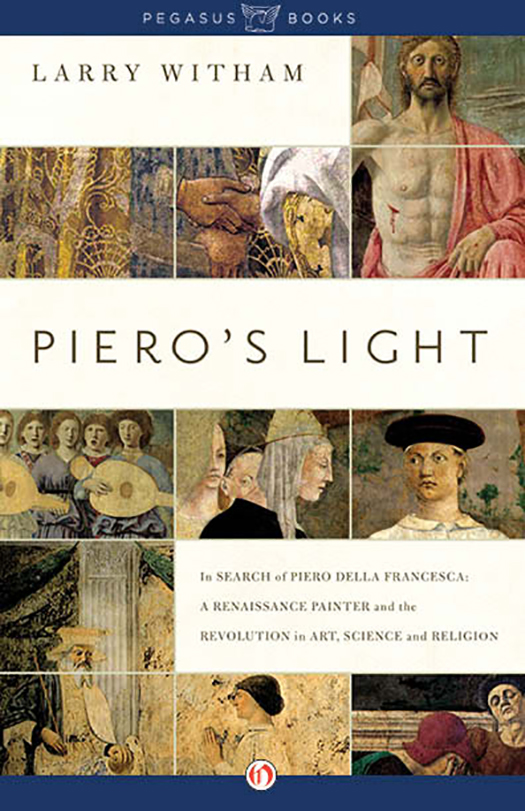

P iero della Francesca first crossed my path when I was a college art student in the early 1970s. Like a Michelangelo, Raphael, or Leonardo, Piero was presented on a first-name basis. He was clearly not as famous as the big three. Among the Renaissance painters, though, Piero stood apart. His imagery looked strangely ancient and modern at the same time. More recently, Piero attracted my attention once again. After two decades of writing on the topics of religion, science, and philosophy, it occurred to me that the life of Piero offers a window on a broader topic: the roles of art, religion, and science in how we perceive the world.

Transcending his time in history, Pieros legacy allows us to understand the precipitous change in art, religion, and science that began to take place during the Renaissance and has affected the Western world ever since.

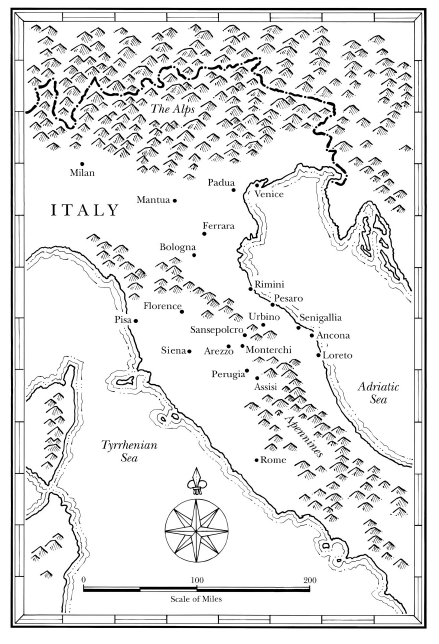

Pieros story begins in the early Quattrocento, the 1400s on the Italian peninsula. It was a time when there actually was no modern Italy, but rather a mosaic of city-states, from Florence and Milan to Venice, Perugia, and Rome. In Pieros day, many of the barriers we have now erected between art, religion, and science did not exist. This was the so-called medieval synthesis, and Piero was its product. He was in the artistic stream of the late medieval craftsman: a painter of religious topics and an innovator in mathematics and geometry. In his lifetime, the synthesis of the Middle Ages was being added to by the Renaissances revival of the classical past: the arts and letters of Greece and Rome. Art returned to an imitation of nature. Religion revived Platonist thought. And in science, there was a growing fascination with mathematics, optics, linear perspective, and the physical structure of the heavens.

On the whole, Piero della Francesca is a figure who represents a kind of integration of the aesthetic, spiritual, and intellectual aspects of human life during his time in history. He was part of a cultural consolidation that perhaps was uniquely achieved in the late Middle Ages as a prelude to the Renaissance, and it is one that, in the modern world, we are still very interested in experiencing. For people of the Middle Ages, Life appeared to them as something wholly integrated, the Italian historian Umberto Eco says in his essay Art and Beauty in the Middle Ages . Nowadays, perhaps, it may even be possible to recover the positive aspects of their vision, especially as the need for integration in human life is a central preoccupation in contemporary philosophy.

The story of Piero allows us to explore this bygone vision and see its continuing relevance. To assist in that goal, a second theme of this book will be that one of the revivals of the Italian Renaissancenamely, the philosophy of Platonismhad provided an integrating framework for Piero and others. Piero lived and worked within a Christian Platonist tradition that was maturing during the Italian Renaissance. It was an intellectual subculture that was attempting to reconcile Greek philosophy and science with Christian belief. He was introduced to the Platonist revival by the religious movements and humanist scholars around him, and, while not university-trained, Piero had ample opportunity to absorb the new thinking. In his own right, he edited, transcribed, or illustrated at least eight physical manuscripts on mathematical topics, some of which reflected the Platonist interest in ideal shapes and numerical proportions.

Although the Platonic dialogues explain how difficult, even impossible, it is to perfectly apprehend either the physical or transcendent worlds, Platonism presents both pursuits as worthwhile and basic to human life. The transcendent world offers ideals or essences that are deemed worthy of contemplation and explication. In turn, the physical world is in constant flux, vast and elusive and yet knowable by a process of critical thinking and reflective experience. And as Platonists have consistently argued, this world of flux mysteriously yields to the power of mathematics.

Piero was not the originator of such mathematical concerns during this transition from the Middle Ages through the Renaissance, but he applied mathematics to his art, innovated in arithmetic and geometry, and wrote extensively on these topics. The mathematical features of Platonist thought would eventually contribute to the Scientific Revolution, and Piero was an important benchmark on the way there. Going further, it could be argued that even the artistic innovations of the Italian Renaissance helped shape a new scientific view of the world.

Platonism is not the only big idea that emerged from the Renaissance. That period in history perpetuated a number of philosophies that are still with us: individualism, humanism, skepticism, Epicureanism, scientism, political cynicism, the occultism of the perennial New Age, and certainly the striving for fame, wealth, and glory. Yet amid these many streams of thought, Platonism has proved to have much broader implications about the nature of reality and human perception, and thus an enduring ability to integrate the ideas of visual beauty, spiritual or mental transcendentalism, and scientific progress. Accordingly, the second part of this book, which follows Pieros legacy down to the present, will also explore the Platonist legacy.

The jury is still out on the nature of the Italian Renaissance itself, too, surprisingly enough, and this further complicates any story about Piero and his significance in history. Some historians view the Renaissance as no more than an extension of the late medieval world, rejecting the idea that it was the chief moment of European rebirth. Even more skeptical of its existence, other historians have called the Italian Renaissance a fiction created by later generations, a kind of romantic hindsight. In making this claim, Burckhardt was astute enough to acknowledge that he was presenting a very personal picture of the Renaissance based on his own modes of research and analysis.

This book shares Burckhardts basic confession that any broad interpretation of a trend in human history and thought must be simply a picture for readers to consider, nothing more. When it comes to Pieros life in particular, many approaches could be taken.

Despite Pieros elusive presence in history, it is a testimony to his acclaim that his story has extended far beyond his lifetime: this has been called the search for Piero. Following his death, his memory was briefly chronicled. Then he was virtually forgotten until the nineteenth century, when there was a kind of Piero revival in Europe, bringing him to the attention of the English-speaking world. The universal quality of Piero was recognized again in the twentieth century. This was the century not only of modern art, which in itself put a new lens on Piero, but of the era when physics and biology provided a firm foundation for the mechanistic sciences. These included neuroscience, and thus a final challenge to belief in the transcendent Platonist ideals of the Renaissance.